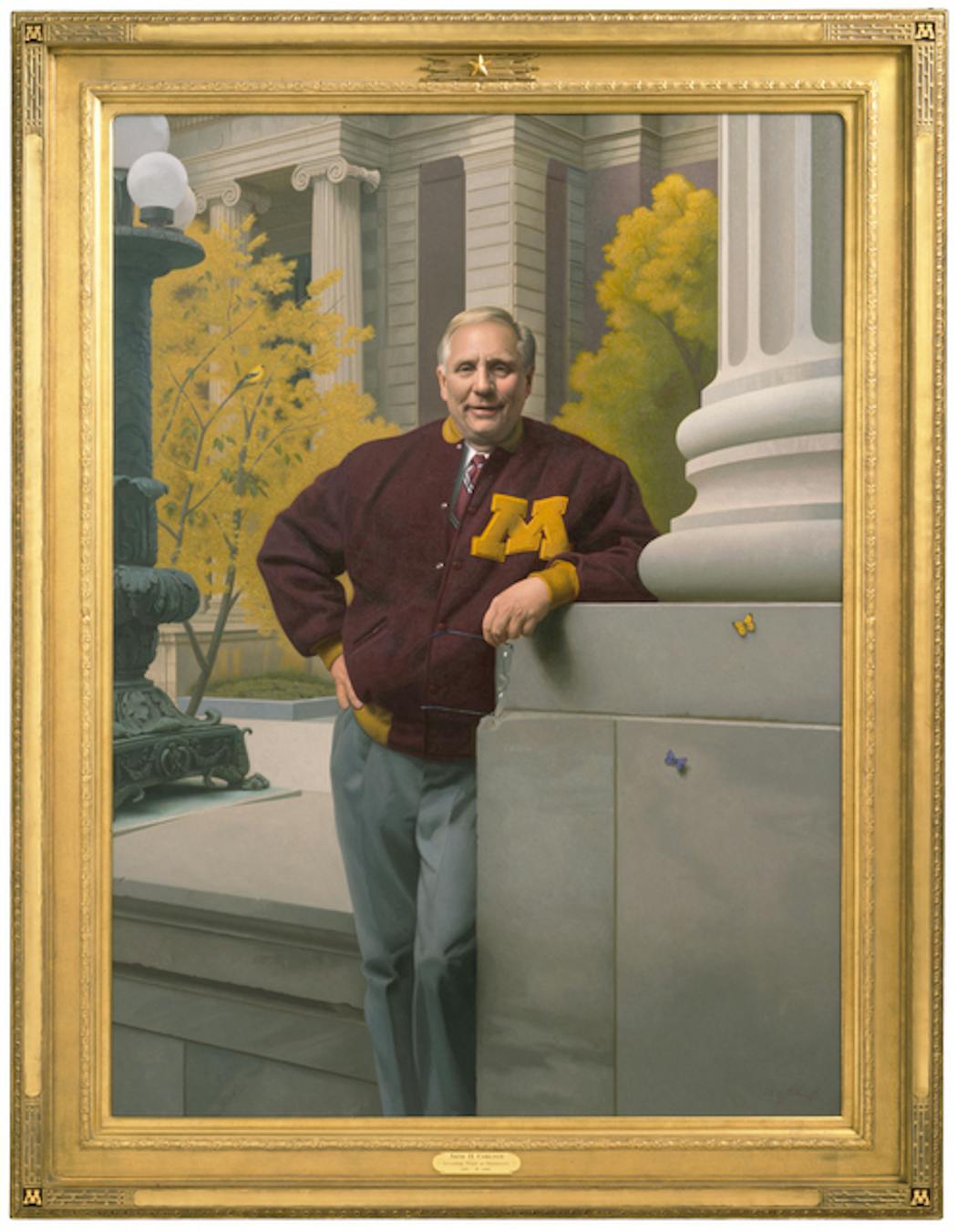

Arne Carlson was Minnesota governor from 1991 to 1999. Previously, he served on the Minneapolis City Council, was a member of the Minnesota House and was state auditor. Considered a moderate Republican, Carlson's hallmark conservation initiative while governor attempted to clean up the Minnesota River.

In the interview below, Carlson, 88, details his efforts to protect Minnesota's surface and subsurface waters, including Lake Superior and those in the Mississippi River watershed, which he believes are particularly threatened by northern Minnesota mining proposals. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q As governor you emphasized resource conservation. But you're from the Bronx, in New York City. How did the outdoors become important to you?

A When I was about 9, my father bought an encyclopedia. Reading it opened a different world to me with animals, vast forests and the incredible variety of life in oceans. I particularly liked maps showing states colored green, indicating open spaces. Michigan, Wisconsin and Minnesota all had lakes and woods and streams.

Q How did you end up in Minnesota?

A I applied to graduate school in each of the three "green'' states, and Minnesota was first to accept me. I wanted to take a train into Minnesota so I could see more of it, and it was a delight.

Q You've said Minnesota faces a water crisis exacerbated by mining proposals in northeast Minnesota. Explain.

A Globally, water demand is exceeding supplies, and the same is true in Minnesota. Unfortunately, we have ignored every warning. The state has nearly 3,000 waters impaired by pollution, with hundreds more added each year. The proposed mines could add to that dramatically.

Q How did you become aware of the mines' possible effects on water?

A I've been studying it for five years. I've always felt if a choice must be made between commerce and the environment, the environment should win. These mining proposals would risk not only the BWCA but Lake Superior and the Mississippi River watershed. Their impairment would doom Minnesota, and it's not worth the risk.

Q Some minerals mined under the proposals are needed to transition to a greener society, including increased use of electric vehicles.

A True. We're in conflict in Minnesota and globally between the need for precious metals and the need to protect our resources, water especially. For the time being, the Biden administration has halted the Twin Metals project adjacent to the BWCA, which is good. Equally threatening, however, is the PolyMet proposal and the proposed Tamarack mine.

Q Proponents of the PolyMet mine, which is in litigation, say the mine can be operated safely. Why shouldn't Minnesota believe them?

A Among many reasons is that a majority of PolyMet is owned by Glencore, a Swiss multinational company that last year pleaded guilty and paid more than $1.1 billion in fines to resolve violations of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act and commodity price manipulation. Glencore also has been cited among mining companies as among the worst human rights violators. Minnesotans should ask: "Why would we do business with a company like this?"

Q You've posed that question to Gov. Tim Walz in op-eds as well as in letters to the governor.

A I've received no response from Gov. Walz. We had a phone call set up, but he canceled. I campaigned for the governor, which is unusual for a Republican. He's said his administration would be transparent. It's not true.

Q But on Feb. 24, Department of Natural Resources Commissioner Sarah Strommen replied to you on behalf of the governor, saying "state law does not authorize … the Governor to dictate which companies own, invest in, or propose a mining project." Strommen also said, "The permit to mine previously issued for PolyMet is not currently in effect due to ongoing legal proceedings. Following the conclusion of the contested case hearing process currently underway, the DNR will address any recommendations from the administrative law judge and other aspects of the earlier Supreme Court decision prior to making a final decision on the permit."

A It's simply not true that the governor doesn't have the power to initiate laws, to initiate hearings and to go to the people to explain and discuss the scope of the tradeoffs being considered with mining. The governor has had four years and he hasn't done anything. As for Commissioner Strommen, she's making my broader point about mining in Minnesota, namely that our laws governing it are outdated. Former DNR Commissioner Tom Landwehr was correct when he said, "[The mining permitting process] is a very narrow prescriptive. It doesn't look at economic, it doesn't look at cultural, it doesn't look at quality of life. It's a very narrow prescriptive. It doesn't look at health."

Q Aren't the state's mining laws the Legislature's responsibility?

A Absolutely, but the Legislature doesn't act, in part because not enough Minnesotans know about the problem, and among those who do, too few are active politically. This disconnect between citizens and lawmakers is part of a much larger problem stemming from the 2010 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Citizens United, the effect of which is that officeholders now spend their time courting big donors, while the interests of regular people are too often ignored.

Q Even so, you've garnered quite a following through your frequent writings and letters circulated among supporters.

A Still more people need to be involved. It's our survival we're talking about. Hunters and anglers will be among the most affected if we don't change direction. We need their support.

Q But we, all of us, also need the minerals that mining produces …

A Agreed, and at least three guidelines should govern mining in Minnesota:

One: No tradeoffs between water protection and minerals. Water always comes first.

Two: Mining should be done in dry environments.

And three: If mining must occur in wet environments, make sure it's done with more stringent protections than we currently have, and, most importantly, make sure it's done with the right people.

Anderson: Canoeist found dead in BWCAW was experienced

Anderson: In early June, Minnesota fish are begging to be caught. Won't you help?