Dan Moulton has raised chinchillas, those cute little Andean furballs, in southern Minnesota for more than 50 years.

Moulton is licensed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and sells the chinchillas as pets, breeding stock and research animals. He used to sell them for pelts, but no longer.

The USDA license means he has regular visits from inspectors with the department's Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS). The inspectors are supposed to ensure the Moulton Chinchilla Ranch is a healthy and safe place for the big-eared rodents.

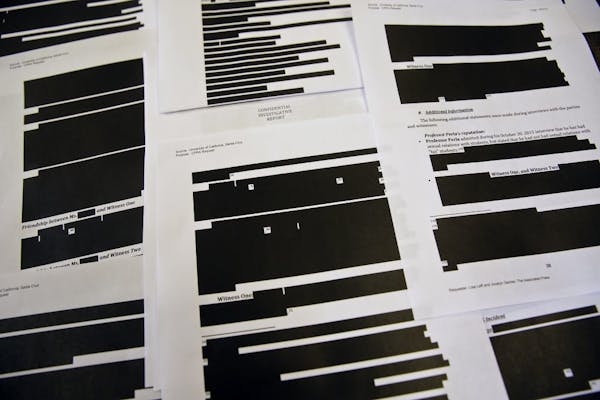

The inspectors visited twice in 2017 and both times found sick or injured chinchillas in need of veterinary care. But the public would have to do some digging to know that. The inspection reports, posted online, have the name and the address of the facility blacked out.

The public used to be able to find that information online. But early this year, the agency stopped publishing reports on inspections and enforcement of breeders, zoos, stables and other facilities licensed under the Animal Welfare Act and Horse Protection Act.

Some of those records reappeared on the USDA website in August, but the names of individuals were no longer available. There aren't many chinchilla dealers in Rochester, Minn., so that was the only way I could find Moulton.

Moulton said from his office last week (he's also a lawyer) that he is happy about the change. He had nothing nice to say about USDA inspectors, whom he said exaggerated problems found during inspections: "Those two characters are going overboard." He has the same contempt for animal welfare groups who use the records to target animal operations. "Do you know how many nuts are out there?" he said.

He rattled off examples of animal welfare activists who have broken into farms and released thousands of minks into the wild. No one has tried to free his chinchillas, but he did get an unwelcome call once from an animal rights group.

Those kinds of incidents, and a lawsuit from Tennessee walking horse enthusiasts, persuaded the USDA to stop posting new enforcement actions on its website in the summer of 2016, and then to remove the records entirely in February. Those actions prompted lawsuits from animal rights groups, who accuse the USDA of trying to hide its spotty record on animal welfare.

"It seems to be a move to protect industry and also keep the public in the dark about the practices of an agency that has been scrutinized by their own inspector general," said Delcianna Winders, a vice president of the PETA Foundation who's suing USDA.

When asked why the USDA removed this data, agency spokesman Andre Bell said, "We were trying to be responsive to our stakeholders' informational needs."

This is where the agency ended up. It posts inspection reports, sometimes of serious violations, with no indication of who's responsible. Enforcement actions are now available only by requesting them via the Freedom of Information Act.

After I made an FOIA request in June, the agency took nearly six months to follow through. I got two enforcement actions, each of them two pages long. One cited the Oxbow Park & Zollman Zoo in Olmsted County for problems with an animal structure. The other cited an unnamed licensee for an unspecified veterinary care problem.

Moulton doesn't see any need for the public to know who's getting cited. If there's truly a bad actor, the USDA can shut it down, he said.

Maybe so. But if it's public when the feds sanction dangerous truck drivers, pirate radio operators and phony organic farmers, why should we protect the privacy of people who hurt animals?

Contact James Eli Shiffer at james.shiffer@startribune.com or 612-673-4116.

E-mails, public records reveal what happened before Third Precinct was abandoned

64 years later, neighbor of mystery girl in haunting photos introduces himself

Discarded photos reveal the haunting story of a Minnesota girl