“Jeez, who’s the masochist who put this together?” quipped Tim Torgerson, one of three cyclists in our group.

It wasn’t a question so much as gallows humor, and Dan Winga and I managed smiles in our collective suffering.

In every direction, upland farms and homes and verdant cropland filled our view from our high spot. The southeastern Minnesota vista seemed without end — a lot like the hills we’d climbed over the last four hours.

Our bike ride was unlike anything the three of us had experienced on wheels. Well, if you don’t count the previous two days.

The three-day bikepacking trip took Bob Timmons, Dan Winga and Tim Torgerson, from left, through a variety of landscapes, including a bridge above Bear Creek in Fillmore County, rural farmland with inquisitive cattle, and the Preston library.

For years we have propelled our road bikes over pavement or mountain-biked, but this outing was cycling encountered in a new way, testing our boundaries physically and mentally. For us, a bold test.

We were carrying our gear — bikepacking — on a point-to-point ride to state parks and mainly on gravel backroads in parts of the Driftless Area, aka Bluff Country. Combined, it seemed we were checking all the boxes for adventure.

Day one

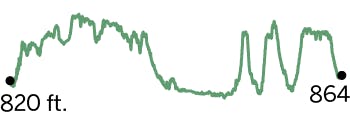

80.4 miles

7:40:50 moving time

4,881 feet in elevation

Day two

63.8 miles

7:06:48 moving time

4,534 feet in elevation

Day three

52.8 miles

5:07:39 moving time

3,590 feet in elevation

Bikepacking essentially is backpacking on wheels. Carry what you need. Be self-sufficient. What separates bikepacking from bike touring is where it happens: off-road.

Bikepacking and gravel riding are increasingly popular in Minnesota, where opportunities abound. Both, too, are born of a recreation truth: Cyclists — like anglers, hunters, trail runners and others with a thirst for recreation — are seekers. They break ground on new ways to do things.

As gravel riding has swelled in recent years, sales of gravel bikes — with larger tires and longer wheelbases that better absorb rocky roads — have increased. The allure of back-roads riding is twofold: freedom and safety. Following close to a route used by other riders that ensured solitude and exploration, Tim, Dan and I reveled in long stretches with nary a vehicle in sight.

After a day on the saddle, we hunkered down in state park camper cabins. That way we were less encumbered with gear like tents, sleeping bags and pads. We kept our bedding light (blanket, camping pillow). Tim carried a small jet fuel stove — the lightweight backpacker’s stove of choice — to boil water for oatmeal and coffee. We stuffed bags and shirt pockets with electrolyte tabs for water bottles, energy bars, Salted Nut Rolls, bananas and other quick calories. As quickly as we burned through these supplies, we refueled at convenience stores, park pumps, cafes and public buildings.

Along the way, we rode under a hard summer sun for hours; we played chance with lightning before finding refuge; we took dust baths in the wakes of passing vehicles; we slalomed and fish-tailed down miles-long slopes; and we climbed plateaus past rocky ledges that were on-ramps for even harsher avenues of pain.

After long days of riding, the group stayed in state park camper cabins, which ensured they wouldn't be weighed down with gear like tents, sleeping bags and pads.

Within a mile or so, we took a hard left up off Hwy. 74, which bisects the park, over a fork of the Whitewater River. The river takes its name from the Dakota word minneiska. We were on Old Glory Road. How fitting, I thought, for the three of us, aged 56 and above, trying to keep our fire for the outdoors burning.

Old Glory took us uphill, immersing us in Whitewater’s striking maples and woodlands. The view was exhilarating — here we go! — and daunting.

Our first 10 miles or so were a crash course in the next days to come — gravel, hills, valleys, remote beauty and a lot of sweat equity — and we descended into St. Charles and stopped at Del’s Cafe to top off our tanks.

We missed the breakfast regulars by an hour or two, which our brassy waitress reminded us when I asked whether many cyclists stop to feast on the buttery hashbrowns, pancakes and eggs.

“Psychos?” she shot back with humor. “Some of them were here earlier.”

Perhaps Tim, Dan and I were the ones who needed our heads checked. But we relished the opportunity to see what the next miles would reveal.

We could have picked no better terrain than rural Winona, Fillmore, Houston and Olmsted counties, which are a gravel rider’s dreamscape. The Driftless is a geologic phenomenon, so named because it was only thinly covered by glacial drift. Largely lakeless, it’s veined by moving water. Within our first hours, we crossed Pine, Money and Big Springs creeks as we sliced through ravines on our way to a break in Rushford. Hard along the Root River, the city takes its name from Rush Creek.

We had three dramatic uphills that were almost ridiculously steep and lengthy in our final 40 miles of the day. All we could do is look skyward as we muscled our way up and up still farther, in silent competition with the hills. Of course, what goes up must come down, and we were given a 2-mile descent into Beaver Creek Valley, its quiet beauty and the sanctuary of our state park cabin bunks.

The afternoon of June 28 brought a thunderstorm that the trio pedaled into on their way to Forestville State Park. They eventually took cover at a home in Carimona Township and checked the radar to see when it would pass.

“It is an intimate geography,” wrote conservation biologist Curt Meine in The Driftless Reader. “It can be a landscape of comfort and contentment; yet its coulees can also seem narrow and confining. … It is neither ‘pristine’ nor wholly humanized. It holds within it the wild and the cultivated.”

Ever-present as we pedaled through cities, villages and townships over the three days was a sense of the region’s pioneer history. Peterson. Sheldon. Black Hammer. Yucatan. Fillmore. Settlements born of the mid-19th century, some of their better times are recalled today by buildings scarred by weather, misfortune and time.

For Tim, who grew up on a dairy farm in Kenyon, the scene gave our travel a keener resonance. Dan also deepened his appreciation for an area that mirrors his own history — he grew up in the coulees of La Crosse, Wis.

Near day’s end, we left a shady spot in downtown Preston, about 9 miles from Forestville. The heat had been unrelenting and the mercury was still in the 80s. Climbing onto a long, wide plain beneath angry gray skies to the southwest, our heads were down and the wind was up. Then the rain came.

The atmosphere was electric. Too electric. Lightning diverted us into the safety of an open garage, its young owner was working on his four-wheeler. He dropped his tools and welcomed us, and for the next 20 minutes impressed us with his fishing and hunting stories and his knowledge and history of the area. His chocolate Labrador retriever, Forest, weeks-old, kept things light, too.

We eventually entered Forestville’s northeast corner and pedaled past a historic brick store — the Thomas Meighen store — a marker of the area’s enterprising beginnings. In our park cabin, we devoured sandwiches and salads bought in Preston, and boiled water for macaroni and cheese. We showered quickly and retreated to our bunks. Sleep came fast.

The three friends pedaled down a gravel road as they made their way to Forestville/Mystery Cave State Park after their second day of riding.

Our final day opened in a veil of fog, draping the park’s dense hardwoods near us in vapor — and the moment in metaphor. Whatever lay ahead, whether the journey’s successful completion or something less, was unseen.

In time the fog yielded to penetrating sunshine, revealing early spring corn coming fast, tidy farmhouses and curious livestock spooked by strange intruders, moving with speed.

The trip had been fun, yes, I could assure Katie of that when I returned home.

But even more so I was grateful for this adventure with Tim and Dan, in what now felt like more than just three days.

We had burrowed into the heartland in a way that was both old-school and up-to-the-minute — on bikes that were not only good tools to venture into these places, but perhaps the best ones.

Some Minnesotans hike. Others bird-watch, fish or hunt. Some like to turn wheels on gravel, over backroads.

Others still do all of these, and more.

In these pursuits, they learn something about where they live, and about themselves.

Our bikepacking odyssey achieved both.

“We all have seen this country before, but on bikes, over gravel, there was a newness about it,” Dan said.

“As hard as [the trip] was,” Tim added, “the fun part came because it was intense, and because of the relationships with the people you are with. You are in this together.”

The trip's final day opened in a veil of fog. Here the cyclists climbed a hill past Forestville Cemetery.