Set up to be safe havens, some group homes for the disabled have become remote "prisons," where residents are vulnerable to violence and neglect.

Late one night this summer, George Daly woke abruptly to the sound of the fax machine humming from the den of his tidy home near Minneapolis.

It brought tragic news: Just hours earlier, on a desolate stretch of highway in northern Minnesota, Daly's granddaughter, Ashley, had slashed her wrist with a piece of glass and thrown herself in front of a speeding car.

It was the seventh suicide attempt since Ashley, who has bipolar disorder and a cognitive impairment, was sent to live in a group home three hours away, on the wooded outskirts of Hermantown, Minn.

"Ashley feels lost and abandoned," said Daly, who settled on the facility only after several others closer to the Twin Cities turned them down. "She has no place to call home in this world and this is her way of crying out for help."

Each year, hundreds of Minnesotans with developmental disabilities and mental illnesses are uprooted from their families and sent to live in secluded group homes in remote parts of the state. Cut off from the communities they know, housed with strangers, they often fall deeper into anger and despair. Many, like Ashley, see violence and self-injury as their only means of escape.

Minnesota's far-flung network of group homes is another sign of how it has fallen behind other states in the movement to integrate people with disabilities into mainstream life. Though designed as safe havens for people too vulnerable to care for themselves, group homes now leave thousands of adults isolated and vulnerable to neglect and abuse.

A Star Tribune review of hundreds of public documents has found:

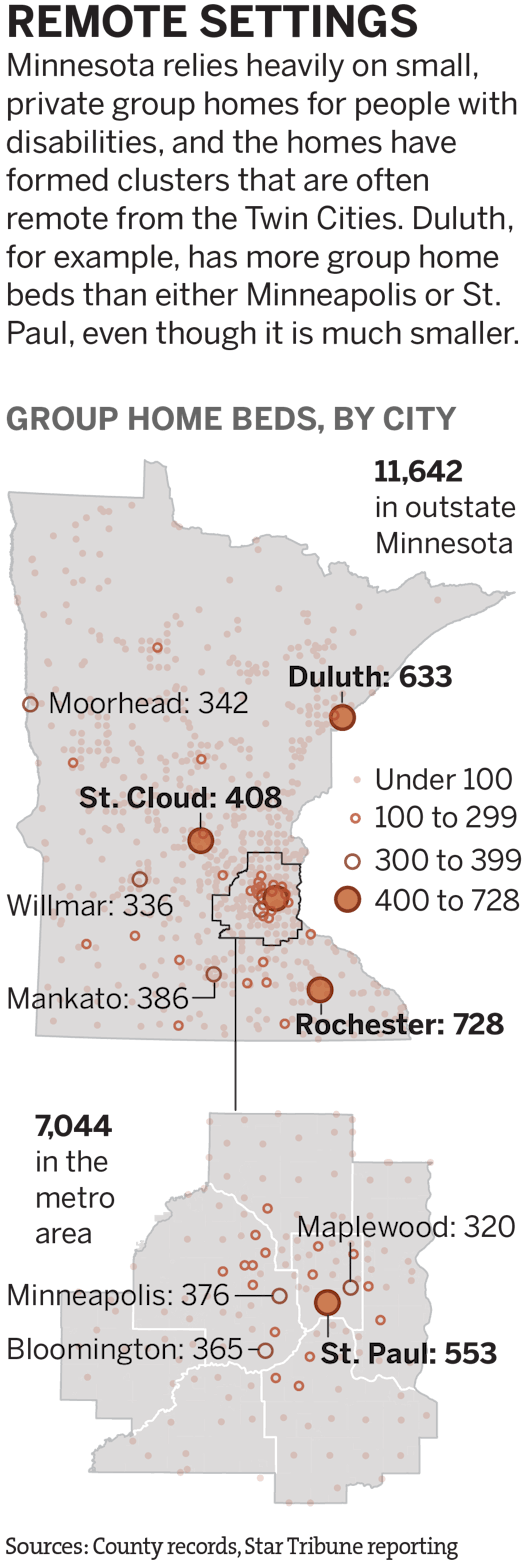

• Minnesota relies more than any other state on group homes to house adults with disabilities, spending $1 billion annually for about 19,000 people in more than 4,500 facilities.

• While many group homes are safe and orderly, others are understaffed and chaotic. Each year, state regulators receive more than 700 reports of abuse, neglect, exploitation and serious injury at Minnesota group homes. In 2013, a federal judge became so alarmed at conditions facing group home residents that he appointed a special monitor to review their care.

• Scores of Minnesota's group homes lie in remote rural settings, placing residents hours away from relatives who might assist with their care and check on their well-being. The Star Tribune analyzed records for more than 5,000 individuals and found that one-third were placed in group homes outside their home counties. Of these, hundreds live more than 100 miles from their home counties, often in small towns such as Hermantown in rural St. Louis County.

• In dozens of interviews, people with intellectual and developmental disabilities said they were sent to group homes against their will, even when they were capable of taking care of themselves.

"This feels like a prison," said Joshua Burt, 28, standing outside the Rochester group home where he was placed, against his wishes, six years ago. "This is not the place for me, but it feels like my life is outside of my hands."

Erin Metzger, director of outpatient mental health at St. Luke's Hospital in Duluth, said she has seen dozens of patients cycle through local psychiatric wards and clinics after they ran away from group homes.

"My heart breaks for these people," she said. "They're hundreds of miles away from their families and support systems, and that makes them sicker."

In September, under pressure from U.S. District Judge Donovan Frank, Minnesota completed a plan that would give people with disabilities more say in where they live and raise the number living independently. But the increases are modest, and the plan does not call for closing group homes or reducing their state payments.

'Woods and swamps'

Remote settings such as Hermantown not only place group home residents far from family and friends, they can contribute to neglect and violence.

In 2010, a 44-year-old man with schizophrenia went missing after wandering away from his group home north of Duluth. A group of deer hunters discovered his bones two years later, decomposing inside his clothing in the woods.

"People like to say these homes are in the 'community,' " said St. Louis County undersheriff David Phillips, as he drove by the woods where the man's remains were found. "But about the only community out here is woods and swamps."

In Lewiston, a man with schizophrenia and a degenerative brain disease died after falling seven times in the kitchen of his group home. Despite sustained bruising and four cuts on his head, staff members said the 58-year-old man fell "for attention" and did not call for medical help, state investigators found.

In a case last year, a 26-year-old man living at a group home in Princeton, Minn., was found dead on his bedroom floor after staff had lost contact with him for more than 44 hours.

In some cases, residents simply run away, hoping that someone will move them if police take notice. VaLinda Henry suspects that's what drove her son, Troy Henry, 41, who was cognitively disabled and had schizophrenia, to wander off into the forest near Stillwater with a plastic bucket full of his personal belongings. Later that night, his body was found floating down the St. Croix River, with the bucket attached to his waist. Sheriff's deputies found what appeared to be the words "MY WILL" scrawled in the sand nearby.

Just days earlier, Henry had called his mother, saying the group home wouldn't let him leave for a weekend with his two children, ages 13 and 15. "They treated my son like a prisoner," his mother said, sobbing.

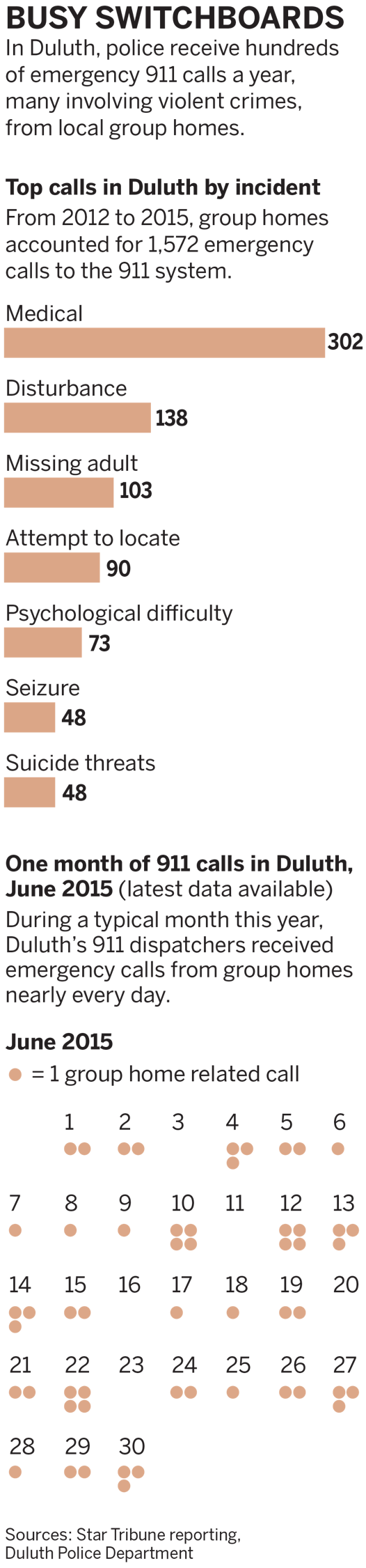

In far northern Minnesota, the consequences of isolation have reached crisis levels. Stuck for months or years, often among housemates with severe mental illnesses, many residents lash out at each other, turning these homes into small battlegrounds, according to county health officials and group home workers.

"It's not right for human beings to live this way," said Cody Jakowski, a crisis responder at Stepping Stones for Living, a company that operates group homes near Duluth. "People aren't meant to be isolated like this."

In St. Louis County, more than one out of every three 911 calls involve incidents at group homes, the sheriff's office estimates.

"What is happening up here is brutal beyond belief," Phillips said. "It's like hundreds of little train wrecks dotting our landscape."

Remote clusters

Minnesota's reliance on group homes dates to the late 1970s, when it led the nation in shutting down large state hospitals that housed people with mental illnesses and developmental disabilities. The state encouraged small, private group homes as a more humane and cost-effective alternative, and subsidized them through Medicaid and other programs.

Many of these early group homes sprouted up near the shuttered state hospitals, in outstate cities such as Faribault and Rochester. Soon, large for-profit operators began clustering group homes nearby, in rural areas where land was cheap and local resistance was minimal. Today, 62 percent of Minnesota's group homes are outside the Twin Cities metro area, state data show.

The biggest cluster is in St. Louis County, where half the group home residents come from other parts of the state. Some local officials now refer to their county as the "State Hospital of Duluth."

The result, some advocates say, is a system with the same misguided paternalism that "separate but equal" embodied during the civil rights movement a half century ago.

"It's a segregated system," said Mark Nelson, division director of adult services in St. Louis County. "If you concentrated this many people of color in one area, there would be accusations of discrimination."

Once this far-flung network emerged, it became self-perpetuating. County social workers typically recommended group homes as the only option, even for people with moderate cognitive problems, even in communities with services to support independent living.

And though group homes were meant for people needing 24-hour care, such as patients with severe mental illnesses, many accept just about anyone with an intellectual or developmental disability. Records show that even clients who need just basic assistance with daily activities — like cooking meals or catching the bus — can wind up in group homes that cost up to $80,000 per person per year.

"We are spending hundreds of millions of dollars a year for 24/7 care for people who don't want it and don't need it," said Nancy Fitzsimons, a professor of social work at Minnesota State University in Mankato. "Minnesota fell in love with the four-bedroom group home model, and we got stuck."

Top state administrators and group home industry leaders acknowledged that many people who could be living independently are instead steered toward group homes. Clients are now being asked where they want to live, a process the state plans to complete by the end of 2016.

"There are people living in group homes who probably could live in other settings, but either don't know the options or don't trust the options,'' said Alex Bartolic, disability services director at the state Department of Human Services. "Everything has to change — our context and our way of coming at this.''

'SET UP TO FAIL'

Tony peered nervously from behind the plastic blinds of his one-room apartment. He could hear a police siren in the distance, then some loud shouting, then a heavy silence.

"I wish I lived far, far away from this ..." he paused, searching for the right word, "sewer."

Read full story'Most people get to choose'

Every so often, Joshua Burt stares out the basement window of his Rochester group home and imagines an elaborate escape. Burt sees himself packing a suitcase and then waiting for a rare moment, usually a Sunday afternoon, when shift changes sometimes leave him unsupervised. He imagines running to a nearby bus stop, using the neighborhood trees and bushes as cover.

"I think about escaping two or three times a day," said Burt. "But where would I go?"

Burt, who has a mild developmental disability, was never asked whether he wanted to live in a group home. The decision came, he said, on the day he and his siblings learned that their mother had lung cancer.

"My brother came up to me and said, 'Mom wanted you in a group home,' and that was it," he recalled. Weeks later, Burt was told to pack his belongings from his mother's trailer in a mobile home park outside Rochester, then was taken to a group home he had never seen, to live with three strangers.

"It seemed unfair," said Burt. "Most people at least get to visit the places where they live and choose who they get to live with."

Burt works two part-time jobs — at a Wal-Mart and a Culver's restaurant — and aspires to get his own apartment. Then he wouldn't have to ask permission to have visitors or go on fishing trips with co-workers. But Burt gets just one chance a year to make his case, at a meeting that includes his county case worker, group home provider, and his older sister, who is also his guardian.

At this year's meeting, Burt said, he was told he still lacked adequate "financial management skills."

"I keep saying, 'I want out,' but no one listens," Burt said, after wrapping up a shift at Culver's. "How is it possible that I can work two jobs and take the bus here every day, but can't live on my own?"

A pattern of scars

No one ever asked Ashley Daly either.

When her grandparents, who adopted her as an infant, decided they had grown too frail to handle Ashley's violent mood swings, they asked for help from the county. A social worker gave them a long printout of group homes, most located far away, that might accept Ashley.

With little more than Google to guide them, George and Ruth Daly worked their way through the list. George asked each provider a series of 10 questions — "Do you have locked doors?" and "Do you involve them in the community?" — and jotted down plus or minus signs next to each one.

The group homes with the most plus signs were typically in remote places, like Saginaw and Thief River Falls. Many had wait times of a year or more for a bed.

When a provider from northern Minnesota finally called them with an opening, the Dalys were elated. Though it was a long way away, the couple hoped the remote location would keep their granddaughter safe. "You wouldn't run away, because you wouldn't know what direction to run," George said.

A year later, the Dalys admit they underestimated Ashley's attachment to her family and childhood home. It was only after arriving in Hermantown that she began her suicide attempts, each one prompting a faxed report to her grandparents. More than a dozen deep, zigzagging scars line her forearms, marking the many times she has cut herself since arriving up north.

On a recent morning, she staggered from her bedroom at the group home, spread out on a couch, and described how much she misses her grandparents' house and her pet terrier, Holly, who stayed behind.

"I had a dream last night that I finally got to see Holly,'' she said. "Why has everyone abandoned me?"

On long distance calls home, Ashley would ask her grandparents, "Why did you adopt me if you couldn't even finish the job?"

The question hangs heavy over the Dalys, who now wonder whether they made a mistake by sending her so far away. They even considered shipping all her bedroom furniture up north to make her feel more at home. But, like thousands of other Minnesota families, they were beginners in a baffling system that seemed to offer no middle ground between keeping Ashley at home and sending her far away.

"We did our very best with the options we had," Ruth Daly said, "and no one to help us."

'I became lost'

On the long drive back from the North Woods, Ashley Daly hummed the words to her favorite song, "Put Your Records On," from the back seat of her grandparents' sport-utility vehicle. Ashley's voice got louder and more animated as the family neared the suburban landscape of her youth — the day care center and the playground where she once walked her dog now spread out asleep on her lap.

After a long, cold winter in Hermantown, in a group home that allowed her only 20 minutes of "alone time" each day, Ashley was brimming with excitement at spending Easter weekend with her grandparents in Minnetrista. George and Ruth have kept Ashley's bedroom exactly as she left it — walls painted with pink butterflies and windowsills lined with teddy bears. On the living room couch is the extra-thick security blanket that George and Ruth would gently wrap around Ashley when she would fly into one of her "rages" and needed to calm down.

"Grandpa!" Ashley called out from the back seat. "Tonight, after we get home, can we watch the stars? Like we did when I was little?"

"Honey, we told you this before," George Daly said, as he pulled into his neighborhood. "This is NOT your home. Your home is in Duluth."

But attempts to make Ashley feel at home up north have not worked. In late July, she moved to a new group home in Duluth after the one in Hermantown determined it lacked adequate staffing to keep her safe. The new home is in a residential neighborhood, but Ashley said she's still lonely — she still misses Holly and staying up late watching episodes of "CSI" with her grandpa.

Beneath Ashley's bed is a box full of the poems and essays she has written since middle school. Many reflect her sense of abandonment, including self-portraits showing her lying in a pool of blood or hanging from a noose. Among the assorted letters is one she wrote to herself on the October night her grandparents first dropped her off up north.

"I became lost once I learned I was moving to Duluth," Ashley said, reading the letter. "I lost everything. Trust. Hope. Relationships. Friends. Family. … I felt this was the end."

Ashley leaned her forehead on the dining room table, exasperated, and added, "I just want to go home."