A chilly, rainy morning signaled Duluth's summer was fading on Aug. 22, 1894, when 7-year-old Guy Browning's mother sent him to fetch driftwood for the stove.

He headed up the harbor side of Minnesota Point — the narrow, 7-mile sandspit extending southeast from the ship canal — but sprinted home with word of a ghastly discovery.

Returning with his mother, Guy showed authorities where a woman's body was partially covered with driftwood, her bloodied head wrapped in a satin-lined cape. A heavy blood-stained oak stick lay nearby. The next morning's Duluth News Tribune declared: "Is All a Mystery."

In 2012, that headline caught the eye of Northfield's Jeffrey Sauve during an unrelated computer search through digital newspaper records when he was archivist at St. Olaf College.

"At my lunch break, as I ate my sandwich, I figured I could learn what happened in a few minutes," Sauve said.

Instead, a decade-long obsession began for Sauve, now 57 and a full-time writer, who hoped to bring attention to what he calls "a forgotten soul." He searched Lakewood Cemetery in Minneapolis for more than an hour to pinpoint the victim's unmarked grave, and he woke startled from recurring nightmares of a grasping hand reaching for him from the Lake Superior shallows.

Sauve is sleeping easier now that his true crime book, "Murder at Minnesota Point," is out.

Duluth's population had mushroomed nearly tenfold between 1880 and 1890 to 33,115, but the 1894 murder, Sauve writes, was "the first unknown female homicide within the city limits" and "transfixed the locals with a certain morbid curiosity."

After more than a week on public display at the morgue, the victim found on the beach remained unidentified. She had a charm bracelet on her right wrist, with six of the dozen charms engraved. A married couple who owned Acme Laundry, where the victim's clothes were washed before she was redressed for viewing, said her undergarments were "those of a good woman" — not what "sporting women" would wear.

"Her brown serge skirt and matching waist jacket suggested a person of good station," Sauve writes.

Police detective Bob Benson followed a hunch and headed to Minneapolis — figuring if nobody in Duluth could identify her, she might be from the big city. He ordered posters printed up but missed his Sept. 1 train because the printer was late. It turned out that train was nearly engulfed in the Hinckley fire that erupted that day, killing more than 400 people and shifting attention away from the murder mystery.

Benson's hunch was correct. He determined the victim was 32-year-old Lena Olson, a Minneapolis domestic worker whose parents had emigrated from Norway to Wisconsin in 1861, the year before her birth. Benson escorted Olson's younger sister Lizzie, a Lake Minnetonka house servant, to Duluth, where she viewed the exhumed body and confirmed her sister was the mysterious victim found on the beach two weeks earlier.

Sauve leads readers through a complex series of potential suspects and alias names as they surface and fade. Detectives believed they had found their man in New Orleans; when that didn't pan out, they checked out a jailed suspect in an Ohio river town on the West Virginia border. That lead "again proved to be a wild goose chase of mistaken identity," writes Sauve, detailing many of the 20 potential suspects.

(Spoiler alert: Quit reading now if you'd rather dive into the book and keep the mystery going.)

Minneapolis police detective John Courtney finally cracked the case in April 1896 — more than a year and a half after Olson's death — with the help of handwriting experts and a Minneapolis boardinghouse owner who had held onto a boarder's battered briefcase after he ducked out on his bill.

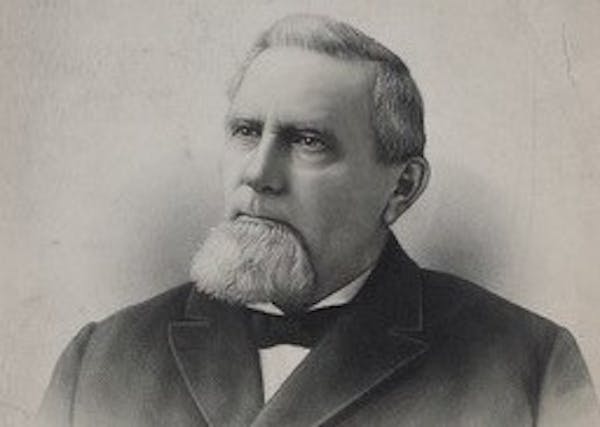

Inside the briefcase was a will with the name James E. Alsop, who juggled aliases and, Sauve says, "fancied himself a well-heeled Englishman" but was tangled in various real estate scams.

Courtney tracked down Alsop in Tacoma, Wash., and arrested him while the suspect was picking up his mail at the Seattle post office. Before he could be transferred to Duluth to face murder charges, however, Alsop hanged himself in jail with a noose crafted from his cell blanket.

"Lena was an easy target," Sauve said in an interview. "This guy who sounded like a rich Englishman offered to take her out of the drudgery of her domestic work, married her in Minneapolis and the next day knocked her off in Duluth for her $500 nest egg she'd socked away."

Now Sauve is raising money from book proceeds to finance a new headstone for Olson at Lakewood Cemetery in Minneapolis, where she was reburied in a pauper's section after her sister identified her.

Curt Brown's tales about Minnesota's history appear each Sunday. Readers can send him ideas and suggestions at mnhistory@startribune.com. His latest book looks at 1918 Minnesota, when flu, war and fires converged: strib.mn/MN1918.

Minnesota History: Ad man turned Paul Bunyan into a folklore icon

Minnesota History: James Griffin used persistence to blaze a trail for St. Paul's Black police officers

Minnesota History: For Granite Falls doctor who tested thousands of kids for TB, new recognition is long overdue

Minnesota History: A New Ulm baker wearing a blanket fell to friendly fire in the U.S.-Dakota War