“Sadly, I thought wrong that law enforcement was there to help me and my family to de-escalate a situation that did not have to turn deadly.”

ChaMee Vue, daughter of Chiasher Fong Vue, 52. In December 2019, Minneapolis police killed her father after officers say he pointed a “long gun” at them. Vue says she hasn’t been allowed to see the body-camera video and is still searching for answers as to how a call for help ended in tragedy.

“They are corrupt, racist, and unwilling to change.”

Ashley Quiñones, wife of Brian Quiñones, a 30-year-old rapper killed by Edina and Richfield police after a car chase in 2019. The officers open fired on Brian after he got out of the car with a knife. Ashley says he posed no real danger to the officers and criticized a lack of transparency during the investigation.

Ding …

In early August, a week after the meeting in the park, Dimock awoke to the sound of a text message. It was early, not quite time to rise for work, so she ignored it, rolled back over to sleep a little longer with her Chihuahua, Lettie.

Ding … Ding … Ding …

More messages poured in. She knew something had happened. She answered a call from Jason Heisler, her ex-husband and Kobe’s father. As she listened to his news, she noticed she was not mad, not sad — not really anything.

She walked into the living room and relayed the message to Encarnacion Garcia, her partner of 20 years, who was on the couch watching television.

“They’re not charging,” she said.

Garcia, who was both mad and sad, uttered an expletive. “What are we going to do?” he asked.

Dimock is a wiry 47-year-old with short black hair and a bright smile. Fifteen years ago, she broke her back as the passenger in a car wreck that doctors said would leave her permanently paralyzed. Dimock regained her leg function, though she still walks with a limp and she sometimes uses a cane, the latter mostly serving as a warning to give her space in crowds. She lives in Baxter, Minn., a rural town in a conservative part of the state, in a house on a lake with an American flag glimmering in the front yard, where she is among the less than 1% of residents who are Black.

Dimock is a self-professed introvert. Even before the pandemic, she left her 8-acre property as infrequently as possible. She never pictured herself speaking at protest rallies or on TV news or fielding personal calls from the governor.

In August, after the Hennepin County Attorney’s Office declined to charge the officers who killed her son, Dimock held an impromptu news conference in front of the government center to call for an independent investigation into her son’s killing. There, she cried for the first time about the decision.

By the time she got the call that Hennepin County Attorney Mike Freeman’s office would not file charges, it had been 11 months and five days since two Brooklyn Center police officers killed her son.

Kobe had lost his temper at Wendy’s and his grandfather, Erwin, left him to walk the six blocks home. Erwin thought the walk would cool him off, but instead it had the opposite effect. Kobe stormed into the house and grabbed a paring knife and a hammer and demanded an apology.

Kobe had recently lost his health insurance, leading him to go off his medication and quit a treatment program. He had never hurt his grandparents before, but earlier that year, during a similar episode, he’d cut himself with a kitchen knife and been committed to the hospital on a psychiatric hold. Erwin feared Kobe may hurt himself again and called 911.

In interviews with investigators later, Erwin said Kobe’s demeanor changed abruptly when he found out the police were coming. “He was just crying. He was so upset that the police were going to come, take him away and commit him.” Erwin took the weapons from Kobe and called back 911 to tell them to “just forget it.” The officers arrived anyway. Erwin asked them not to come inside the house, but they insisted on making sure everyone was OK. Police body camera footage shows Kobe seated in the living room, holding his head in his hands and sobbing as the officers questioned him. Then, suddenly, he lunged for something hidden in the couch cushions.

“He’s got a knife!” screamed one of the officers.

And then they shot him six times.

For a long time afterward, Dimock thought the officers would be held criminally liable for shooting her son. When months passed, and summer turned to winter and then spring, she thought maybe Freeman’s office was just taking time to build a rock-solid case.

Then George Floyd died. Watching the national news, she saw celebrities, reporters, presidential candidates — everyone — speaking Floyd’s name.

“Why aren’t you saying ‘Kobe Heisler’?” she wondered. “Why is my son’s name not in your mouth also?”

After that, Dimock and Garcia started driving down to Minneapolis for protests. There, they met the other families whose stories were similar to her own. Like Dimock, they too had waited for justice that never came.

When Freeman made the official announcement not to charge, if she felt anything at all, it was a relief to have that part over with. At least now she could take the next steps, like pursuing a civil lawsuit.

Dimock decided to hold a news conference that day outside the government center in Minneapolis, where Freeman’s office is located, to call for an independent prosecutor to review the case. She cried for the first time just after 3 p.m., standing in front of hundreds of people, including the other families and a dozen TV cameras.

That night, before driving back to Baxter, Dimock attended another protest. It was a small but vigorous crowd. Instead of shouting “shut it down,” they were screaming “burn it down.” At one point, a squad car drove by and the protesters swarmed it, yelling expletives at the officers inside.

This wasn’t Dimock’s style. She and Garcia have law enforcement in their families, and she knows police are not all bad people. But that night she found herself flipping the middle finger to the police officers.

“Get a different job!” she shouted. “What’s wrong with you?!”

“Out of all of the murders here in Minnesota at the hands of law enforcement, there is only one family that is currently living to see justice.”

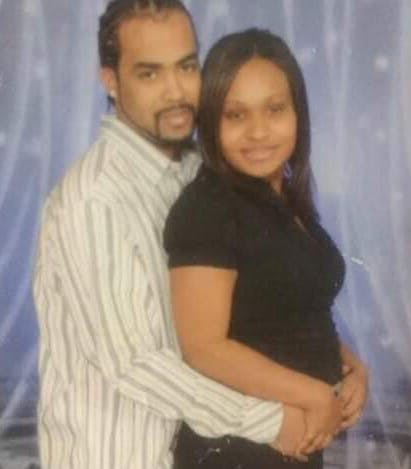

Toshira Garraway, founder of Families Supporting Families Against Police Violence, shown here with her fiance, Justin Teigen. In August 2009, Justin, 24, was found dead in a recycling facility after a chase with St. Paul police. Police say he crashed his car, climbed into a dumpster and suffocated when the truck picked it up. Garraway believes police are responsible for his death.

“Police officers in Minnesota are not trained well in de-escalation. If they were, Travis would be alive today.”

Taren Vang, girlfriend of 36-year-old Travis Jordan, killed by Minneapolis police in November 2018. Vang, fearing Travis might hurt himself, called for help, and when police responded, he walked toward them with a knife. Travis’ family and friends say he didn’t have to die that day.

In the world of the families, birthdays and death anniversaries are sacred, so they held a rally across the street from the Fourth Precinct, the north Minneapolis police headquarters, on the day Travis Jordan would have turned 38 years old.

Police shot and killed Jordan in November 2018. His girlfriend had called for a wellness check, afraid he might follow through on a threat to hurt himself. When the officers arrived, Jordan was holding a knife. He walked toward them, screaming, “Let’s do this!” The whole thing took less than two minutes.

Freeman said that Jordan presented a serious threat, and the officers were justified in using deadly force. Yet Jordan’s friends and family say it could have gone differently, that someone could have talked him down, that the officers could have kept a barrier between them and Jordan so they didn’t need to shoot.

“Travis had one bad day,” said Paul Johnson, Jordan’s best friend and roommate. “He could have easily recovered from that bad day. Easily.”

Now, nearly two years later, outside the police precinct where the officers who shot him work, the crowd sang “Happy Birthday” to Jordan. Then the families spoke.

Youa Vang Lee told of how a police officer from this same precinct shot her son, Fong Lee, on a playground 14 years ago. “He was out playing sports when the police approached him and killed him,” she said through a translator.

The officer who shot him eight times, Jason Andersen, said Lee had been carrying a gun. Lee’s family argued the gun was planted and had been in a police evidence locker for two years. A federal jury ruled that Andersen used reasonable force, and after the police chief fired him, Andersen fought the discharge through arbitration and won his job back with back pay. He was also charged criminally and fired for kicking a teenager in the head; in 2010, a jury found him not guilty and he again got his job back. He still works for the Minneapolis Police Department.

The families’ stories vary greatly in key details, such as whether their loved one carried a weapon, or if the incident was caught on film. Many begin with a person in the mental health crisis, which is why the families believe more 911 calls should be handled by social workers instead of armed police officers.

‘I just miss him so much’

After police killed her son, Amity Dimock began pushing for systemic change to law enforcement in Minnesota.

ChaMee Vue is among those who don’t know what happened during their family members’ final moments. She connected with the families in hopes they could help her find answers. Her father, Chiasher Fong Vue, was killed last December by Minneapolis police, and Vue said her family still hasn’t been allowed to view the body-camera footage.

“My dad was shot at by more than 100 bullets,” she said outside the Jordan rally. “He was killed by 13 bullets.”

Many of the families talk about how the system makes it difficult to find answers after these tragic encounters. Dimock was not permitted to see bodycam footage of Kobe’s death until the week Floyd died — nine months later — when the Brooklyn Center mayor invited her to come to his office and watch it, she presumes in hopes of stopping riots from spreading to his city.

Dimock has asked legislators to pursue a new law that would require police to show blood relatives bodycam video within 48 hours of the death. The families also want to end qualified immunity, the legal principle that protects police from being sued if they’re acting within their duties. They want to set up a system that allows them to seek reparations, and to eliminate the statute of limitations that stops some families from getting justice in civil courts years later. And they want to pressure prosecutors to more aggressively pursue charges against law enforcement officers who use deadly force or otherwise cause the death of a person in their custody.

Del Shea Perry, also present at the Jordan rally, spent two years calling for an investigation into how her son, Hardel Sherrell, died in Beltrami County jail. This summer, Department of Corrections Commissioner Paul Schnell joined her in demanding an investigation, after jail employees discovered two misfiled letters written by medical staff shortly after his death. In Sherrell’s final days, the letters state, guards neglected his complaints about his diminishing condition and “spoke negatively” of him, including accusing him of faking the paralysis that had spread throughout his body. The letters state the guards left Sherrell in his cell in soiled clothes and a diaper, which they refused to change, before he died of an undiagnosed immune disorder on Sept. 2, 2018.

Dimock touched her son’s urn, which rests on a table in her kitchen surrounded by clothes, art projects and other keepsakes that belonged to Kobe. The family spread a portion of his ashes in the Mississippi River during a Viking-style funeral ceremony.

A few weeks after the Jordan rally, in late August, some of the families marched through Minneapolis with Mia Montgomery, whose father, Lionel Lewis, died in Hibbing after police arrested him in 2002. Lewis’ death certificate lists the cause as “agitated delirium” — a controversial diagnosis that often entails profuse sweating, aggressive behavior and hyperthermia — and cocaine use. The day of the march, it was Montgomery’s birthday, and hundreds of people showed up to walk with her to Father Hennepin Bluff Park, where they grilled dinner and held a memorial for her dad.

Across the river, a crowd gathered around Nicollet Mall, where some said a police officer had killed a man. The crowd did not believe the police, who said the man had killed himself. By the time police released a video showing the death was actually a suicide, it was too late. By nightfall, rioters were breaking windows and looting shops downtown.

All over the country, from New York City to Los Angeles, similar protests and riots were unfolding over the police shooting of Jacob Blake, an unarmed Black man in Kenosha, Wis.

“To reform the criminal justice system you have to change the laws that were made to oppress.”

Matilda Smith, mother of Jaffort Smith, 33, killed by police in May 2016 after officers say he ignored orders to drop a firearm.

“The laws are broken by police violence. They are sworn to serve and protect but they're murdering innocent children ... What's right about that?”

Marilyn Hill, mother of Demetrius A. Hill, 18, killed by St. Paul police in April 1997. Hill says she doesn’t believe officer accounts that her son pointed a gun at them. She only began talking about the death this summer, 23 years later, in the aftermath of the Floyd killing, when she met the other families.

“They have been doing business their way, and it's not been fair to people of brown and black skin. It's time for a change, and we must work together to make that change become a reality.”

Del Shea Perry, mother of Hardel Sherrell, 27, who died from an undiagnosed immune disorder in Beltrami County jail in 2018. Medical staff at the jail say guards ignored Hardel’s complaints of chest pains and paralysis, and left him on the floor of his cell in a soiled diaper.

On Aug. 31, exactly one year after her son’s death, Dimock stood in front of a crowd of about 200 people outside Hennepin County Government Center in downtown Minneapolis, alongside five other women who have lost family members to law enforcement encounters.

The plan had been to march through downtown. But after the riots the week before, which Dimock did not want to see repeated, she asked the others to limit the event to a candlelight vigil.

The last few months have taken a toll on Dimock. She will continue to work behind the scenes to promote change. She may move to Minneapolis and run for office. She is considering turning her Baxter property into a retreat center for families who have lost people to police violence. But she’s decided her time driving down to Minneapolis, often several times a week and requiring her to miss work, must come to an end.

When it was her time to speak, she found the words stuck in her throat, making her choke up. She leaned on her cane for support as she tried to force them out. “The last time I saw my beautiful boy, he was lying in the morgue. He was still hard from the ice. And cold and clammy. I’m still upset I didn’t take the wisp of hair that I saw — I wish I had it. I just want to see my boy again. I just miss him so much.”

As she climbed in the car afterward, five deputies in tan uniforms rushed outside the Government Center, lined up across the street, and stared at her car. One of them placed a hand on his belt, near where his gun was holstered.

“Hey, we’re going to get pulled over, man,” said Garcia as he drove off. “I see him radioing.”

“Oh my God. Oh my God,” said Dimock. “I do not like this.”

Garcia drove steadily, careful not to stray above the speed limit, his eyes darting at the rear view mirror, until they arrived safely at the corner of Park Avenue and S. 37th Street.

Just a few blocks from where Floyd died, there is a cemetery that runs about half the length of a football field, with the words “Say their names” written on a hill. The headstones hold names like Travis Jordan, Hardel Sherrell, Justin Teigen, Philando Castile, Thurman Blevins, Jamar Clark, Brian Quinones, George Floyd and Breonna Taylor. No one is actually buried here, and the headstones are made of flimsy cardboard. But for Dimock, this guerrilla art installation has become a holy place.

“Look at all these people,” said Dimock, walking through the memorial. “Isn’t this sad?”

She arrived at the headstone that said Kobe Heisler. It was decorated with photographs. The date of his death is wrong. But since Kobe’s ashes sit on a table in her kitchen, it’s the closest thing she has to a grave site.

“When I see this, I just see that he was clearly loved,” said Dimock.

Dimock, Garcia and a few family members cleaned up the headstone and rearranged the offerings, placing roses they brought from the vigil. They sat around the headstone and smoked cigarettes and talked until darkness shrouded the cemetery.

“It’s getting dark,” Garcia called to her. “I don’t like being out here after dark.”

Dimock lit one more cigarette and stuck around just a little longer.

Credits

Reporting Andy Mannix

Photography Aaron Lavinsky, David Joles

Photo editing Deb Pastner

Videography Aaron Lavinsky, Matt Gillmer

Video editing Jenni Pinkley

Editing Abby Simons, Catherine Preus, Eric Wieffering

Design Anna Boone, Josh Penrod

Development Anna Boone, Jamie Hutt