Rena Pederson moved to Dallas in 1970 for her first reporting job. On one overnight shift, she saw a dispatch about a thief known as the King of Diamonds. In at least 40 burglaries over a decade, His Majesty had stolen several million dollars' worth of jewels from Dallas' elite.

He was brazen, often breaking in when the family was home. He'd climb up to a second-floor balcony, jimmy a door and walk into the victims' bedroom while they slept, find the jewelry and leave the way he came in.

Pederson's decision to investigate the crimes 50-plus years after they were committed is equally audacious. Even she concedes it was something of a fool's errand: "The trail was cold as a morgue. … Most of the victims and suspects were dead. And most of the records had been discarded."

Pederson interviewed more than 200 cops, victims and neighbors. The result is as much a sociological study of upper-crust Dallas society as a true crime story, enlivened by her sprightly writing style.

It was an interesting time, when the cattle barons and oil wildcatters were joined in the Texas billionaires club by financiers and corporate titans, all spending on lavish debutante balls, weddings and other entertainments. They had more money than they knew what to do with and a cavalier attitude. As one said: "After the first hundred million, who gives a damn?"

Despite police's best efforts, the thief continued to outfox and amaze them. One told Pederson it was virtually unprecedented for the thief to stay in one area as long as he did — given his climbing abilities, he was assumed to be a man — and not get caught. Usually "some detail trips them up, like a store receipt, a tool left behind, a footprint, a license plate — or an ex girlfriend."

There was a plethora of suspects. Because the thief knew the layout of the houses he burgled, knew where the jewelry was kept and didn't cause dogs to bark, suspicion centered on people who traveled in or near the same circles.

The Neiman Marcus jeweler who sold many of the items that were subsequently stolen was investigated. A hairdresser the socialites confided in was considered, as well. So were two ne'er-do-well brothers who'd worked their way into high society. The cops fingered one prominent local heir but were told to back off by the powers that be.

"King of Diamonds" is an enjoyable read, in large measure because of Pederson's extensive, high-quality research, obtaining compelling info from and about her subjects:

How James Ling (of Ling-Temco-Vought conglomerate) was upset that people thought he'd paid $25,000 for a bathtub — when he'd only paid $12,000.

Or the woman who was asked if she thought wearing her 48-carat ring was vulgar and responded, "I did — before I had one."

Pederson's lively style is a major plus. One woman "had the kind of looks that made a man ambitious." At one nightspot, "millionaires sipped Scotch older than their dates."

"When people look back on the King of Diamonds era, they don't remember the excesses — and inequalities — as much as they remember the great flair and style," Pederson concludes. Which is exactly the way she wrote this book.

Curt Schleier is a critic in New Jersey.

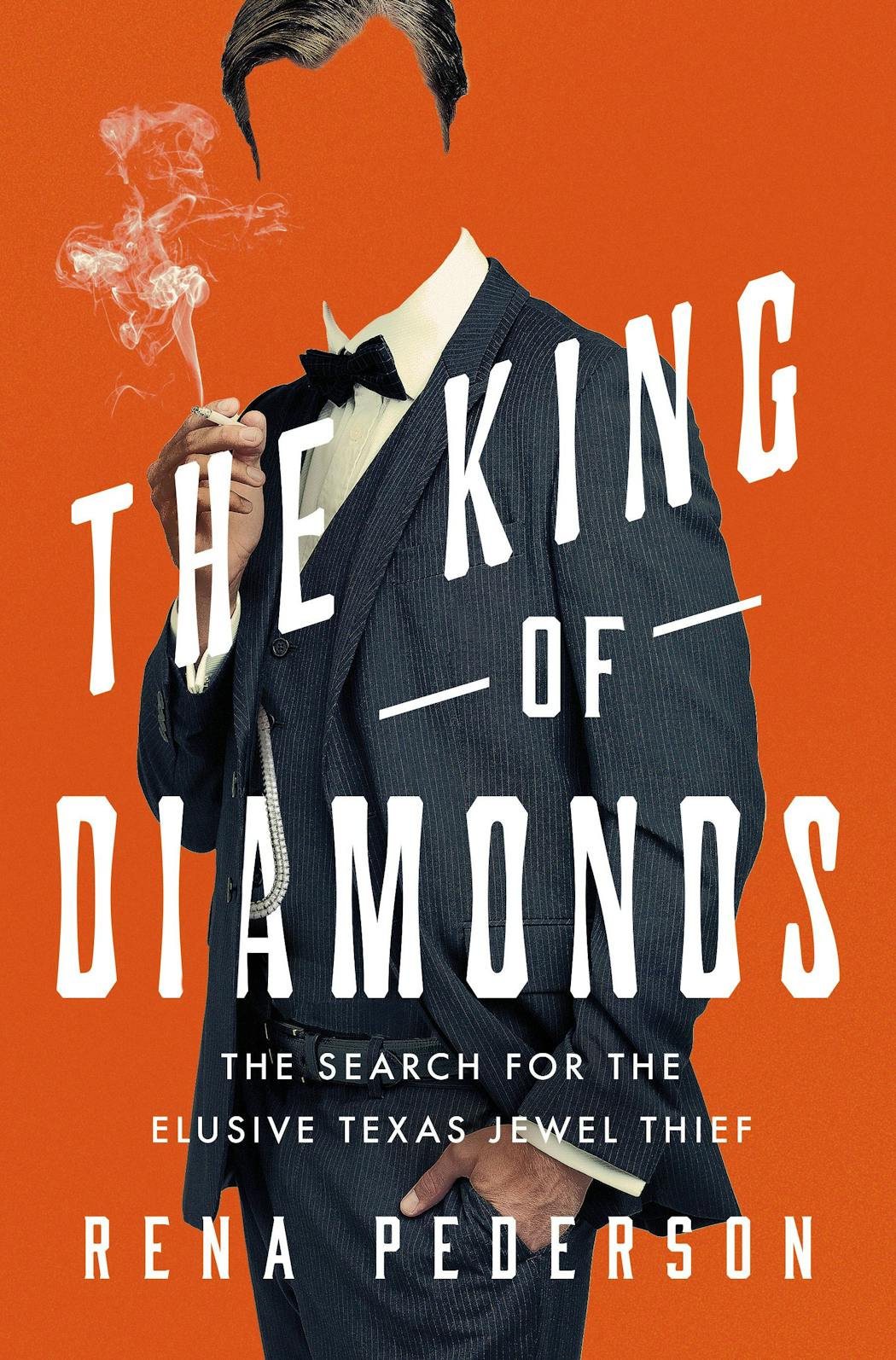

The King of Diamonds: The Search for the Elusive Texas Jewel Thief

By: Rena Pederson.

Publisher: Pegasus Books. 416 pages. $28.95.

The 5 best things our food writers ate this week

A Minnesota field guide to snow shovels: Which one's best?

Summer Camp Guide: Find your best ones here

Lowertown St. Paul losing another restaurant as Dark Horse announces closing