Brad Edgerton takes particular pride in one simple gesture amid his great-great-grandfather's many accomplishments: After commanding a regiment of Black soldiers during the Civil War, Alonzo Edgerton invited a family born into slavery to join him when he returned home to Minnesota.

"To me, that's the unique part of his story," said Brad Edgerton, 66, a retired orthopedic surgeon from Duluth. "Everyone knows the North was sympathetic to Black people, but Alonzo walked the walk and followed up the talk with philanthropy for a family he loved."

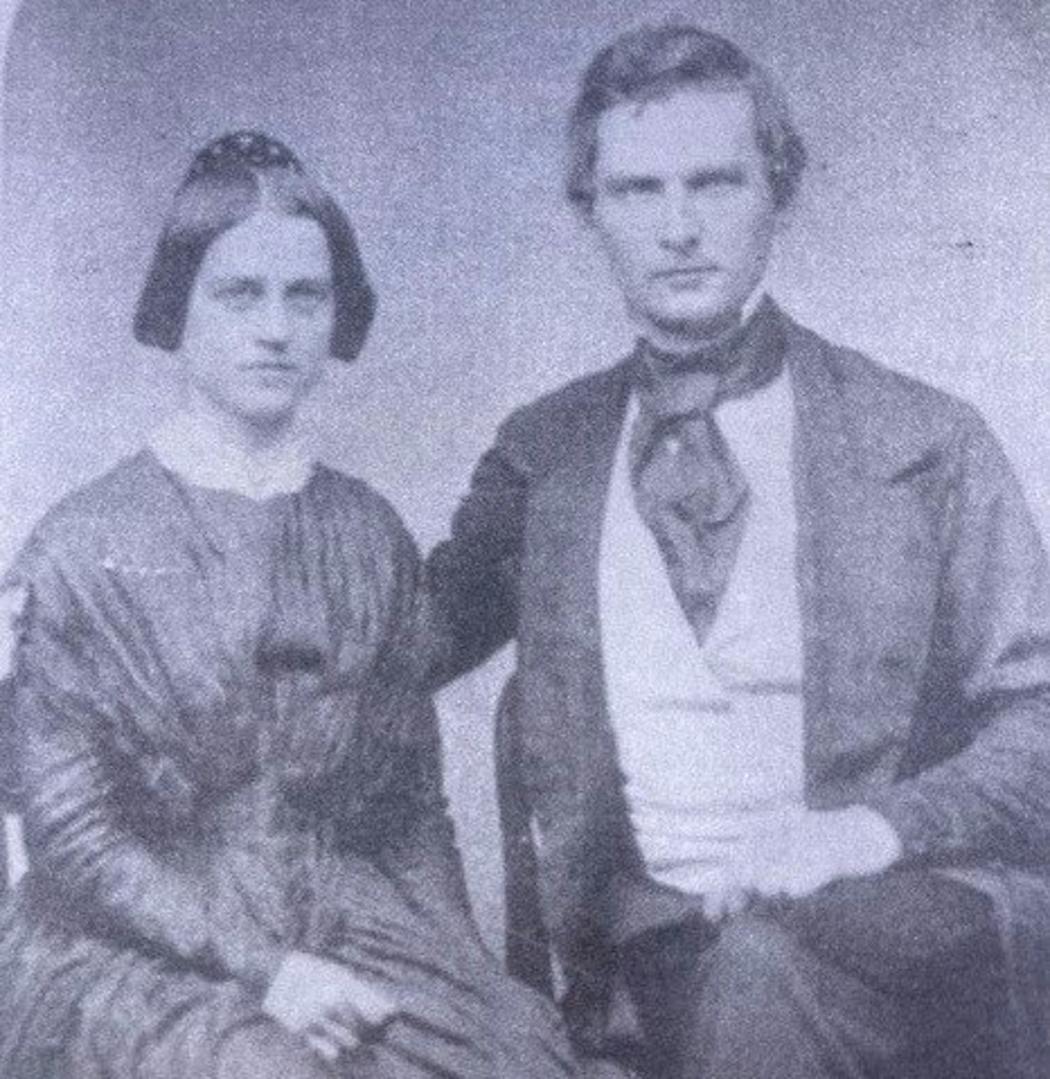

Born in New York in 1827, Alonzo Edgerton moved to Mantorville with his wife Sarah in 1855, three years before Minnesota statehood. He'd go on to become one of the young state's "very able lawyers … an influential Republican politician, and a leading man at all times," according to an 1877 biographical sketch.

Alonzo became the state's first railroad commissioner in 1872, served in the state Senate and did a stint in the U.S. Senate in 1881. He was a University of Minnesota regent, served as chief justice of the Dakota Territory Supreme Court in Yankton, and went on to become a federal judge in South Dakota. The southwestern Minnesota town of Edgerton, famous for its state basketball championship upset in 1960, was named for him.

When Brad was a resident at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester in the late 1980s, he visited the Dodge County Historical Society in Mantorville and asked if they had any information about Alonzo Edgerton. The docent pointed to a large portrait of the bearded pioneer hanging on the wall.

"It was kind of cool," Brad said. "He bore a striking resemblance to my father."

Alonzo's actions during the Civil War, and immediately afterward, eclipse all his impressive honors and titles, Brad said.

When the Civil War erupted, Alonzo Edgerton rode an old white horse across Dodge County recruiting soldiers for Company B of the 10th Minnesota Infantry Regiment. He quickly rose through the ranks from private to colonel and brevet brigadier general — and would be known as "the General" until he died at 69 in 1896 of kidney failure.

After battles in Missouri and Louisiana, Edgerton took command in 1864 of the 67th U.S. Colored Infantry, which included 316 Black soldiers from Missouri who'd been enslaved.

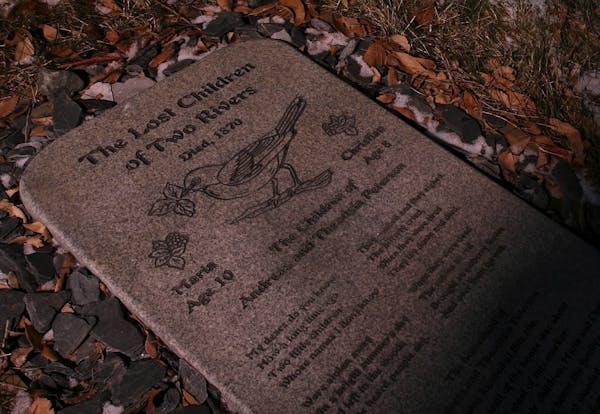

That's where he first crossed paths with Simon Boggs, who was born into slavery in Missouri around 1825. Boggs, who had been separated from his first wife and children during slavery, met Flora at the end of the war and married her.

"The sympathy between them that naturally grew out of their common experiences as slaves, ripened into a warmer attachment, until they joined their right hands in a marital pledge that proved more binding and inviolable than many," according to a article in the Mantorville Express that ran after Flora died.

Simon, Flora and her two sons from a previous marriage, Henry and Lewis, accompanied Alonzo when he returned to Mantorville to practice law in 1867. Simon, a laborer according to census records, and Flora remained there for more than 30 years.

"They were quite curiosities at that time, but they certainly did well, for out of slavery, they became useful members of the community," wrote Margaret Edgerton Holman, one of the General's 10 children, in a family memoir in 1919.

Another of Alonzo Edgerton's daughters recalled her childhood friendship with Henry and Lewis Boggs as kids in Mantorville.

"People weren't like the way some of them are now. We never thought about the Boggs family as being different," Sarah Emma Edgerton told Minneapolis Tribune writer Barbara Flanagan in 1964 when the General's eldest daughter turned 100.

Simon Boggs eventually was reunited with a daughter he'd lost track of during slavery. She came up from St. Louis and spent a few weeks with her father, according to the Mantorville newspaper.

Flora Boggs was ironing clothes in her house on the west side of Mantorville when she suffered a sudden heart attack and died in 1903. By then, her son Henry was living in St. Paul and his brother Lewis had moved to Blooming Prairie.

"The deceased will always be kindly remembered by those who have known her as industrious and honest, and of a sunny disposition and a kindly heart," the Mantorville Express published.

Simon Boggs died two years later in 1905 when his rheumatism led to heart failure. His name is etched in the African American Civil War Memorial in Washington, D.C. He and Flora are buried in Mantorville's Evergreen Cemetery, as are Alonzo and Sarah Edgerton.

"My dad told me Alonzo was a benevolent guy who took this family freed from slavery and provided financial support to set them up in a home not far from his in Mantorville," said Brad Edgerton with pride.

Curt Brown's tales about Minnesota's history appear every other Sunday. Readers can send him ideas and suggestions at mnhistory@startribune.com. His latest book looks at 1918 Minnesota, when flu, war and fires converged: strib.mn/MN1918.

Minnesota History: Ad man turned Paul Bunyan into a folklore icon

Minnesota History: James Griffin used persistence to blaze a trail for St. Paul's Black police officers

Minnesota History: For Granite Falls doctor who tested thousands of kids for TB, new recognition is long overdue

Minnesota History: A New Ulm baker wearing a blanket fell to friendly fire in the U.S.-Dakota War