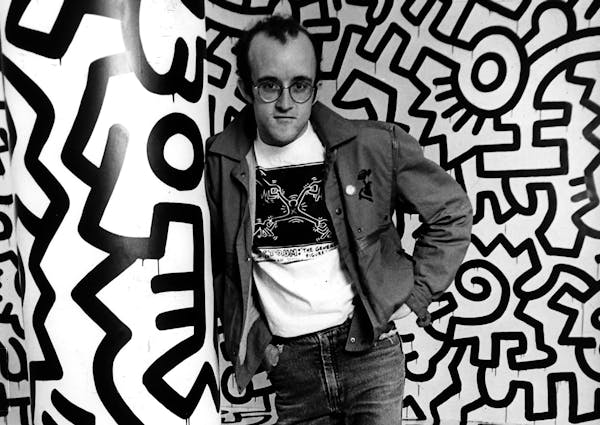

Tucked away within the sprawling Keith Haring exhibition at the Walker Art Center is a section outlining his time as an artist-in-residence at the museum in 1984. As part of that program, he painted a large mural: a figure with a dog-human body and computer head. Now, in the Cardamom restaurant off the Walker's main entrance, there's a replica of that same mural.

So what happened to the original mural, which Haring painted in the hallway between the museum and the old Guthrie Theater on March 15, 1984?

"The mural was painted over," according to then-Walker curator Adam Weinberg, who would go on to become director of the Whitney Museum of American Art. No one objected to it being temporary, Weinberg said. "It was always expected to be — as was true with most of his projects at that time."

A contract provided by the Walker states that Haring agreed to make a mural that would be subject to removal by Sept. 15, 1984, at the sole discretion and expense of the Walker.

Haring painted the mural quickly, in a single day, as was his style, according to a 2012 article on the Walker's website. What started as a blank wall became a figure with a computer head, a brain on its screen. A glowing money symbol popped up too, common for Haring's critiques of capitalism. The bright orange background makes the green-outlined figure feel like it will leap off the wall and into the corridor.

During his residency, Haring collaborated with ballet dancer Jacques d'Amboise, working with elementary school students to produce sets and costumes for a new production presented as part of the Walker's ArtFest celebration.

This happened nearly more than 40 years ago, and according to public art historian Michele Bogart, a professor emeritus at SUNY Stony Brook, this practice of a temporary mural wasn't uncommon.

Haring's "whole output at the very outset was this very ephemeral kind of stuff, some of it almost being subway vandalism, and then it got validated," Bogart said. "Part of his significance always lay in that kind of intersection between these ephemeral, populist kinds of interventions and then the subsequent popularity of them and marketability of them."

Longtime Minneapolis gallerist and art dealer Doug Flanders wondered about the decision to not make Haring's mural a permanent fixture.

"I always thought that they should have the artists making temporary murals paint on gigantic canvases that could be taken down and rolled up for posterity," Flanders said. "The Haring is one example."

Weinberg brought Haring in just two years after his breakout 1982 exhibition at Tony Shafrazi Gallery in New York City. By 1984, people knew of Haring's work, from his chalk drawings that he did in empty ad spaces on subway platforms to his larger-than-life murals in New York. Many of the latter still exist today.

"I don't criticize institutions that make these arrangements in the past and then don't live up to what people would have liked to have seen now. It is not unique," Bogart said. These days, "the museum mural phenomenon is less prevalent. In the late '60s and '70s and on into the '80s, there were tons of these things being done as community art."

Haring's exhibition at the Walker, "Keith Haring: Art Is for Everybody," continues through Sept. 9.

The 5 best things our food writers ate this week

A Minnesota field guide to snow shovels: Which one's best?

Summer Camp Guide: Find your best ones here

Lowertown St. Paul losing another restaurant as Dark Horse announces closing