TOKYO — President Joe Biden on Wednesday is expected to issue an executive order aimed at reforming federal policing on the two-year anniversary of the death of George Floyd, who died after being handcuffed and pinned to the ground by a Minneapolis police officer, people familiar with the matter said.

The order will direct all federal agencies to revise their use-of-force policies, create a national registry of officers fired for misconduct, use grants to encourage state and local police to tighten restrictions on chokeholds and no-knock warrants, and restrict the transfer of most military equipment to law enforcement agencies, the people said. They asked for anonymity to discuss the details of the order before it is announced.

The White House and the Justice Department have been working on the order since last year, when efforts to strike a bipartisan compromise on a national policing overhaul failed in the Senate. Biden's executive order is expected to be more limited than that bill, a sign of the balancing act the president is trying to navigate on criminal justice.

While the death of Floyd and the national protest movement it inspired helped drastically shift public opinion on matters of race and policing in summer 2020, Republicans have also launched political attacks that portray Democrats as the enemies of law enforcement.

The order is unlikely to please either side entirely; many progressive activists still want stronger limits and accountability measures for the police even as a rise in violent crime in some cities has become a Republican attack line heading into the midterm elections.

But officials believe the order, whose final text has been closely held after the leak of an earlier draft early this year, will get some support from both activists and police.

Biden plans to sign the new executive order, alongside relatives of Floyd and police officials, in what is expected to be among his first official acts after he returns from a diplomatic trip to South Korea and Japan this week.

Police groups had been particularly upset by several items in the earlier 18-page draft order when it became public in January, leading them to complain that the White House had given them only a perfunctory chance at input. They threatened to pull their support, leading to a major reset in the process by the White House's domestic policy council, led by Susan Rice.

In the months since, the White House has worked more closely with police and Justice Department officials, who have greater experience straddling the line between police reform and running law enforcement agencies, as the administration has elevated a more centrist position on criminal justice.

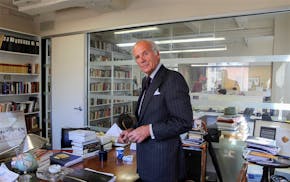

"The White House did significant outreach with us and tried to listen to our concerns, said Chuck Wexler, executive director of the Police Executive Research Forum, a bipartisan think tank that focuses on police practices. "This final executive order is substantively different from the original version, and that's made a big difference to many of us in law enforcement."

Biden has repeatedly emphasized a message of investing in, rather than defunding, the police — wading into a national debate about whether the government should give police departments more resources or spend the money on mental health care and other social services instead.

One of the changes reflected in the executive order, according to the people familiar with the final version, centered on what it would say about standards for using force.

The administration has taken out language that would have allowed federal law enforcement agents to use deadly force only "as a last resort when there is no reasonable alternative, in other words only when necessary to prevent imminent and serious bodily injury or death." The earlier version would also have encouraged state and local police to adopt the same standard using federal discretionary grants.

Law enforcement officials complained that the standard would allow second-guessing in hindsight of decisions by officers in exigent circumstances. The final order instead refers to a Justice Department policy issued this week that says officers may shoot suspects when they have "a reasonable belief that the subject of such force poses an imminent danger of death or serious physical injury to the officer or to another person."

Jim Pasco, executive director of the Fraternal Order of Police, said he thought new use-of-force language would "bring more clarity and better guidance to officers" but without causing them to become so risk-averse that they fail to protect themselves and others when necessary.

"It's not a question of stricter or less strict," Pasco said. "It's a question of better framed. And a better-constructed definition of the use of force."

He added, "It's not a sea change."

Udi Ofer, deputy national political director of the American Civil Liberties Union, offered cautious support for the Justice Department policy, saying much would depend on how it was carried out.

"Correct implementation of this standard will be pivotal for its success," he said. "We have seen jurisdictions with strong standards where officers still resort to the use of deadly force, so just having these words on paper will not be enough. The entire culture and mentality needs to change to bring these words to life and to save lives."

The administration will also include guidance on screening inherent bias among the rank and file, including those potentially harboring white supremacist views, according to people familiar with the matter.

Some provisions in the order would build off previous efforts by the Justice Department, including mandating that federal law enforcement agents wear body cameras. The order would also direct the government to expand data collection, including use-of-force incidents across the country, and would attempt to standardize and improve credentialing of police agencies.

JD Vance, an unlikely friendship and why it ended

Lewis Lapham, editor who revived Harper's magazine, dies at 89

Body of missing Minnesota hiker recovered in Beartooth Mountains of Montana

Mike Lindell and the other voting machine conspiracy theorists are still at it