Barnett "Bud" Rosenfield, a prominent attorney who championed the rights of people with disabilities, and whose tireless legal advocacy eliminated barriers to inclusion for thousands of Minnesotans, has died of a heart attack at the age of 57.

Orphaned at an early age, Rosenfield overcame childhood tragedy to become one of the state's foremost leaders of the disability rights movement. Over a trailblazing career spanning three decades, he was instrumental in winning a spate of major legal advances for Minnesotans with disabilities, enabling them to enjoy freedoms that many able-bodied people take for granted.

"Bud worked long and hard for people's freedom so they could participate in society and have agency over their lives," said Anne Henry, a retired attorney at the Minnesota Disability Law Center, reflecting on Rosenfield's death last month. "He had brilliant legal skills, but he combined that with a tenacious commitment and compassion for his clients."

Rosenfield, a Boston-area native, spent the final year and a half of his life as the state ombudsman for mental health and developmental disabilities, though he is most known for his forceful and articulate legal advocacy. He played a pivotal role in a landmark 2016 civil rights case that accused the state of mismanaging more than $1 billion in Medicaid funds, forcing thousands of Minnesotans with disabilities to languish for months or even years on waiting lists for services that would have enabled them to live more independently in the community. The case roused public outrage and ultimately galvanized the state to eliminate the long-standing waiting lists.

Rosenfield also represented clients in a large-scale lawsuit alleging that people with disabilities were not getting the help they needed from the state to move into homes or apartments of their own, and instead were steered into four-bedroom group homes, where their everyday decisions were often carefully controlled. The multi-year legal fight led to a major legal settlement last summer, in which the Minnesota Department of Human Services (DHS) agreed to expand access to independent housing for approximately 13,000 Minnesotans in group homes.

Rosenfield's unwavering dedication to the less fortunate stemmed from his childhood experiences growing up with an older brother with an intellectual disability.

He was the youngest of six children born to a middle-class family in Chelsea, Mass., a suburb of Boston. His mother, Lorraine, a nurse and homemaker, died of a brain injury when he was 9; and his father, Jace, a dentist, died four years later from complications related to early Alzheimer's disease. After his mother's death, Rosenfield and two of his siblings moved in with their aunt, Bonne Jean Johnson, who moved the children to Silver Spring, Md.

At an early age, Rosenfield developed a lasting bond with his brother, Paul, who was four years older and had Down syndrome. When Bud would go to music concerts or sporting events in high school, he would insist on his brother joining them. The siblings were often seen zipping around the neighborhood on their bikes, with Paul frequently not far behind his brother.

"Bud's rule was, 'Either Paul's included, or I'm not going,' " said Rosenfield's wife, Barbara Fipp. She recalled him saying: "It was both of us or nobody."

Later, when Paul moved into a residential home in Maryland for adults with disabilities, Rosenfield continued to advocate on behalf of his brother and pushed to ensure that he was treated with dignity. On visits and Zoom calls, Rosenfield insisted his brother be given the same control over everyday choices as people without disabilities who live on their own.

"Bud would say, 'Paul likes pizza. How many times a week is he getting pizza?' 'He likes baseball. Is he going to baseball games?'" said his sister, Dr. Cathy Rosenfield, who lives near Boston. "Those things were really important to Paul's quality of life."

Rosenfield would bring a similar intensity to advocating for clients at the state Disability Law Center, where he worked for 25 years.

Robin Anderson credits Rosenfield with rescuing her son from a life-threatening living environment. Her son, Christopher Harmon, had a rare neurological condition that made it impossible for him to speak, see or move about on his own. When Hennepin County denied him a request for sign language services, Harmon was trapped inside his body — unable to tell his group home staff when he was hungry, thirsty or in pain. Rosenfield stepped in, and after an 18-month court battle, Harmon became the first deaf-blind person in Minnesota to win full-time interpreter services.

"Bud was an absolute gift from God," said Anderson, who lives in La Crosse, Wis. "There was no way that my son could have survived very long, just lying there in his bed with no stimulation and no way communicate."

In addition to his wife, Rosenfield is survived by his two children Hannah Fipp-Rosenfield, 27, and Jace Fipp-Rosenfield, 24; his siblings Keith, Paul, Cathy, Mary Lynne and Rikkie; and numerous nieces and nephews.

Services have been held.

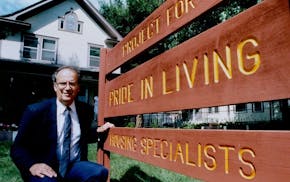

Joe Selvaggio, social change agent who started Project for Pride in Living, dies at 87

Bemidji State University women's volleyball coach dies of cancer at age 41

Former Minnesota veterans commissioner, who resigned after ALS diagnosis, dies at 61

Axel Steuer, who guided Gustavus Adolphus College through 1998 tornado, dies at 81