Gordon Kirk wanted to parachute into World War II battlefields. But because he was Black, and the U.S. Army was segregated, he wound up driving a troop truck instead — delivering soldiers and armor to the Battle of the Bulge at the end of 1944.

As Adolf Hitler's German army staged a last counteroffensive, sleep required that Kirk take cover under his truck near Bastogne in southern Belgium.

"The snow was deep on the hillside and we had our Army-issued coats, boots and sleeping bags that were so thin you could read a newspaper through them," said Kirk, now 100, while gazing out the window of his longtime home on Fuller Avenue in St. Paul's old Rondo neighborhood.

Kirk asked me to feel his chilled hands. He still suffers from lingering numbness, for which the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) agreed to compensate him years later.

Grasping Kirk's hands, as I did, made history tangible. Those hands steered vehicles and transported body bags at Omaha Beach six days after D-Day. They held a handkerchief over his nose as he joined Allied forces liberating the Nazi concentration camp in Dachau.

"I drove in the second day and the stench was so tough," he recalled. "The Jewish people we found were just skin and bones."

In the weeks that followed, Kirk's hands held DDT sprayers used to kill the lice that was clinging to enslaved Czech and Polish laborers who had built Hitler's highways and war machines.

After the war ended, Kirk's hands served diners on Northern Pacific trains before they piloted St. Paul streetcars through the 1950s. He remembers navigating the tricky incline in the tunnel where Selby Avenue met the Cathedral of St. Paul.

"I had all the routes — Grand Avenue, University, Randolph — until the buses came in and replaced the streetcars," he said. "I didn't want to drive buses."

He then spent 33 years as a skycap, hauling luggage at the airport from 1958 into the 1990s for Braniff and Northwest airlines. He turned down a management offer to stay in the skycaps union, enduring a few strikes while enjoying free flight perks.

Kirk was born in Helena, Mont., on March 23, 1923. He was 10 when his father's work with the Northern Pacific railroad took the family to St. Paul during the Great Depression, and he graduated from St. Paul's Marshall High School in 1942.

The family lived for a while in Rondo before the neighborhood was gutted to make way for Interstate 94 in the late 1950s. "They shook it up, tore it down and displaced the grocery stores, tamale stands and barber shops," he said.

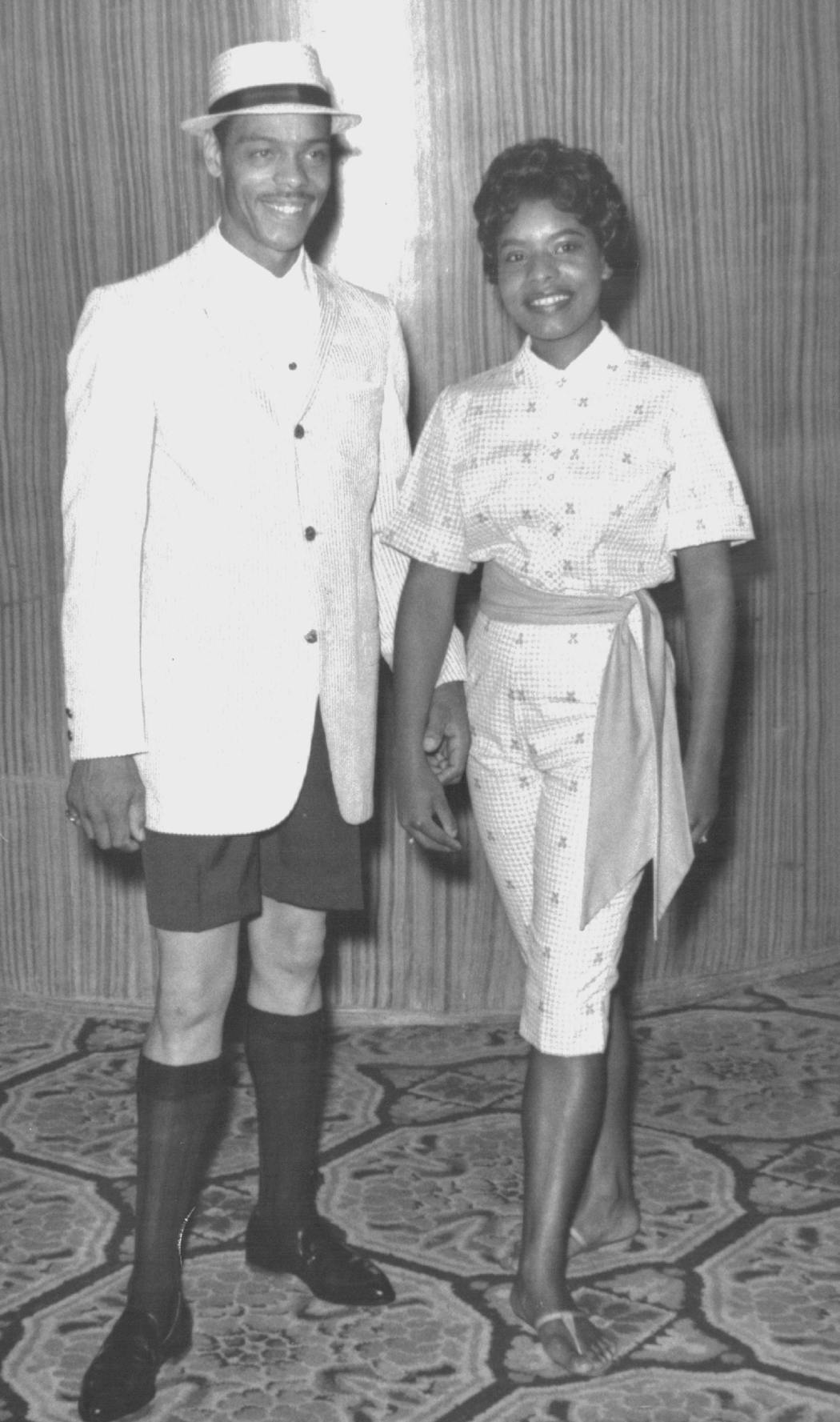

Kirk married Gwen Ray in 1958 and purchased the house on Fuller Avenue in 1960 for $15,500. The couple raised three children and started an organization to raise money for neighborhood playgrounds.

Kirk became the first Black commander of the Minnesota chapter of the Veterans of Foreign Wars in 1995 and went to work for the VA in 1997, helping countless vets navigate pension and health care benefits. Gwen died in 2005.

Gov. Tim Walz and St. Paul Mayor Melvin Carter were among those marking Kirk's 100th birthday last month.

"He's a product of Rondo who never left our community,'" said Nathaniel Khaliq, president emeritus of the NAACP's St. Paul branch, who has known Kirk for decades. "He's always been looking out for others, a real hero and valuable role model."

Kirk neither boasts about his war service nor complains about the thrice-weekly kidney dialysis treatments he's endured for years.

"You had to pull out his stories about the Battle of the Bulge," Khaliq said. "His mind is still sharp and when he tells you something, you can take it to the bank."

Kirk said his northern upbringing left him unprepared for the racism he met in Texas during basic training.

"All of a sudden, we couldn't use the same drinking fountains or go to the same movie theaters as Caucasians," he said. He recalled a train conductor pointing him to a "Jim Crow" railcar, where he was stood in a smoky car behind the engine despite a handful of half-empty passenger cars.

He met fellow Black enlistees in the Army from the Deep South, "grandchildren of slaves" who came from cotton fields and couldn't read their names if they were in neon lights, he said. He taught them what he could and showed them where to sign documents with an X.

"I've always marveled at how African Americans aren't just mad as hell," said the Rev. Grant Abbott, a retired pastor who counted Kirk among his parishioners at Holy Trinity Episcopal Church in St. Paul's Hamline-Midway area.

"Gordon has managed to keep his humanity despite all he's been through," Abbott said. "He's stayed true to himself."

Curt Brown's tales about Minnesota's history appear every other Sunday. Readers can send him ideas and suggestions at mnhistory@startribune.com. His latest book looks at 1918 Minnesota, when flu, war and fires converged: strib.mn/MN1918.

Minnesota History: Ad man turned Paul Bunyan into a folklore icon

Minnesota History: James Griffin used persistence to blaze a trail for St. Paul's Black police officers

Minnesota History: For Granite Falls doctor who tested thousands of kids for TB, new recognition is long overdue

Minnesota History: A New Ulm baker wearing a blanket fell to friendly fire in the U.S.-Dakota War