As many times as he had driven on the Gunflint Trail adjacent to the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness, Lee Frelich had never seen telephone poles burning and couldn't imagine that outfitters' canoe racks could be reduced to ashes and Kevlar watercraft vaporized by intense heat.

This was in 2007, and Frelich had paddled into the BWCA only three days earlier, with no hint of fire anywhere.

The irony was that Frelich, a University of Minnesota professor and a renowned forest-fire researcher, was caught off guard by the quickly advancing Ham Lake fire.

Yet he could see it coming — if not that blaze, a similar or even larger fire this summer, or in future summers, due in part to the increasing frequency of "flash droughts'' similar to the one that gripped Minnesota in May and most of June.

June 2023 will go down as the driest on record in the Twin Cities, and the third hottest. The Boundary Waters were parched, too: the period June 1-19 was the driest ever in northeast Minnesota, contributing to explosive fire conditions that were doused by timely rains — this time.

"The climate is changing and the world's boreal forests, which the BWCA forest is, are one of the most flammable forest types in the world,'' Frelich said. "It's no accident that millions of acres of these forests are burning across Canada and have burned in recent years in northern Scandinavia and Russia. The area burned by these fires has been going up, but the number of fires has not. The only way that can happen is if each fire is getting bigger because of warmer, drier fuels.''

Greg and Julie Welch were caught in a BWCA fire, too.

On the second day of their canoe trip in 2011, they were surprised to see forest-fire smoke clouding the near distance.

They were told nothing about imminent fire danger when they picked up their BWCA permit from the U.S. Forest Service in Tofte — only that a small fire was burning in a distant location in the BWCA.

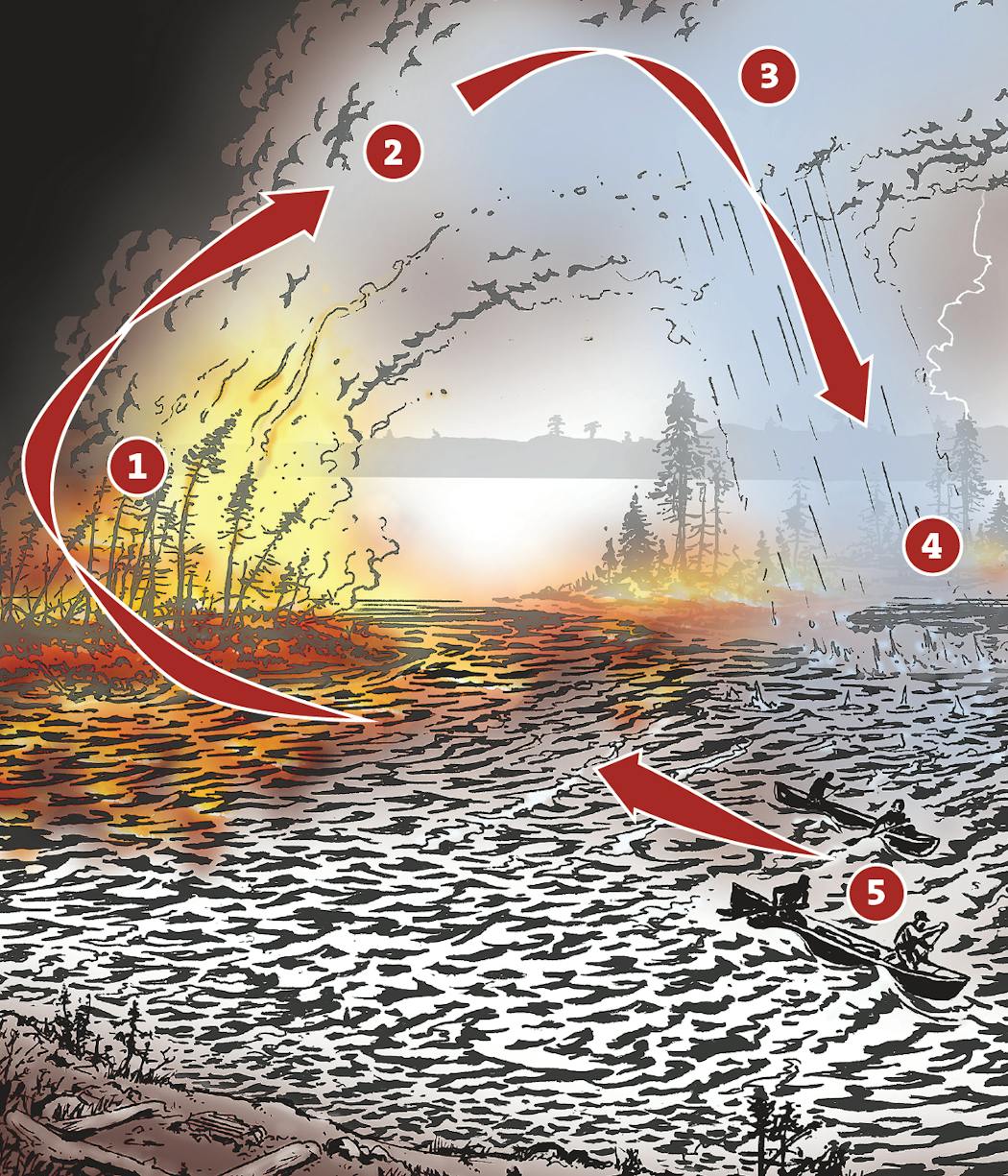

But soon after spotting the smoke, they were rained on by burning embers, Julie's kayak was flipped by 50-mph gusts, and the two of them were splashing in Kawasachong Lake, clinging to Greg's kayak and fighting off hypothermia while the world around them went up in flames.

"The sound was like several freight trains coming at once,'' Greg Welch said. "I was worried about losing Julie when she started shaking, so I tied her wrists to my kayak.''

Breathing through Greg's water-soaked fleece to filter the acrid smoke, the Michigan couple struggled in the wave-tossed lake. When Julie began to shiver uncontrollably, they crawled onto a rock outcropping.

As they did, the firestorm fueled its own cataclysmic weather. A massive smoke plume billowed 38,000 feet into the atmosphere, chased by orange and yellow flames, while lightning crackled and thunder boomed.

First, rain drenched the two paddlers, then hail pelted them.

This was the Pagami Creek inferno, which the Forest Service had watched smolder for days without fighting it. Then ideal fire conditions coalesced — hot weather with low relative humidity and high winds — and within days, Minnesota's largest naturally ignited fire in more than a century had burned 92,000 acres.

Lessons were learned from that fire, said Ely Forest Service District Ranger Aaron Kania, a relatively recent transplant to Minnesota. Just like lessons were learned from the Cavity Lake BWCA fire in 2006, which torched more than 23 square miles in three days, and the Greenwood fire in 2021, which incinerated 27,000 acres of semi-wild lands near the BWCA over about a month.

Usually, BWCA fires are extinguished fairly quickly, Kania emphasized, and without loss of life or property.

Last month's Spice Lake fire off the Gunflint Trail, which burned only 22 acres, is an example of how the Forest Service, the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources and other agencies, working cooperatively, can jump on fires soon after they're spotted.

But under the right conditions — conditions that are more likely these days, Frelich and other experts say, because Minnesota is experiencing earlier springs and later falls, which produce drier forests — some Boundary Waters fires will do unpredictable, and unimaginable, things.

Acknowledging as much, Kania said, "They're called wildfires for a reason.''

Lane Johnson is thinking about BWCA fires in a new way that is actually an old way.

So is Chuck Dayton.

Maybe, Johnson said, instead of managing the BWCA as a federally protected wilderness "where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain'' — language that celebrated the BWCA's inclusion in the U.S. wilderness system in 1964 — the presence of people in the region for some 9,000 years before 1964 should be acknowledged.

That's when Indigenous people first migrated into what is now the BWCA, following a host of wildlife that inhabited the region after the retreat of the last glaciers.

"The archeological record shows there was a continuity of human use throughout the border region dating back that far,'' said Johnson, a research forester at the University of Minnesota's Cloquet Forestry Center.

Those long-ago people living in what is now the BWCA not only endured fire, Johnson said, they regularly set strategically placed fires. Often these were on south-facing, pine-cluttered points of land they inhabited — the same points that BWCA paddlers seek out today for their Northwoods beauty and for the breezy, often bug-free campsites they provide.

Periodic burning not only removed combustible brush and other understory that otherwise would ensure calamity during a firestorm, it provided a steady supply of blueberries and raspberries while encouraging game — perhaps caribou, moose, deer and hares — to inhabit the burned-over area.

Importantly, this practice also preserved the pines, some of which even today in the BWCA date to the 1700s. Without the fires, which pines need periodically to blacken their lower trunks, the towering trees would have been lost to fire long ago.

All of which changed beginning in the mid- to late 1800s and early 1900s, when Minnesota gained statehood, treaties were signed with Native Americans, reservations were established and loggers moved into the boundary waters' periphery to fell pines.

Serendipitously, pines in the region's interior, with its rugged, inaccessible terrain, escaped the loggers' axes.

About the same time, the Forest Service's first director, Gifford Pinchot, responding to the "Big Blowup'' of forest fires in the northwest U.S. in 1910, began a national policy of extinguishing forest fires as quickly as possible. The intent was to preserve trees for the timber industry. But the policy also contributed to a buildup of forest fuels, setting the stage for massive forest fires in years to come, including as recently as 2022 when nearly 8,000 fires raged in California.

Fast forward to 1978, when Congress OK'd the most recent BWCA law, which expanded the wilderness to 1.1. million acres, reduced motor travel and outlawed logging.

Dayton, now 84, whose hand has touched virtually every piece of state environmental legislation dating to the early 1970s, helped write the BWCA law.

Now he's not so sure he and others got everything right.

"I think fire management in the BWCA needs to be re-examined,'' Dayton said, "particularly in light of climate change.''

Otherwise, when large fires such as Cavity Lake, Pagami Creek and Greenwood occur, as they inevitably will, Dayton said, chances increase that the BWCA's red and white pines will be lost, along with its signature black spruce, jack pine and paper birch, to be replaced by a succession of lesser trees that lack the aesthetic value of pines and are less climate resilient.

Johnson agrees.

"Keeping the pines in the BWCA is critical to the ecological integrity of the whole system,'' he said. "Eagles and ospreys, for example, don't often nest in trees other than pines. Additionally, pines are more climate resilient than other trees, and with their deep roots they sequester carbon, mitigating the warming effects of climate change.''

Kania, the Forest Service district ranger in Ely, said that interpreting the 1964 and 1978 BWCA laws to allow prescriptive burning of the kind Johnson, Frelich, Dayton and others are describing would require high-level talks among wilderness advocates, tribal leaders, the Forest Service and perhaps others.

"We currently have a Forest Service policy that allows us to do prescribed burns in the BWCA to reduce hazardous fuel loads, such as those from the big 1999 blowdown,'' Kania said. "The types of low-intensity, high-frequency fires that Indigenous people used historically are being employed elsewhere in the nation, but haven't been talked about for the BWCA, to my knowledge.''

That said, earlier this year the Forest Service signed an agreement with the Bois Forte Band of Chippewa, the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa and the Grand Portage Band of Lake Superior Chippewa calling for "co-stewardship and protection of the Bands' treaty-reserved rights under the 1854 Treaty within the Superior National Forest,'' which includes the BWCA.

Already, low-intensity, high-frequency fires are being deployed on the Fond du Lac Reservation under the guidance of band staffer Damon Panek. Some of the fires produce blueberries, while others yield crops for traditional medicines or other purposes.

Dayton believes enough legal wiggle room exists in the 1964 BWCA Act, and in Forest Service regulations, to allow low-intensity, high-frequency prescribed fires.

In addition to prolonging the ecological integrity of the BWCA in a time of climate change, he said, the change would acknowledge for the first time that the region is a product of many influences, including people and fires set by people.

"Forest Service provisions that prohibit the use of prescribed fire for wildlife or vegetation enhancement should be amended in light of recent studies showing the use of aboriginal burning,'' Dayton said. "This would be consistent with the history of the wilderness before the arrival of Europeans, and is necessary to preserve the BWCA wilderness as we now know it.''