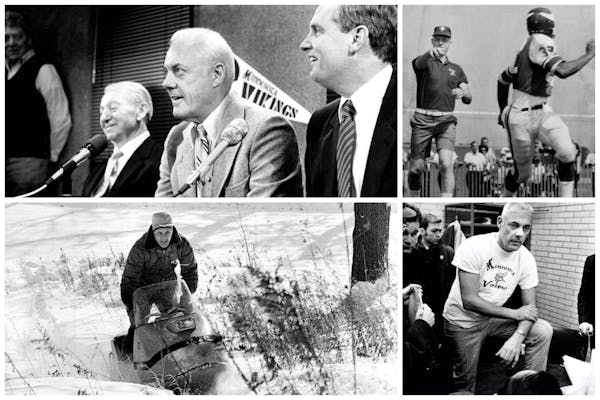

Whether Bud Grant was a football coach who happened to hunt and fish, or was a hunter and fisherman who happened to coach football, was difficult at times to tell.

Retired Minnesota state Sen. Bob Lessard first met Bud when Lessard, of International Falls, visited the Vikings' Bloomington offices in 1967, shortly after Bud was named the team's coach.

"He didn't know me. I just went to the Vikings' office and said I wanted to talk to Bud Grant," Lessard, now 91, said. "I had gone there the year before to try to talk to coach [Norm] Van Brocklin. I was managing Great Bear Lodge in Canada's Northwest Territories at the time, and my idea was to get Van Brocklin to the lodge and get some publicity out of it.

"Van Brocklin wouldn't see me. But when I went back to discuss the same idea with Grant, I got ushered right into his office. We talked for a half-hour or more.

"But that wasn't the unusual part. The unusual part occurred when I was leaving the Vikings' offices and I was about halfway to my car. I turned around and a secretary was running after me. She said: 'Excuse me, sir, but you talked to Coach Grant for longer than anyone. He's been here a while and never talks to us. We were wondering, what's he like?'

"Well, he likes to fish, I'll tell you that!" Lessard said.

Lessard, who became fast friends with Grant and remained so until Grant died March 11, recalled that after a Vikings playoff victory some years ago, Grant invited Lessard to the team's locker room.

"Bud didn't do that with many people, so I felt pretty special," Lessard said. "As I entered the locker room, Bud took me straight away to his office next to the locker room and said, 'Stay here. I have rules about who can be in the locker room. Just stay here until I get back.' "

Not long afterward, Fran Tarkenton came to the office and invited Lessard to come into the locker room to meet the players.

"I can't," Bob said. "Bud said to stay here."

"Forget that," Tarkenton said. "I'll talk to Bud. Come with me. He won't care."

So Lessard entered the locker room with Tarkenton and was shaking players' hands when Bud started yelling.

"Bob, I told you to stay in the office! You can't be in here with these players! Now get back to the office!"

Six months passed before Bud fessed up while hunting with Lessard that the whole thing was a setup between Bud and Tarkenton to lure Lessard out of the office so Bud could have his fun with him.

"It was 1991 and we were opening our first store in Sidney, Neb., and we had invited Bud to be there along with Chuck Yeager [the test pilot and flying legend]. I took them dove hunting one day, along with my young son, who, as kids will do, was taking some long shots, blasting away. Yeager dressed my son down for his shooting, and yelled at him. Bud never forgot that, and never forgave Yeager for it. It just wasn't something Bud would ever do."

— Dennis Highby, retired Cabela's CEO

Bud hadn't been in the Twin Cities long when he met Norb Berg at the now-defunct Decathlon Club in Bloomington.

"Introducing myself," Berg said, "I told Bud I had read in the paper the one thing he missed about coming to the Vikings from Winnipeg was a place to hunt ducks. I told him I had a lease in the Minnesota River bottoms right there in Bloomington, and if he'd like to hunt with me, he could.

"Bud said, 'How about tomorrow morning?' "

From that day forward, Berg and Grant were frequent hunting and fishing partners, and Grant often sought Berg's counsel on topics ranging from deer habitat to Grant's last Vikings contract.

"Bud didn't have an agent, and he didn't need one," said Berg, 91. "He had great instincts, and he knew how to fairly price his worth without being unreasonable.

"People often ask me, 'What's Bud Grant like?' Well, if you were on the same wavelength with him, he was very comfortable to be with. He was extremely curious and he liked people he could learn from. Also, he respected hard workers and determined people. If you came from a small town, from a family that didn't have much, you probably had a leg up with him. People think he was quiet, but he certainly wasn't quiet around his hunting and fishing friends. And he could be funny.

"The only time any of us tried to impress him was to show him occasionally that our dogs were better than his. Sometimes they were, but oftentimes they weren't. As he was with football players, he was very good with dogs."

"In 2010, Bud flew with the Vikings to New Orleans for the NFC championship. The plan if the Vikings won was to hand the trophy to Bud. But they lost, and about a half-hour afterward my phone rang. He knew how big a Vikings fan I am, and his first words to me were, 'Mark, are you over it yet?' Then he said, 'People always ask me if the four Super Bowl losses bother me. This one hurts more than any of them. We had a great team, and we probably would have won the Super Bowl.' "

— Longtime hunting friend Mark Hamilton of Minot, N.D.

I met Bud through Berg, and for the better part of four decades the three of us, with Lessard and a handful of others, hunted and fished together from Latin America to Alaska.

One of the first trips Bud and I took together was in 1985, when we drove to western North Dakota to hunt pheasants and sharptailed grouse with Bud's rancher friends, Dave and Molly TenBroek.

"When Bud first came to our place two years earlier, I didn't know anything about him, except that he was the Vikings coach," Dave TenBroek said.

The TenBroeks' three boys, Trampas, Jeremy and Denver, were in grade school at the time, and whenever they weren't doing chores they shot basketballs at a netless hoop beneath a yard light.

Bud always brought the boys a new NFL football, and after we finished hunting, we'd toss it back and forth on the ranch's dirt driveway.

The boys didn't cut Bud any slack when he missed a throw.

"That was a sucky pass!" Denver was famous for saying when Bud airmailed one by him on a slant pattern.

"Trust me,'' said Bud, a former NFL receiver, "it's never the quarterback's fault."

The ranch was so close to the South Dakota line that the boys attended school in McIntosh, S.D., where, later, during the first of four of the school's consecutive state high school basketball tournament appearances, Trampas (a senior), Jeremy (sophomore) and Denver (freshman) started for the McIntosh Tigers. Denver, in fact, would go on to be North Dakota State's all-time leading scorer and play in Europe and Australia, which perhaps explains why my H-O-R-S-E matches with him on subsequent trips to the ranch became evermore challenging.

Over the course of a few days, Bud and I shot some birds. Then we headed back to the Twin Cities through South Dakota on Hwy. 12. En route, I had an hourlong radio show to do, and I needed to find someplace quiet where Bud and I could connect to a Twin Cities station by phone.

"Pull in here," I said to Bud, pointing toward a ramshackle motel in a small town east of Aberdeen.

Inside, I asked the owner if I could borrow a motel room for an hour to do the show.

"Son," the man said, "I'm in the business of renting rooms, not loaning them."

Short of cash, I tried another tack.

Motioning to Bud, who was still in the car, to roll down his window and wave, which he did, I said, "That's Bud Grant and he's going to be on the show with me!"

Craning his neck, the man said, "I'll be damned."

Then he said: "Room No. 1, around the corner. It's open."

"Bud often supported fish and wildlife conservation, as he did to help get Pheasants Forever off the ground in the 1980s. At the Duck Rally in 2006 on the Capitol Mall — this was when the Legislature was still debating whether to build a new Vikings stadium — Bud looked out over the 6,000 people who attended and said that passing the Legacy Amendment to dedicate a portion of the state sales tax to conservation was more important than any stadium the state could ever build. He couldn't make his priorities any clearer than that."

— Garry Leaf, MN-FISH board member

Under Bud, the Vikings came to training camp later in July than any other NFL team. To minimize their time in Mankato, where the team's summer drills were held, he expected the players to arrive in shape, and as importantly he wanted to reserve most of July for exploration of the Canadian north with his late friend, Buzz Kaplan of Owatonna.

Kaplan ran Owatonna Tool Co., a longtime family business. A private pilot with thousands of hours in a floatplane and a passion for hunting and fishing, Kaplan every July would fly Bud in a Cessna 185 on amphibious floats (later, a similarly equipped Cessna Caravan) on trips that pushed the ice line north.

Sometimes Kaplan cached 55-gallon barrels of fuel in the hinterlands to facilitate their adventures, and some years, instead of the Cessnas, he flew his small helicopter.

"One time in the helicopter Buzz and I landed on God's River in Manitoba to fish for brook trout when a storm came in," Bud told me years ago. "We sat there for a couple of days playing gin rummy. Finally, to leave we had to push off from shore to get away from nearby trees. My job as we floated downriver was to start a small outboard motor attached to the helicopter's frame so the helicopter didn't rotate as Buzz started the overhead rotor.

"But the outboard wouldn't start and the helicopter started spinning on its floats as Buzz started the rotor. Finally, just before we were going to hit a tree, I got the outboard started and we took off. Then I had to crawl inside the helicopter. It was exciting."

"In the '60s and '70s, during the Vikings' heyday, [my late wife] Loral and I and Bud and a bunch of the Vikings — Wally Hilgenberg, Roy Winston, Lonnie Warwick and others — would go to Iowa on Tuesdays, the team's day off, to hunt pheasants. I'll always remember, at day's end, when we divided up the roosters, the players would catch Bud squeezing the birds to see which ones were biggest. Those were the ones he wanted. Well, they weren't afraid of the coach then. 'Get your hands off the birds!' they'd say. 'We'll divide those up!' "

— Chuck Delaney, owner, Game Fair

Not long ago I picked up Berg at his St. Paul apartment and Lessard at his Maplewood apartment.

"Let's go to Bud's cabin," I said.

In various combinations, with a handful of others, the three of us had hunted, fished or generally hung around with Bud for the better part of a half-century. Now those times were coming to a close.

About noon that day, Bud and his partner, Pat Smith, greeted us in the same northwest Wisconsin lakeside cabin where Bud has sought respite through all of his life phases, from his long-running marriage to his "first Pat," who died in 2009, and the raising of their six children, to the exponential growth of their family tree, with grandkids and great-grandkids aplenty.

The four of us talked about old times and about good times. Then we ate lunch.

Afterward, as we walked outside to sit alongside the lake, its blue water shimmered beneath a warm sun.

Memories were what we had in common then, and less so the future.

It had been a good day, and our last time together.

Anderson: In early June, Minnesota fish are begging to be caught. Won't you help?

Anderson: Tails wagging, DNR officers' dogs find lost people and missing evidence

Anderson: Punish poachers more

Anderson: The Chainsaw Sisters Saloon is gone, but the Echo Trail is still a pathway to possibilities