GRAND MARAIS, MINN. — He was once an American sports hero, a high-flying playmaker from Minnesota's Iron Range who competed with the best hockey players in the world.

Forty years ago this month, Mark Pavelich was thrust into the international spotlight when he passed the puck to a U.S. Olympic teammate for the game-winning goal over the powerful Soviet Union in an epic matchup forever remembered as the "Miracle on Ice." Two days later, the U.S. won gold.

But now, on a gray wintry day in the Cook County courthouse, Pavelich's glory days were a distant memory.

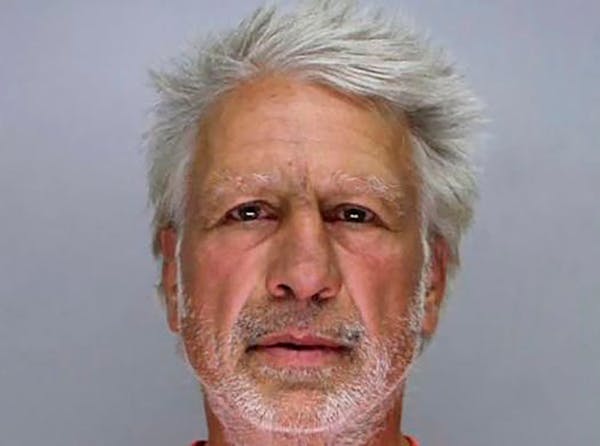

His once-thick brown hair was tousled and silver, the star-spangled uniform of the 1980 Olympic team replaced by a faded striped jailhouse jumper. Charged with beating a neighbor with a metal pole, the 61-year-old sat handcuffed before a judge as he listened to psychologists opine that he was so mentally ill he couldn't be trusted with his own safety.

It was a heartbreaking fall for his family and friends to see. This wasn't the kind, generous introvert they knew, the quiet, solitary man who wasn't apt to pick a fight. This was a Mark Pavelich they didn't recognize — someone who, in recent years, had started to act confused, paranoid and borderline threatening. And it left them wondering: Was the game that had given Pavelich so much purpose and joy through the years also destroying him?

Too many hits, too many blows to the head, too many collisions while battling for loose pucks on rinks from Eveleth to New York City have led Pavelich's family to believe he suffers from chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a degenerative disease that can manifest in violence, impulsiveness and paranoia.

This spring, months after sending Pavelich to a secure state facility for mental health treatment, a judge is expected to decide whether his condition has improved to the point where he is no longer deemed dangerous.

Pavelich, speaking by phone from the facility, said recently that he felt he shouldn't grant an interview while the determination is pending. "It's just too tricky here," he said.

In the meantime, his family is working to call attention to his plight and that of other athletes forever damaged by the games they played.

"Maybe his story is supposed to help a lot of people," said Jean Gevik, Pavelich's sister. "That's what I'm hoping."

Dedication

Mark Pavelich declared as a young boy that he was going to be an Olympian.

"It wasn't a question," Gevik said. "He was going to make it work."

Growing up in Eveleth, where hockey reigns supreme, Pavelich skated on the lake in front of his house as well as at a rink a quarter mile away. He rose before dawn to practice, and he often stayed late after other players left to work on stickhandling drills or to practice passing the puck from skate to stick. On some school nights, his parents practically had to drag him home.

A big Bobby Orr fan, he and teammate Ronn Tomassoni persuaded the manager at the U.S. Hockey Hall of Fame in Eveleth to let them watch hours of NHL highlights, both boys mesmerized by the smooth-skating Boston Bruins defenseman.

What Pavelich lacked in stature, at 5 feet 8 inches tall, he worked to make up with finesse, speed and grit. Though he didn't pick fights on the ice, friends said, he never shied away from action. "A lot of guys don't want to be the first person in the corner because you know you're going to get hit," Tomassoni said. But Pavelich "wasn't going to shy away from the physicality of the game."

Teammates saw early on that Pavelich was a cut above. "He just skated so smooth. His skates never left the ice," said Peter Gilliam, a high school teammate. "He just glided."

And yet, Gilliam and others said, Pavelich was an unselfish player, a center with a sixth sense for finding open wingers for a quick pass and a shot on goal.

"He would have an empty net after beating two defensemen … and give me the goal," Gilliam said. "People … need to know how gentle Mark was."

Pavelich's life was jolted at age 18 when he was involved in a hunting accident that killed his friend. Ricky Holgers, 15, was hit by a ricocheting bullet, his brother Mike Holgers recalled. Pavelich had pulled the trigger. He raced about a mile through the woods to call an ambulance, then ran back to help his brother carry Holgers out, Gevik said. Later, he disappeared into the forest, distraught. A search party found him curled up by a tree, covered in blood, Gevik said.

After that, nobody talked much about it, Gevik said.

"You didn't know how to deal with tragedy back then," she said. "You just kind of brushed it under the rug and hoped it went away."

Holgers' family remained friends with Pavelich. And Pavelich forged ahead.

He earned a spot on the University of Minnesota Duluth team, where he won All-America honors before going on to star for the 1980 U.S. Olympic team under coach Herb Brooks.

NHL teams later shied away from Pavelich, his small size a big factor. So he learned to fly an airplane and played guitar in a band, often covering the Rolling Stones. He played hockey in Switzerland for a while.

Then Brooks became head coach of the New York Rangers and gave Pavelich a shot at the NHL.

"I don't care how big or small he is, he can play," Brooks was quoted as saying in Pavelich's second year with the Rangers.

Pavelich scored 99 goals in his first three of five seasons with the team. He played in more than 350 NHL games in a career that spanned seven seasons.

"He was knocked down often," a Star Tribune article said at the time, but "he always got up."

Pavelich played hockey because he loved the game, not because he was seeking glory, friends, family and former teammates said.

He was quiet around strangers but opened up to those close to him. He was generous with his time and the good fortune that hockey and real estate development brought him, sending signed memorabilia to the children of friends and relatives, buying bonds for nieces and nephews, and showing up at friends' fundraisers.

He was playful, too, friends and family said. He and a brother pranked his sisters on one of their frequent trips to the Boundary Waters by rustling in the woods to scare them into thinking there was a bear in camp. Afterward, he cracked up laughing.

"When you got to know him well and he felt that he knew you well … it would be a lot of fun," said John Harrington, a fellow Iron Ranger and college and Olympic teammate.

Though Pavelich was described in media reports as a recluse in his post-hockey life, those close to him say he simply preferred fishing and hunting and spending time outdoors with his dogs.

"He's always shunned the spotlight, and he's had some pretty big spotlights on him. But he's never wanted that," Tomassoni said. "I think a lot of people misconstrued that shyness maybe for arrogance in some ways … he's the furthest thing from arrogant."

Confusion and contradiction

Relatives started noticing changes in Pavelich after his wife — a gifted pianist and painter — died in what was deemed a tragic accident in 2012. Kara Pavelich fell about 15 feet from a small bedroom balcony onto rocks on the couple's property in Lutsen, apparently trying to get cellphone reception while Mark was taking a nap. He told responders that he woke up and found her on the ground.

"They were like peas and carrots," Gevik said. "He was lost."

Pavelich's brother-in-law, Mark DeCenzo, remembers loading some of Kara's paintings into his car to take to Pavelich's mother's house, as he said Pavelich had requested. A few years later, Pavelich questioned him about it, he said.

"He thought I was stealing stuff," DeCenzo said. "That was probably the first time I saw something that made me wonder what was going on. … He lost sight of what transpired."

Gevik remembers being frustrated by her brother's puzzling inconsistencies, too.

Mark had decided to sell one of Kara's paintings that had been hanging in an exhibit, saying he couldn't bear to look at it, Gevik recalled. Thinking he might change his mind, Gevik and her husband planned to buy it so that Mark could have it later, she said.

"Pretty soon it was 'Jean, I didn't want to sell that,' " Gevik recalled.

He had been similarly perplexing when he decided to sell his Olympic gold medal and other memorabilia in 2014, Gevik said. He wanted to pay off the mortgage for his daughter's house, he told the family, but kept changing his mind on how much he wanted, to the point where the auctioneer called Gevik.

"What I saw is a lot of confusion and a lot of contradiction," Gevik said.

A psychology major, Gevik talked with her brother about getting help, she said, but he didn't want to hear it. He grew angry instead. She ended up going to counseling, she said, trying to figure out what to do.

It was her counselor, she said, who first suggested that Mark might have CTE.

Growing concern

The calls came into the sheriff's office sporadically over a few years. Mark Pavelich was acting strangely, and his neighbors and family members who called said they were worried. They wanted law enforcement to be aware of what was happening.

Pavelich had accused a neighbor of dumping sludge into his car fuel tank, one caller said. Another believed Pavelich had taken a sledgehammer to a neighbor's boat.

One relative who telephoned said Pavelich was convinced that cookies from a neighbor were poisonous, and he was keeping them in his freezer as proof.

Then, last summer, a Lutsen resident called to report that he had been attacked with a metal pole and identified Pavelich as the aggressor.

Pavelich was booked into the Cook County jail on assault and weapons charges. A criminal complaint described Pavelich as accusing the neighbor of spiking his beer. The victim suffered two cracked ribs, a bruised kidney and a fractured vertebra, the complaint said.

In October, Pavelich was found incompetent to stand trial on the charges. Later, a psychologist who examined him for civil commitment proceedings determined that he suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder as well as mild neurocognitive disorder due to traumatic brain injury, saying his condition is "likely related" to the head injuries sustained over his lifetime.

DeCenzo and other family members can't help but wonder whether the trauma of losing his wife so suddenly — and grieving and living alone after that — made his underlying illness unmanageable.

"My guess is … he was probably fighting it and she was probably the stabilizer," DeCenzo said. "Somebody at home to keep you grounded."

Diagnosis tricky

That is a possible scenario, said Dr. Bennet Omalu, a pathologist who has done research on CTE but was not familiar with the details of the Pavelich case.

"With all types of diseases, when you have social support, your disease is better managed," Omalu said, adding that social stressors "are more likely to aggravate your underlying brain disease."

While CTE can be confirmed only in an autopsy, scientists are working on a test to detect proteins associated with the disease in living people.

But doctors in some cases are now making a presumptive diagnosis of CTE, as they do in other types of dementia, Omalu said, relying on the standard of a "reasonable degree of certainty — meaning more likely than not."

CTE is not the only type of brain damage an athlete can suffer, Omalu said. And if someone's family has a history of mental illness, high-impact sports can increase the likelihood of manifesting mental illness, he said.

"Maybe with treatment … medication, his symptoms can subside," Omalu said.

Pavelich's family is hoping he will be released from the state facility where he has been housed since a judge found him "mentally ill and dangerous" in December.

A hearing to make a final determination on whether he should remain civilly committed indefinitely is expected to be held this spring.

In the meantime, some former NHL players are working with Pavelich to establish a therapeutic retreat ranch where players, their families and others struggling with mental illness and brain disease can go for counseling, animal therapy and other programs, as well as supporting research on CTE. They have started a fundraising campaign on GoFundMe.

"You're a good person your whole life …" Gevik said, her voice trailing off as she teared up thinking about what's happened to her brother.

Now, she said, she just hopes something good can come from it.

"I told him, 'We can help a lot of people this way.' "

Staff researcher John Wareham contributed to this report. Pam Louwagie • 612-673-7102

Want to share info with the Star Tribune? How to do it securely

'Safe recovery sites' would offer syringes, naloxone and more to people using drugs. The plan could be in peril.

New Minnesota GOP leaders seek peace with party's anti-establishment wing

Who is Republican Lisa Demuth, Minnesota's first House speaker of color?