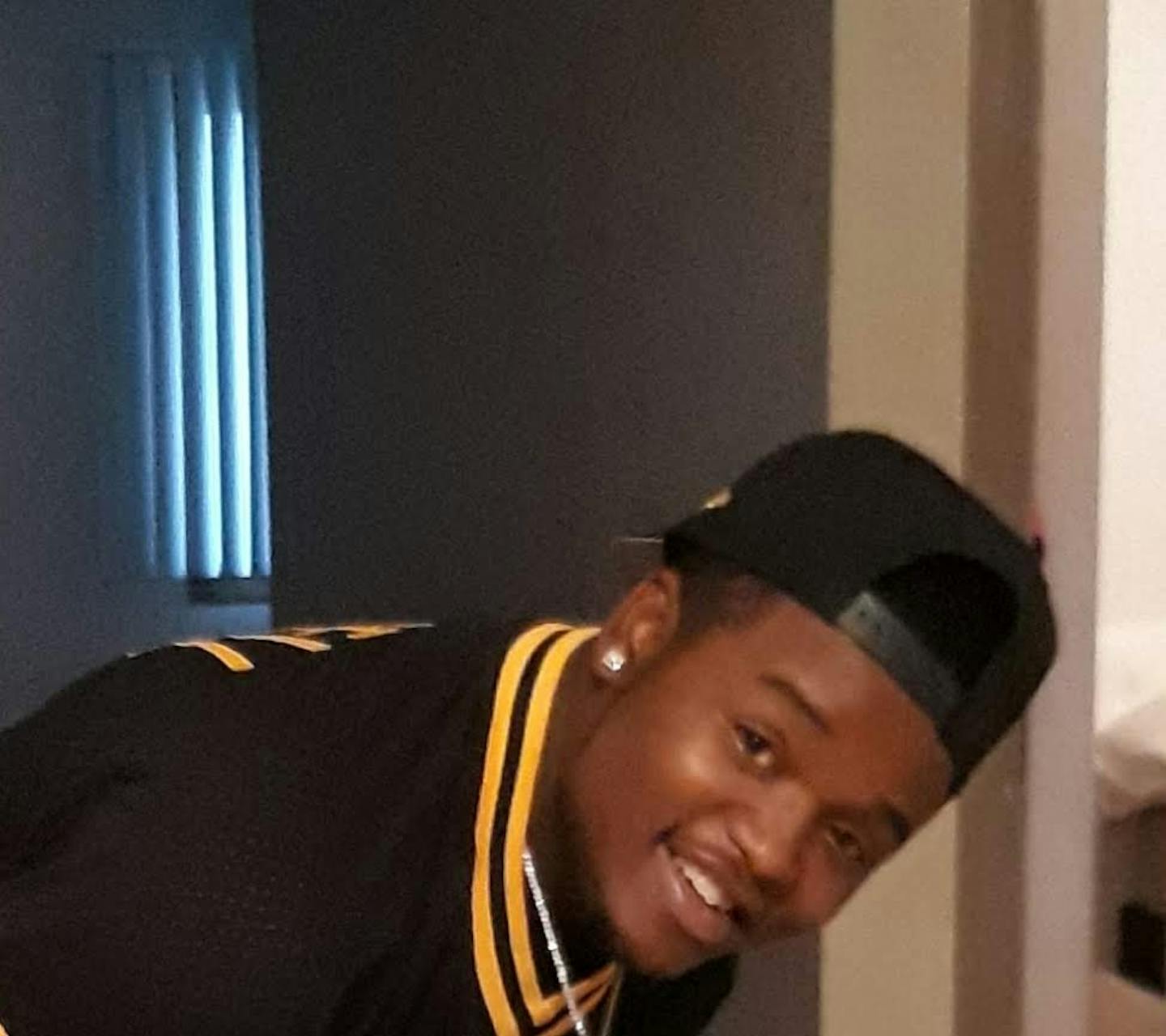

Latisha Fairley studied the footage showing two figures approaching her son's car, and she wondered if Keithshon had known them. The men wore surgical masks, so Fairley couldn't make out their faces. But she knew how this video ended. And if it was just a botched robbery, she wondered, then why did they need to shoot him six times?

More than three years after a Minneapolis police investigator first showed her the security footage, Fairley is still replaying the video in her head, still asking the same question of those two mystery men: Why did you kill my son?

"He wasn't robbed," Fairley said. "He was just killed. Why? It's hard not having closure, not knowing."

She is not alone in her long wait for answers. Keithshon Fairley's murder, outside a south Minneapolis bar on Dec. 23, 2020, is one among 77 open homicide cases left over from 2020 to 2022 — a period at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic when a violent crime wave peaked — according to police records analyzed by the Star Tribune. Of those, 35 occurred in 2020, most during the chaotic months after George Floyd's murder.

Even as violent crime and homicide rates have dropped in the past two years — and Minneapolis police are solving more murders than in previous years — the number of open cases for this period remains higher than any in at least three decades.

Stuck in the wake of the unsolved murders are families like Fairley's, left broken and forced to move on without accountability for those responsible. Some say they've given up hope that they will ever see their loved ones' killers brought to justice.

"I don't believe it's ever going to get solved," said Fairley, of 23-year-old Keithshon's case. "I don't believe they're investigating it anymore. I haven't heard anything in over a year. And it kills me."

The Star Tribune reached out to dozens of people whose relatives appear in the unsolved murder backlog from this three-year period. Of those who responded, some said they are still waiting to retrieve their loved one's personal belongings collected by law enforcement after the crime. Many had not heard an update for years, and expressed confusion, anger or defeat over why they couldn't get messages returned from investigators.

"When I was grieving, I called every single day," said one mother, who declined to be publicly identified, fearing it may hinder the investigation. "The information we've received is slim to none."

Ronald Fleming, a custodian at North High School, said police have never contacted him since the September 2020 murder of his 26-year-old son, Eugene, even to inform him that it happened. What he does know about Eugene's shooting has come from word of mouth around his neighborhood.

"I'm trying to still figure out why and how and when," he said. "I don't know what to do. I just know I'm still in pain."

Minneapolis police leaders agreed the unsolved case backlog is a problem. They say a higher rate of unsolved cases harms community trust and may breed more violence. But police officials said it's a result of a nagging staffing shortage that has fundamentally changed the way the department investigates murders over the past four years: At the same time that homicides and other metrics of violent crime surged to the highest rates since the 1990s, an unprecedented wave of retirements and resignations has left the Minneapolis Police Department ranks 40% below pre-2020 staffing levels — stretching far fewer investigators over a ballooning caseload.

Last fall, Chief Brian O'Hara combined the homicide unit and shooting response team — a stand-alone outfit dedicated to investigating nonfatal gun violence — to pool resources. But when each day is about triaging 911 calls, O'Hara has said, police officers can't spend as much time processing crime scenes or responding to victims' families.

"We're not using staffing as an excuse," O'Hara told the Star Tribune in a recent interview. "We are going to get through this, and we are going to do a better job, even if we have fewer people next year. But this is a real issue and we are well aware of it. And we're 100 percent in agreement that we need to find whatever ways there are to try and be better with this."

A nationwide problem

Minneapolis is not the only major U.S. city struggling to clear a runaway murder backlog.

In 2020, as homicides surged across the country, the rate of cases solved by law enforcement plummeted. By the end of 2020, only one in every two cases was being closed nationally, according to FBI data.

"This should be a golden age for homicide clearance," said Thomas Hargrove, founder and chairman of the nonprofit Murder Accountability Project, which tracks unsolved cases. "But we're at an all-time low."

Hargrove pointed to several factors limiting law enforcement's investigative capacity: strained city and police budgets, a shortage of detectives and forensic specialists to canvas neighborhoods after crimes, lengthy delays at state testing labs and higher evidence standards for prosecutors compared to 50 years ago.

Before 2020, the Minneapolis homicide unit consisted of 12 to 14 investigators in charge of solving 32 to 50 murders a year, based on a decade of year-end data. In 2021, Minneapolis police counted 91 murder cases, some involving multiple victims. After merging the homicide and violent crime units, 14 sworn officers are now tasked with solving all shootings, fatal or not.

"We're doing what we can with what we have," said Cmdr. Emily Olson, a former homicide detective who oversees the new division.

Olson wouldn't venture to guess the average caseload for her team, which she said changes based on the investigator's background and experience. But Olson and O'Hara acknowledged the number is well above the U.S. Department of Justice standard of roughly five homicides per investigator.

Still, in 2021, Minneapolis investigators solved 55 homicides — more than the 40 total murder cases the department recorded on average in pre-pandemic years.

"That's amazing work," Olson told the Star Tribune. "They want to give these families a sense of peace and some kind of closure."

They are still investigating unsolved murders dating back to 2019, she said. But after five years without progress, they will reclassify them as cold cases.

Stolen time

Charlie Jones-Burge always knew her son might die young.

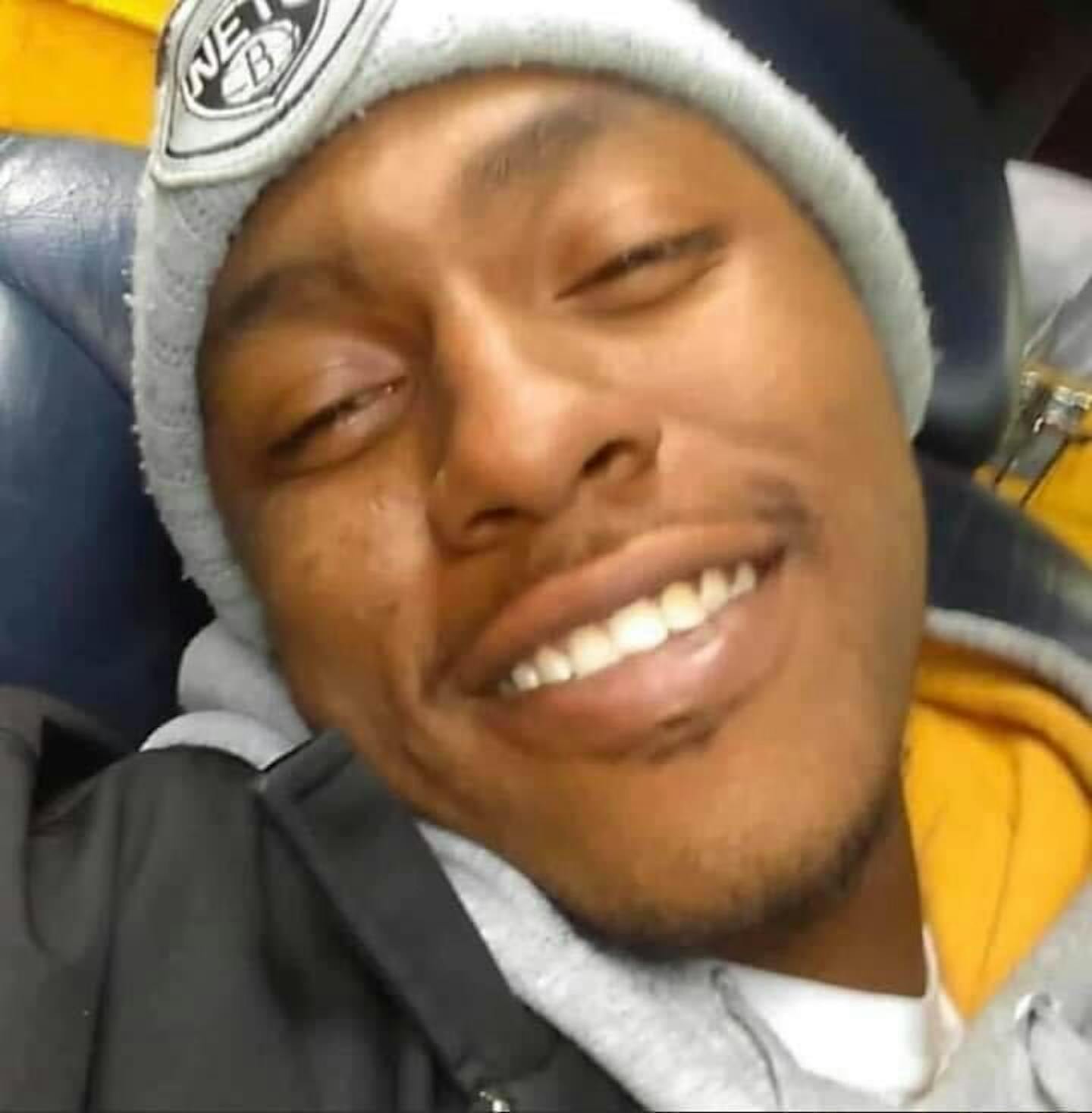

Oliver Perkins III was born with sickle cell disease, a genetic blood disorder. When the pandemic hit, Oliver was 18 years old and living alone, and she worried his condition made him vulnerable.

But in all her imagining, Jones-Burge said it never crossed her mind that Oliver would be gunned down at a convenience store, apparently for being in the wrong place at the wrong time.

"I didn't think it would be like that," she said, wiping a tear from her cheek, in an interview at the Get Ready Rooms, a salon she owns on Minneapolis' North Side. "If I was going to lose him to his sickle cell, I would have time to be with him in the hospital. We would have time to, like, figure it out."

The shooting happened on Oct. 8, 2020 — her birthday. Jones-Burge was talking to Oliver on the phone while he ran an errand on Nicollet Avenue near E. 18th Street. She said she heard a series of popping noises through the receiver.

"I'm like, 'Oliver? Oliver?' And he didn't respond to me."

Jones-Burge went to the shop where it happened the next day, after Oliver died in the hospital, and the clerks let her watch the security footage. She said it showed Oliver on the phone, smiling, as a hooded figure burst in, shooting. The other people in the shop ran. Oliver tried to run too, not realizing he'd been hit, and then he collapsed.

After seeing the video, Jones-Burge went up to his apartment. The TV was still on, a pot of chili congealing on the stove.

Oliver had known his killer. Police said Oliver told them before he died that he'd seen him around the neighborhood, but he didn't know his name. The next year, the investigators stopped calling, leaving her to wonder if they also stopped looking.

"Some get solved, some don't," she said. "But communication shouldn't be this hard."

She saw one of the officers again in May 2021, at the scene of another killing: the father of her grandchild she's helping to raise, 23-year-old Quentheus Watkins (another case that remains unsolved). She pressed the officer about Oliver, she recalled, and he said it may have been a case of mistaken identity.

"I'm part of this club that I don't wanna be a part of. Because nobody else understands what it's like to lose a child."

Distrust grows

Lt. Richard Zimmerman hadn't been sleeping much. His phone rang every few hours.

On May 27, 2020 — two days after Floyd's death under the knee of his colleague — the veteran head of Minneapolis' homicide unit was called to a local pawnshop where the owner had reportedly shot and killed a suspected looter.

A hostile crowd assaulted officers attempting to revive the 43-year-old victim, as fires smoldered nearby on Lake Street. The ambulance couldn't get through and forensic analysts were unable to process the scene until the next day. By then, any surveillance footage that may have captured the fatal shooting was long gone, along with everything else in the ransacked store.

Starting that tumultuous week, as distrust in law enforcement spread in protests and riots across the country, Zimmerman found fewer witnesses willing to talk. He tried to reason with them: "If you're not going to cooperate, and no one else is going to cooperate, we're not going to get justice for this guy."

Zimmerman's team responded to about 70 more homicide scenes in the second half of 2020.

"After George Floyd," he said, "the dam burst."

Zimmerman, who signed an open letter condemning Derek Chauvin after Floyd's murder, developed a refrain when speaking to witnesses who were suspicious of police at this time, he said: We are not the officers involved in Floyd's death. What happened was wrong. We're working around the clock to solve this case. And we need your help.

Staffing within the homicide unit dipped to an all-time low of 10 investigators in 2021, as elected officials hotly debated whether to dismantle the police department.

"I asked for more bodies constantly," said Zimmerman. "It was kinda beg and borrow."

When three young children were struck by stray bullets in separate North Side shootings over a two-week period in May 2021, it jolted the conscience of a city already on edge. Only one, Ladavionne Garrett Jr., survived, although he was left permanently disabled. His case was never solved, nor was that of 6-year-old Aniya Allen.

Zimmerman said investigators still cling to hope that one day they will find the killers. In rare moments of downtime, they take the files off the shelves and review them again. Zimmerman attends Allen's memorial at 36th and Penn avenues N. each year, pleading with the public to come forward with information.

"We need to keep those cases in the forefront of people's minds," said Zimmerman, now commander of the Major Crimes unit who serves as a community liaison. He acknowledged that overworked detectives don't always return phone calls to victims' families as promptly as they should, especially when they've hit a roadblock in the case.

"Keep calling up," he urged the families of the victims. "Eventually, you'll get a call back."

Most victims Black men

In the United States, most of the murder cases that go unsolved involve Black victims, according to the Murder Accountability Project.

That holds true in Minneapolis: about 80% in those 77 cases from 2020-2022 were Black, mostly men, who were killed in the city's most diverse and working-class neighborhoods, such as Hawthorne and Jordan on the North Side and the Phillips communities on the South Side. Victims ranged in age from children to nearly 60, but most were in their 20s and 30s.

Most of the other victims were also people of color: about five were Native American, three were Hispanic. Four were white.

Ronald Fleming, a longtime north Minneapolis resident, said he heard about his son Eugene's killing from his sister. He doesn't know how she'd found out. He remembered frantically pacing around the house on that dark day in August 2020, trying to figure out if it was true. Fleming called HCMC, and a hospital employee confirmed that Eugene had been shot.

"That's how I found out," he said.

At the time of his murder, Eugene was living with his girlfriend and their three sons. Fleming said he doesn't understand why the police never came to his home afterward. "That's what I see on TV," he said. "Why didn't y'all do it in real life?"

Around the time of his son's killing, Fleming said, his mother passed away. His roommate died, and then so did Eugene's mother.

"I'm surprised I'm holding up," Fleming said "It's like, if I can get some closure on one thing, I'll probably be OK with the rest of it. Because the other people who passed away died of natural causes — but they killed my son."

DOJ resources coming

To help clear the backlog, the department has leaned on outside help, like the Bureau of Criminal Apprehension and Hennepin County Sheriff's Office.

This summer, the department will team up with the Justice Department, which will provide intensive training, technical assistance and a comprehensive shooting assessment through its National Public Safety Partnership. Minneapolis will receive an injection of federal resources over the next three years, as well as recommendations on how to manage caseloads and raise clearance rates.

As police ranks continue to shrink, the city is investing more in recruitment efforts aimed at rebranding the badge — and attracting a new generation of reform-minded officers. That campaign could put more cops on the streets, but it won't immediately translate to more senior positions like homicide investigators.

The department has also turned to civilian analysts, who mine hundreds of hours of video evidence and assist with clerical work on pending criminal investigations.

In the meantime, as new murders continue to stack up, at least 77 cases are getting colder by the day.