How much flour would it take to turn Lake Superior into bread?

Listen and subscribe to our podcast: Apple Podcasts | Spotify

Elodie Yerich took on a lot of the dough-based food duties during her second trip to the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness with the YMCA's Camp Menogyn this past summer.

She made pizza crust, blueberry pie, gnocchi and cinnamon rolls for her fellow teenaged campers during the nine-day trip — using her water bottle to roll out the dough on the back of a canoe. There was a theme to her makeshift kitchen vistas.

"Whenever I was making it, I was next to a lake," said Yerich, a freshman at Mounds View High School.

Surrounded by so much water, Yerich, 14, started to wonder: How much flour would it take to turn Lake Superior into a loaf of bread?

Yerich submitted her question on Curious Minnesota Day at the Star Tribune's State Fair booth during the fair. And it was a hit. Fairgoers voting on their favorite questions overwhelmingly picked it to be answered by the Star Tribune's reader-driven community reporting project.

Lake Superior is the largest of the Great Lakes — and the deepest. It has the biggest surface area of any freshwater lake in the world, at 31,700 square miles. It is 483 feet deep, on average, and drops to 1,332 feet at its deepest point.

So the Lake Superior Loaf is no small undertaking.

Flour power

In Duluth, one of Lake Superior's major port cities, the best place to go for a hypothetical baking question (that would benefit from the use of a graphing calculator) is Duluth's Best Bread. The European-style bakery is owned by the dry-humored, Duluth-raised 30-something brothers Michael and Robert Lillegard.

"Anything for a joke," explained Michael, a math major-turned-baker who once baked a 17-pound pretzel.

For the purposes of baking Lake Superior Loaf, the most significant statistic is that the lake has a volume of about 2,935 cubic miles, according to the Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory.

Michael, who recently watched a documentary about Mount St. Helens in Washington State, is quick to put this into context. A single cubic mile of rock was blown from Mount St. Helens during the devastating 1980 eruption, decreasing the size of the volcano by 12%.

"Oh, wow," Robert said, putting the lake's volume into perspective. "This is 3,000 Mount St. Helens explosions."

A Duluth's Best Bread-specific caveat: This particular bakery creates bread with an 80% hydration level — which is the percentage of liquid used in relation to the amount of flour used. That is wetter than normal. The average bread has a 60% hydration level. Since this is this bakery's response to how to make Lake Superior Loaf, they are operating with their numbers. Their loaf, their recipe.

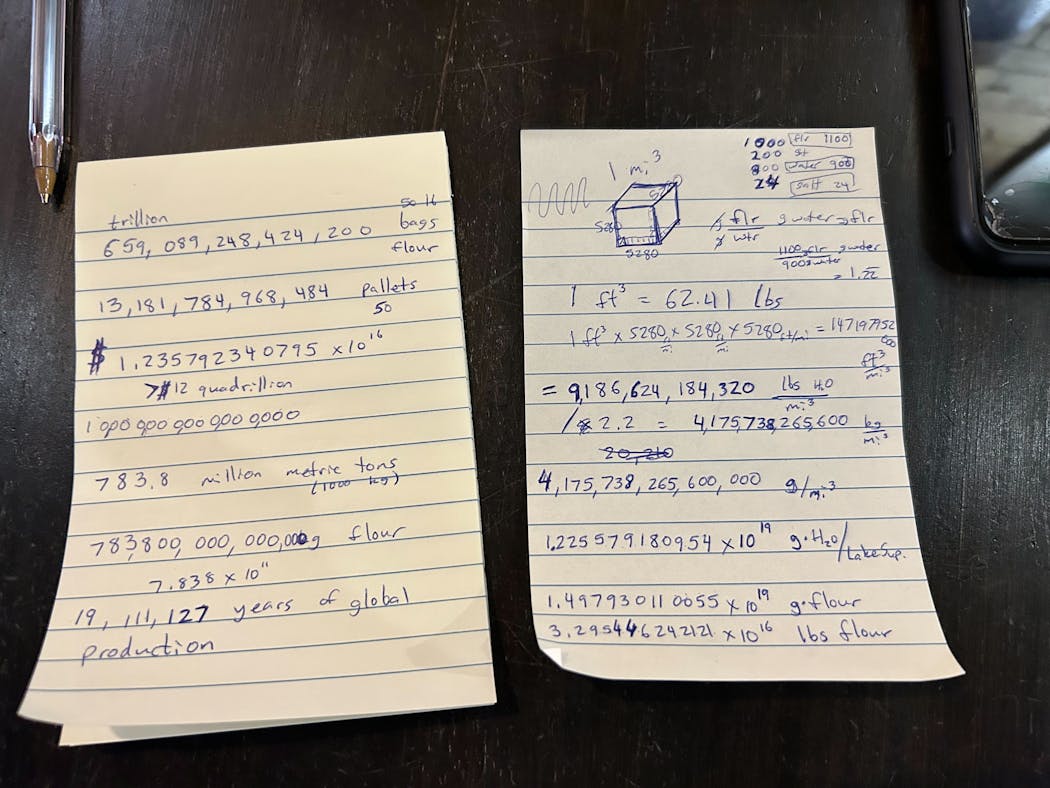

To perform the calculation, Michael sketched out a cube, shaded in squares and went back and forth between his phone's calculator app and yellow scratch paper. The answer to Yerich's question: about 33 quadrillion pounds of flour — or 659 trillion-gallon bags of it.

Purchasing this much flour would cost them more than $12 quadrillion, which Michael was sure would qualify for a discount from his contact at BakeMark.

A baking feat

If this flour were added to Lake Superior, the resulting loaf would be seasoned with the rusted remains of about 350 shipwrecks, including the famous Edmund Fitzgerald and some that have yet to be discovered. But it's clean. Ten percent of the world's freshwater comes from this lake, which has a largely undeveloped shoreline.

While Michael made calculations, Robert considered the side issues of baking a loaf of this size. He first considered using a volcano to bake it (à la Mount St. Helens), but quickly discarded that idea in favor of digging into the Earth's crust until hitting the optimal baking temperature of 450 degrees. This is nearly 5.5 miles below the surface.

But then what?

"We'd have to get it out somehow," Robert realized.

"It's still going to turn out kind of weird," Michael said. "It's probably going to be burnt around the edges."

Keeping the dough from rising too much will help keep it from browning too quickly. It would bake more evenly if it was shaped into a ring, a pretzel, small loaves or into a curved sine wave, the Lillegards said.

Another hiccup: Changes in temperature can affect the volume of water. With cold water, the dough won't be as sticky, but it's going to take a long time to rise. Michael proposed combining the ingredients in a long trough. Perhaps a train could drive over the flour trough and dump water, he wondered, or vice versa.

It's a moot point, Michael said. There had long been a bigger issue nagging at the back of his mind: The availability of resources.

"I'm not sure if there is enough flour in the world to make it," he said.

He's right. There isn't.

The world produced enough wheat to make just over one trillion pounds of flour last year, based on a Star Tribune analysis of USDA data. That's not even .01% of what's needed for the loaf.

And even if there were enough flour right now, the world economy falls far short of the price tag for baking this loaf.

"It's not even close," Michael said.

During a recent phone call, Yerich paused to take in the amount of flour required to make the Lake Superior Loaf.

"You mean my Lake Superior bread dreams aren't realistic?" she said, and laughed.

Still, Yerich said, she could make this her life's work. But she also noticed a side dilemma that no one had yet considered.

"I'd need to find a textile place to make a damp towel big enough to cover it," she said.

If you'd like to submit a Curious Minnesota question, fill out the form below:

Read more Curious Minnesota stories:

What is the largest machine in Minnesota?

Is Duluth the most inland seaport in North America?

How do Minnesota lakes get their names?

Why does Minnesota sometimes get colder than the North Pole?

Was Duluth once home to more millionaires per capita than any other U.S. city?

Why isn't Isle Royale a part of Minnesota?