Since 2012, this county alone has prosecuted nearly 2,000 people for felonies against senior citizens — far more than Minnesota and most other states.

In addition to bringing criminals to justice, the county's tactics prevent hundreds of other elder crimes that might occur in the absence of high-profile enforcement, said Greenwood, head of San Diego County's elder abuse unit.

"No other county in the nation has such an aggressive, all-hands-on-deck response to elder crimes," said Julie Schoen, deputy director of the National Center on Elder Abuse. "Others wish they could replicate the model, but so far San Diego is unique."

A warm August breeze rustled the palm trees outside a senior care home tucked amid the foothills east of San Diego as Greenwood straightened his tie and approached one of the units. He knocked on a door with peeling paint and a sign reading, "Dreams Do Come True."

The door opened, and through a crack an elderly woman's overjoyed face emerged.

"Oh God, oh God!" she said. "You won't believe what has happened to us."

Joanne Rogers, 80, and her husband, Stan, 76, were desperate. They told Greenwood that their assisted-living facility had drained every last dollar from their bank account, and they suspected their son was angling to take even more. They had run out of toothpaste, shaving cream, fresh food and other essentials. Joanne pulled up her pants leg to reveal a festering rash. The couple could not even afford bus fare to the nearest pharmacy or medical clinic.

With no relatives nearby to help, the Rogerses had called Greenwood's elder abuse unit as a last resort. "We never thought we would need your representation," said Stan Rogers, a retired truck driver who now uses a wheelchair. "But this is what our world has come to."

Minutes later, Greenwood was charging down the facility's narrow halls, looking for an administrator and answers. He soon emerged from a corner office with a packet of billing statements in his hand. The records showed that the Rogerses were paying $5,200 a month for their cramped unit — a one-room apartment with a single window overlooking a dusty courtyard.

Back in the couple's living room, Greenwood peppered them with questions. Were they actually getting the twice-a-day nursing care listed in their monthly bill? Did they know their expenses had shot up 40 percent in just a few months? And who had authorized these payments?

Gradually, the couple realized they were broke because they were paying for services they had never approved and were not receiving.

"God almighty!" yelled Stan Rogers, pumping his fist in the air. "You've got our permission to get to the bottom of this. We trust you, brother."

Such an encounter seldom happens in Minnesota, or in most counties across the nation, because state health inspectors and criminal prosecutors mostly confine their work to the office or the courtroom.

In San Diego County, members of the elder abuse unit make hundreds of house calls a year — often dropping in unannounced on mobile home parks and nursing homes. Most of the visits result in no criminal charges, but they put the county's 795 senior care facilities on notice that trained investigators are monitoring them and are prepared to pursue criminal charges if problems go unfixed, officials said.

As a further line of attack, the San Diego Police Department deploys more than 400 volunteer officers who make regular checks on thousands of isolated seniors in their homes and facilities. The volunteer officers, all retirees, wear police-like uniforms and roam the neighborhoods in retired squad cars, visiting seniors who live alone or have requested extra surveillance. When the volunteers see evidence of abuse, they call Greenwood's office.

"The facilities around here, they know we're watching," Greenwood said, as he cruised down a wide boulevard lined with eucalyptus trees. "We get around."

The house calls are among many unorthodox methods that Greenwood's team uses to maximize prosecutions of crimes against seniors. Recognizing that older victims often fear testifying in court, Greenwood's staff takes pains to prepare them for the stress of the witness stand. Their 12th-floor office overlooking the San Diego Bay is outfitted with wheelchairs, walkers and oxygen machines. The unit also has a special witness room — with sofa, flowers and soft lighting — where elderly victims can await their hearings, usually with victim advocates at their side.

Early on a recent morning, a woman arrived at the unit, her hands shaking visibly at the prospect of testifying. Katie Wilson, an advocate trained in dealing with trauma victims, held the woman's hand, gazed into her eyes, and consoled her with words she repeats with many elderly victims:

"I'm so very sorry that you have to be here."

Gradually, the woman's hands stopped trembling as Wilson calmly walked her through the criminal justice process.

Like everyone on the unit, Wilson makes regular house calls. She makes a habit of bringing the victims flowers and home-baked meals.

"We coddle these victims because they deserve to be coddled," Wilson said. "And if we didn't give them this VIP treatment, then a lot of them would never have the courage to testify in court. It's why we are able to put so many of these terrible people behind bars."

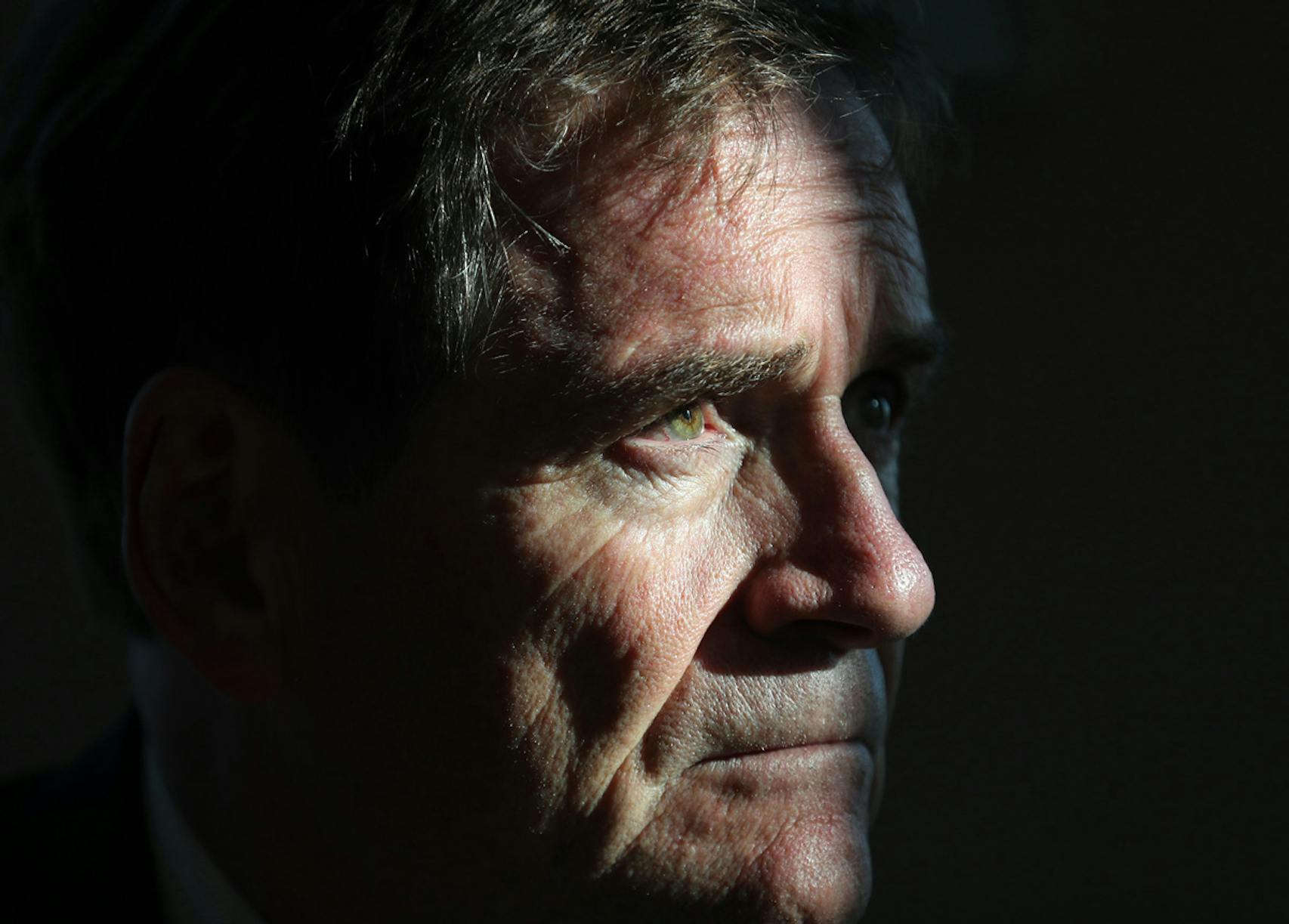

For years, Greenwood has kept to a strict morning routine.

At 6 a.m., he boils water for a pot of English tea. He scans dozens of overnight e-mails for fresh reports of abuse. Finally, tea in hand, he launches into a boisterous, long-distance video call with his 94-year-old mother, who lives alone in the house where she grew up in Crawley, a town in West Sussex, England.

As a young law school graduate in the 1970s, Greenwood was traveling through the western United States when he stopped at a Baptist church in San Diego. He struck up a conversation with the young woman sitting next to him in the pew; the two fell in love and married five years later. Greenwood spent 13 years working as a barrister and solicitor of the Supreme Court of England before his wife's worsening health forced them to move back to her hometown of San Diego. Two years later, he landed a job as a prosecutor in the San Diego District Attorney's office.

In 1996, Greenwood was summoned to the office of Paul Pfingst, then the San Diego District Attorney. Pfingst told him he would be heading up a new unit focused on elder abuse, among the first of its kind in the country.

"My initial reaction was, what is elder abuse?" Greenwood said.

He had no cases and no sources. Each day, a parade of detectives and attorneys strolled by his desk, carrying folders of domestic violence and other criminal cases. But no one stopped at his desk.

"There was a wall of silence," he said, "and silence is the biggest barrier to successful prosecutions."

Greenwood quickly built relationships with police officers and sheriff's deputies across the county of 3.3 million people. Next, he turned his attention to another problem: the lack of coordination between state and county agencies. In California, as in many states, the Department of Social Services handled complaints about state-licensed senior facilities, but it had no power to launch criminal investigations. County prosecutors had the legal and forensic tools, but generally considered elder care homes outside their jurisdiction.

Greenwood pressed state officials repeatedly, insisting that they share abuse cases with local prosecutors.

"Initially, they viewed me as some sort of overzealous crusader," he said.

But eventually he prevailed. Greenwood's office now gets dozens of maltreatment reports a month from the state, on top of referrals from police. Since that change, Greenwood's unit has increased its felony convictions in elder abuse cases to about 330 a year.

By contrast, Minnesota convicts an average of about 70 defendants a year under its vulnerable-adult statute — about three-quarters involving financial crimes — and perhaps a few dozen more under fraud and assault laws.

San Diego's approach also eliminates the costly delays that can derail a criminal prosecution. Patrol officers with the San Diego police are trained to call the department's four elder abuse detectives within minutes after responding to an elder crime. As a result, these detectives start collecting evidence and interviewing witnesses immediately, before the victims forget crucial details.

"I want to be there before the blood dries," said Cory Gilmore, one of the four detectives. "I want to talk to the victims. I want to establish a rapport with them. And I want them to know right away that there is someone who cares."

The county's elder abuse teams were unusually busy this summer, amid a series of horrific crimes against seniors. In one case, a 60-year-old woman was beaten savagely with a baseball bat by an acquaintance wearing a devil's mask. When elder abuse detectives searched the assailant's home in August, they found handwritten notes on homicide defense strategies, as well as credit cards and bank account numbers belonging to the victim's mother. The assailant eventually pleaded guilty to attempted murder and was sentenced to more than 30 years in state prison.

"I probably go further than most prosecutors are comfortable with," Greenwood said. "But so far, it hasn't gotten me in too much trouble."

Greenwood's achievements have earned him a national reputation, and one afternoon in September, he took the podium at a convention hall north of the Twin Cities, one of more than a dozen speeches he gives each year. Many of the nearly 200 police officers and prosecutors in the audience had come just to see him and learn his techniques. He spoke for more than two hours without notes, repeatedly denouncing the "myths" that stop prosecutors from pursuing elder abuse cases.

"The most common misperception is that elderly victims make bad witnesses," he declared. "My experience has been totally the opposite. They make terrific witnesses! I would much rather put on the witness stand a 96-year-old lady than a 21-year-old beach dude who lives in Pacific Beach who can't remember what he did yesterday."

But even in San Diego, prosecutors acknowledge that they feel overwhelmed by the volume and range of cases.

Greenwood's voice mail is generally filled to capacity with complaints and pleas for help. He insists on responding to every one, no matter how minor. On his wall is a letter from an elderly couple thanking him for calling Verizon's chief executive to resolve a dispute over a cellphone bill.

"I never say, 'Sorry, that doesn't have anything to do with me,' " Greenwood said. "It's a weakness, really. But how do you look the other way when the victim could be your own mother?"

Chris.Serres@startribune.com 612-673-4308David.Joles@startribune.com 612-673-7904