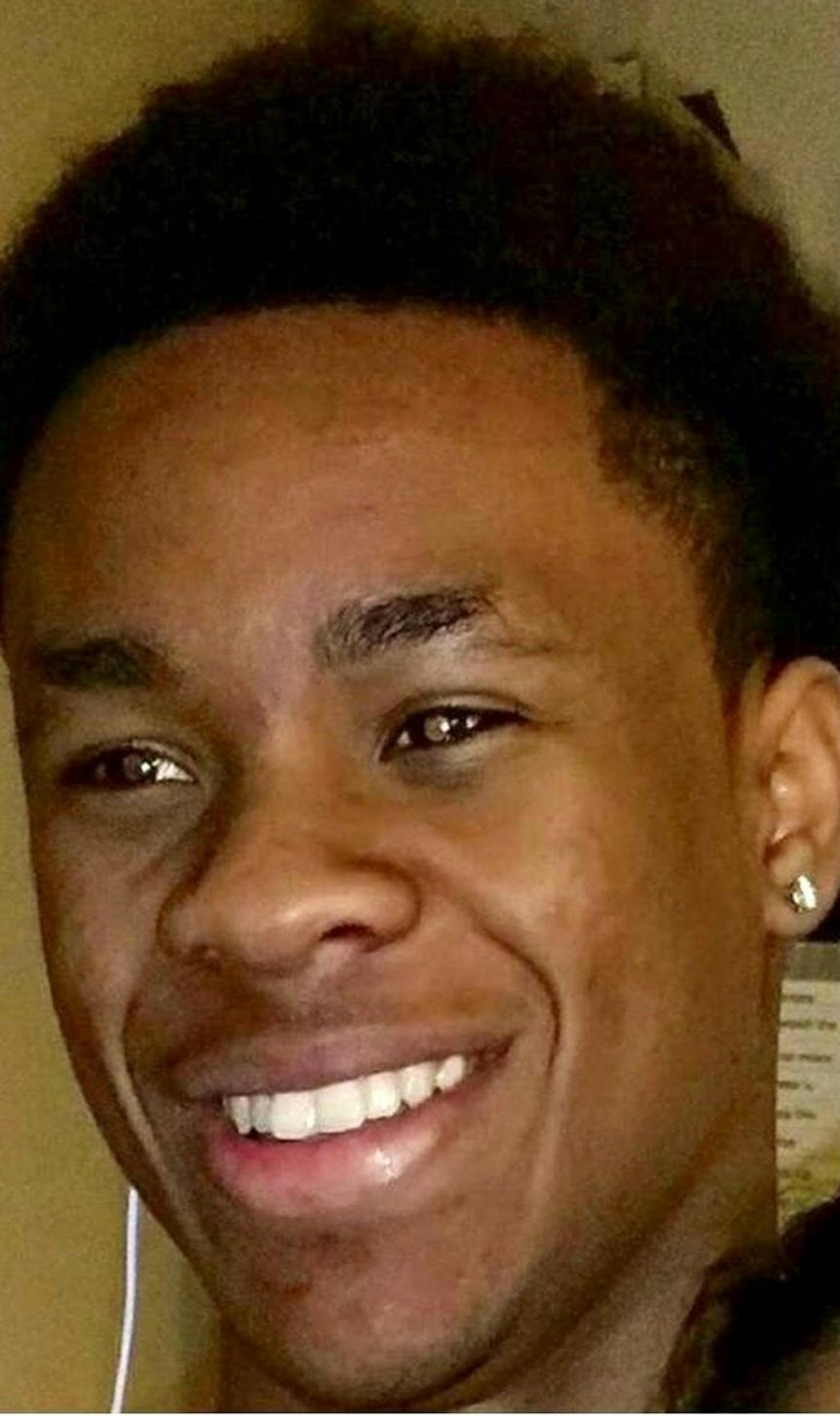

The family of Amir Locke, the 22-year-old Black man shot and killed by Minneapolis police during a predawn raid last February, is suing the city and the SWAT officer who pulled the trigger, alleging that the no-knock warrant that resulted in his death is consistent with the city's "custom, pattern and practice of racial discrimination in policing."

The 35-page federal lawsuit filed on behalf of his parents, Karen Wells and Andre Locke, contends that officers violated Locke's constitutional rights when they burst through the apartment door without properly announcing themselves, willfully ignoring the danger posed to any innocent civilians inside.

"Amir Locke didn't even have a chance," civil rights attorney Ben Crump said at a Friday morning news conference. "He was practically in slumber when the police did what they do so often with Black people: They shoot first and ask questions later."

The lawsuit demands accountability amid renewed public outrage over police killings nationwide, including the fatal beating of 29-year-old Tyre Nichols last month in Memphis. It was filed on the one year-anniversary of Locke's death, observed Thursday with a gathering at the Minnesota State Capitol where Locke's relatives called on the attorney general to reopen the criminal investigation into the officers involved.

City officials declined to comment on the pending litigation beyond a short statement, saying they "will review the complaint when they receive it." The Police Officers Federation of Minneapolis could not be reached for comment.

In an emotional statement to the media, Andre Locke vowed to keep fighting so that his son's death "will not be swept under the rug" and to help eliminate no-knock warrants across the country.

"You will be the face of justice for many and you will save lives," he said of Amir, wiping away tears. "This is not in vain. You stood for something in America. Your legacy will remain for each of us."

Attorneys did not specify how much the family will seek in compensation.

On the morning of Feb. 2, 2022, a Minneapolis SWAT team stormed into the Bolero Flats apartment building downtown in search of evidence related to a St. Paul homicide investigation.

An officer's body-camera recording showed police quietly unlocking the apartment door with a key before barging inside and yelling, "Search warrant!" as Locke lay under a blanket on the couch. When an officer kicked the couch, Locke stirred and emerged holding a pistol in his right hand.

Officer Mark Hanneman fired three times, striking Locke in the face, chest and arm.

Locke, a DoorDash delivery driver and aspiring rapper who legally possessed the gun, was not the subject of the search warrant and had no criminal record.

"Any reasonable officer would have understood that Amir needed an opportunity to realize who and what was surrounding him, and then provide Amir with an opportunity to disarm himself," the suit reads. "Hanneman failed to give Amir any such opportunity. ... Instead, Hanneman fired three shots while Amir was still covered in a blanket on a couch where Amir had been resting peacefully only 10 seconds before the SWAT entry."

Hanneman told investigators that, in that moment, he feared for his life and needed to use deadly force. Two months later, then-Hennepin County Attorney Mike Freeman and Attorney General Keith Ellison declined to file charges against Hanneman, because they didn't think they could get a conviction under state law.

The family's lawsuit alleges that Locke was killed during the execution of the no-knock warrant, despite the fact that he never raised the weapon in the direction of any officer or placed his finger on the trigger.

Locke's killing led to a moratorium on the controversial practice. St. Paul police initially applied for a standard search warrant in connection with the homicide investigation, but had to resubmit the request after Minneapolis police insisted on a no-knock operation.

Officers were sent to the building looking for Locke's cousin, Mekhi Speed. The 17-year-old was a suspect in the St. Paul homicide but who lived in a different unit with his mother. Locke was staying with Mekhi's older brother, Marlon, and Marlon's girlfriend at the time police raided both apartments.

None of the three occupants was named on the warrant, and police never offered evidence that suggested any were connected to the case.

Locke's grieving relatives consider that sloppy investigative work.

"If you boot up or suit up a SWAT [team], you're supposed to know who is on the other side of that door when you're going up in there," said Wells, Locke's mother."

No-knock warrants, which allow police to enter a property without announcing their presence beforehand, have been banned in cities across the country after they resulted in the deaths of innocent civilians. Minneapolis restricted the use of the unannounced raids in 2020, as part of a series of reforms made in the wake of George Floyd's death. At the time, Mayor Jacob Frey claimed he banned no-knock warrants for "all but exigent circumstances".

But court and email records suggest the practice not only continued until Locke's death but persisted at a pace that far surpassed that of standard knock-and-announce entries. A Minneapolis Police Department spokesman informed the mayor's office that the department conducted 87 no-knock warrants in the year after his original policy change, according to the lawsuit.

"We should have learned from Breonna Taylor," attorney Jeff Storms said, referencing the Louisville, Ky., woman who was killed by police in a similar no-knock raid more than a year before Locke.

"And instead of acting on that foreseeable risk of harm, they engaged in a level of political placating of everybody locally, and told us that there was a ban when there wasn't."

In the four months before Locke's killing, the suit says, "Minneapolis executed no-knock warrants only in homes of color, predominantly in Black homes, and not once in the homes of non-Hispanic Whites. The application for and the execution of the no-knock warrant that resulted in Amir's death is consistent with Minneapolis' custom, pattern and practice of racial discrimination in policing."

Storms, who also serves on the Locke family legal team, accused the city of ignoring the enormous risks involved in serving no-knock warrants — even after a series of botched raids by Minneapolis police officers that stretch back decades.

The lawsuit recounts four such instances, including a 2007 case in which police targeting the wrong home exchanged gunfire with Vang Khang, who assumed the officers were burglars. His wife and six children, ages 3 to 15, were in the house.

Police blamed the mix-up on an informant's faulty intelligence.

With full control of the state government, DFL lawmakers have vowed to rekindle police reform discussions during the current legislative session and may reconsider banning no-knock search warrants.

,

At least three Democrats have agreed to take up the issue and pursue a bill in Locke's name, his father said. In the meantime, attorneys plan to aggressively seek a form of injunctive relief that makes it financially prohibitive for police to continue operating in that manner.

"How many times do we have to say, 'Never again'? I'm so tired of saying 'never again' because it keeps happening," said attorney Antonio Romanucci.

Wrongful death lawsuits filed against police officers rarely go to trial in Minnesota because city officials fear that juries may award even more money in damages than a settlement. Payouts for fatal police encounters vary widely by jurisdiction, but high-profile cases that garnered national media attention in recent years have resulted in massive sums.

Minneapolis paid a record $27 million to settle a lawsuit brought by Floyd's family, a figure hailed by their legal team as the largest pretrial settlement of its kind in U.S. history.

That total surpassed the previous $20 million record for the city, awarded in 2019 to the family of Justine Ruszczyk Damond, a white woman killed by a Black officer after she reported a possible assault in a nearby alley.

Those payouts dwarfed compensation for all previous police-related settlements in the region, including those in the cases of Philando Castile, David Smith and Jamar Clark.

Since 2006, Minneapolis has paid at least $75 million to settle officer misconduct claims or lawsuits.

Star Tribune staff writers Abby Simons and Jeff Hargarten contributed to this report.

Want to share info with the Star Tribune? How to do it securely

'Safe recovery sites' would offer syringes, naloxone and more to people using drugs. The plan could be in peril.

New Minnesota GOP leaders seek peace with party's anti-establishment wing

Who is Republican Lisa Demuth, Minnesota's first House speaker of color?