Story by Adam Belz • Photography by Jim Gehrz • Graphics by Michael Grant and Jeff Hargarten • Star TribuneDec. 29, 2016 — 12:00AM

Sylvia Hilgeman grew up no-frills on a farm in Red Lake County in northwest Minnesota, where flat fields are broken by steel grain bins, stands of aspen and abandoned farmhouses.

Her dad cultivated rented land and her mom raised cattle and milked cows at a neighboring farm to help pay the bills. They raised their children in a double-wide mobile home across a gravel driveway from her great-uncle's homestead.

"My parents, they worked harder than anyone I've ever met," Hilgeman said.

The work paid off for their children. Sylvia went to college, got a job in accounting and later joined the FBI. Today, she investigates white collar crime in New York City.

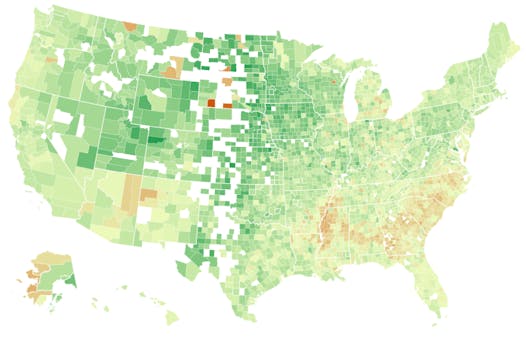

Compared with cities and suburbs, it is much easier to move up into the middle class from rural Minnesota, North Dakota, South Dakota, Iowa and Nebraska. Well-off and hard-up kids go to school together in small towns. They come of age in tight social networks that run through extended family, neighbors, church, school and fields. They feel pressure to work hard and succeed.

Among these rural communities, Red Lake County stands out. Children born there into a family in the middle of the bottom half of the socioeconomic ladder have, on average, landed better off as an adult than six in 10 Americans in their age group, according to an analysis by economists at Harvard and the University of California, Berkeley.

The numbers are more similar to Scandinavian countries, which score particularly high in this regard, than to urbanized areas of the United States.

"The rural areas seem to produce really good outcomes for kids from low-income families," said Raj Chetty, an economist now at Stanford who led the research. "Minnesota actually looks very much like Denmark."

While the recent presidential election spotlighted frustrations among the rural middle class about wage stagnation and dimming economic opportunities, children from low and middle-income families in rural areas have been more likely to reach the middle class than their urban counterparts.

The catch is that many of these kids achieved prosperity only by moving out of farm country. The small towns of the Midwest, where opportunity is highest, are less and less the places where most people live, or where poor children grow up.

Only 10 percent of Minnesota's last generation of children grew up in high-opportunity counties, and that share is gradually shrinking.

'WORKED HARDER': Sylvia Hilgeman left home to work in New York, but she visits at least once a year. Hilgeman, whose photo with FBI Director Robert Mueller is on display at home, said there were lean times growing up but the family has prospered. "My parents, they worked harder than anyone," she said."You need a certain kind of critical level of human beings to make a community work, to have enough people in your church and your school, and have all the township officers and all those different things," said Sylvia's dad, Greg Hilgeman. "Grain farming does not employ enough people."

Prepared to succeed

Of the best 100 counties in the United States in which to grow up poor, 77 are in Iowa, Nebraska, Minnesota, North Dakota and South Dakota, according to the data Chetty and his colleagues published. Almost all of those are in farm country.

In Minnesota, the counties with the highest opportunity for low-income children are along the west border and in the south-central part of the state. Children who grow up in small towns grow up in places with lower starting incomes, and so if they go to college and get a good job after school, they are in position to do better than their parents, said Ben Winchester, a University of Minnesota Extension rural sociologist.

They usually end up in urban centers when they grow up, because that's where well-paid jobs are.

"This out-migration of our kids is actually a really good thing. One predictor of mobility is out-migration," Winchester said. "You don't necessarily get upward mobility in the community you're raised in. You get upward mobility because your community prepared you well."

Explainer

ut upward mobility isn't just a matter of moving where the jobs are.

Dano and Kelsey Stephens grew up 12 miles apart — he in Red Lake Falls and she in Plummer. They both went to Bemidji State University, got married, and moved to Texas after college so she could take a job as a 3-D designer for a firm that makes huge banners and exhibits for trade shows.

The couple moved home in 2010 so their children — they now have a girl and a boy — could be closer to their grandparents. Kelsey works remotely for the same firm in Dallas. Dano is a financial adviser for Thrivent. Last fall their friends and family helped them pour a concrete slab for a new house they're building.

They feel like their family is moving up.

Dano Stephens' dad was an ironworker right out of high school. As his children got older he shifted into a job that didn't pay as well but also didn't require as much moving — locating underground lines for local utilities. Stephens' mom went back to college to train to be a lab technician.

"When I was a kid we were pretty strapped, I remember," Stephens said. "Not having a lot of extra income and not having the nicest vehicles in the world. Then we all went off to college, me and my sisters, and kind of turned things around and got on a better footing."

Maybe it was the drive to move on to bigger things, and maybe it was just the community's expectations, but most people in Dano Stephens' class at the high school in Red Lake Falls graduated and went on to pursue higher education.

"Almost everybody went to college on some level," he said. "Parents put an emphasis on it, I guess."

he rural recipe

Sylvia Hilgeman, 31

Location: New York City

Job: Special agent with the FBI

Family: Single

Housing: Rents an apartment in Brooklyn

Hometown: Oklee, Minn.

On growing up in Red Lake County:

The rural Midwest has had an unusually good run in the past 20 years. Not only did high corn and soybean prices make farmers rich after the lean years of the early 1990s, but the North Dakota oil boom had some carry-over effect to other states, including Minnesota.

But the improvement in families' fortunes is not just a result of an improved economy.

"There's something more persistent … that goes back to the 90s and that's showing up before kids actually start working," said Chetty, the economist.

Low-income people who grew up in towns like Oklee or Morris or Pipestone were less likely to grow up in single-parent households or have children as teenagers than the average poor American. Rural Minnesota has better schools than the U.S. average, and less income inequality. It also gets high marks for what the researchers call "social capital," a combination of high civic participation, voter turnout and religious adherence, and low violent crime rates.

The rural advantage is not simply a function of having a mostly white population either, Chetty said. While it's true that places with higher black populations offer poor children less opportunity, that lack of opportunity is color blind, affecting black and white children in those neighborhoods. White children do worse in poor, segregated places. Children of color do better in integrated ones.

The key factor for all children is to grow up in a place where different economic classes live together, he said. In cities, the rich and poor live largely separate lives, and in the country everyone grows up together.

"All classes are forced to interact in a small town," said Winchester, the U sociologist. "Rugged individualism got our population here, but community keeps us here."

ylvia Hilgeman's dad, Greg, grew up in Minneapolis. But he liked visiting his uncle, Milan Rustan, and preferred working on the farm over life in the city. After high school he went to work for his uncle. His future wife, Gayle, grew up on a nearby farm, the oldest of seven and a veteran of 5 a.m. milking on her family's dairy farm by the time she was in grade school.

The couple had three children — Frances, Sylvia and Scott. Even though there was little money around in the early 1990s, Sylvia was raised in a community where the old cliché was true: Everyone knew everyone and helped raise everyone else's kids. She had some of the same elementary school teachers as her mother.

"Quite often, your fourth grade teacher is your baseball coach and your Sunday school teacher and your parents' friend," said Brad Kennett, the principal of Red Lake Falls High School and a native of Fort Frances, Ontario.

Sylvia Hilgeman was a standout point guard at tiny Oklee High School, which has since merged with the school in Plummer, and a straight-A student. She won a scholarship to study accounting at Jamestown University in North Dakota, the school where her older sister got a degree in nursing. The Red Lake Electrical Cooperative kicked in $300.

"It was just sort of a given that you would go to college, like, a given for everyone, not just me," Hilgeman said. "That was just what people did. And I'm not sure that's the case everywhere."

After college, she spent five years working for the consulting giant Deloitte in Minneapolis before she joined the FBI to investigate bank fraud from New York City. She can't talk much about her work, but she made the jump because she wanted to do something more meaningful, she said.

She comes home to visit at least once a year, and the family has prospered. Her parents built a new house a couple of years ago. Hilgeman sits in the tractor cab with her brother while he discs a soybean field, drinks coffee in the kitchen with her mom, plays with her nieces and nephews from Thief River Falls and rides along as her dad races the red border collie in the Gator.

"I don't remember a time," she said, "that I didn't believe I could do anything that I wanted to."

adam.belz@startribune.com 612-673-4405Finding opportunity

The ability to rise to another income level varies by region, but the Upper Midwest stands out as an exceptionally good place to raise a family.