In 1937, Minneapolis motorcycle cops escorted 12-year-old Walter Shimshock and his 13-year-old brother Bernie to the Great Northern Depot, along with the other outstanding Tribune carriers about to embark on an all-expenses-paid trip to Chicago.

Seven years later, Nazis executed Walter in Poland — pouring bullets into the 19-year-old U.S. Army Air Force rear gunner from northeast Minneapolis, fresh out of DeLaSalle High School.

Staff Sgt. Shimshock had bailed out of his burning B-17 bomber that was dropping supplies for Polish resistance fighters, who were then locked in a two-month clash with occupying German forces, now known as the Warsaw Uprising. He broke his leg parachuting down to the waiting Nazis, who interrogated and tortured him before killing him.

Bernie clung to memories of that Chicago trip with Walter, and watching the Cubs play the Dodgers, until his own death in 2005. His brother was just a kid when he entered World War II, Bernie told the Star Tribune in 2004.

"Biggest thing we ever did before he went in was a trip to Chicago in 1937 to see our first baseball game and ride on the El," Bernie said.

Now, despite dying as a teenager 80 years ago this September, Walter Shimshock will further cement the ties between sister cities nearly 4,700 miles apart — Columbia Heights and Lomianki, Poland.

A memorial to Shimshock and his nine airlift crewmates will be unveiled next month at Huset Park in Columbia Heights, a couple miles north of Walter and Bernie's childhood home in northeast Minneapolis. The Warsaw Uprising Airlift Memorial, a triangular obelisk and plaque, mirrors a similar monument that Polish leaders erected two years ago at the crash site of Shimshock's bomber outside Lomianki.

Never mind that Shimshock's B-17 was the only one of 107 Allied bombers shot down while dropping hundreds of canisters of food, ammunition and medicine on beleaguered Warsaw on Sept. 18, 1944, during a mission called Operation Frantic 7.

"One plane might seem to mean nothing in the complex scheme of a terrible war, but to us that one plane meant that they were coming — freedom was near," Lomianki's village priest said at the dedication of a granite memorial to the B-17 crew in the city's war cemetery in 1987.

When Minnesota Gov. Tim Pawlenty paid his respects at that memorial in 2004, Lomianki Mayor Lucjan Sokolowski said: "We will never forget the courage of these magnificent fallen American airmen. They gave their lives out of a sense of duty. We will never forget their sacrifice."

It was Bernie, a Columbia Heights resident (who used the Polish spelling of his family name, Szymczak), who helped set up the partnership between Columbia Heights and Lomianki in 1991. Walter's death served as "the impetus for the relationship," according to Karen Karkula of Minneapolis, a longtime member of the Polish American Cultural Institute of Minnesota. The organization published a detailed account of Shimshock's crash this month.

Karkula, a former Columbia Heights resident, helped secure a grant that led to the English translation of a Polish book, "Frantic 7,″ that details Shimshock's 13th and final mission.

After German anti-aircraft fire hit the bomber — named "I'll Be Seeing You," after a Bing Crosby hit — three of the 10 crew members, including Shimshock, parachuted out. At least six and possibly seven of the crew members died when the blazing plane exploded on its way down.

Shimshock is believed to have survived briefly before being questioned, tortured and executed, likely because of his Polish heritage. The other two crew members who successfully bailed were taken as prisoners.

"Frantic 7″ includes a telegram sent a week after the bomber crashed, from a Polish resistance commander who offered what is now a largely accepted account of Shimshock's fate. He said an unidentified airman with a broken leg was captured and questioned without getting medical assistance.

"He behaved like a soldier. After being tested he was shot," the underground leader reported, describing the airman as "tall and blonde, about 22 years old" and carrying "a photograph of a young girl."

Shimshock's draft card listed him as 5-10½ with brown hair, though Bernie said he was blond in a 1986 interview with the Minneapolis Star and Tribune. And Shimshock was known to carry a photo of his younger sister, JoJo.

Bernie said Walter's death was wrenching for their father — framemaker and World War I vet Frank Szymczak — and Walter's three siblings.

"But it was Mother that suffered the most," said Bernie. When Walter's remains were returned for reburial in 1949 at Fort Snelling National Cemetery, it helped her to know that Walter was "back here with us" — where he played baseball and street hockey and grumbled about the early wake-ups his paper route required.

"He got drafted in 1943, not too long after he graduated from DeLaSalle," Bernie said in 2004. "Never even had a girlfriend."

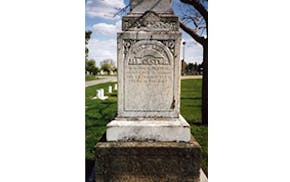

The public is invited to two ceremonies honoring Shimshock on Sept. 21: a 9 a.m. wreath-laying at his grave at Fort Snelling National Cemetery, and the unveiling of the crew memorial at 12:45 p.m. at Huset Park in Columbia Heights.

Curt Brown's tales about Minnesota's history appear every other Sunday. Readers can send him ideas and suggestions at mnhistory@startribune.com. His latest book looks at 1918 Minnesota, when flu, war and fires converged: strib.mn/MN1918.

Minnesota History: Ad man turned Paul Bunyan into a folklore icon

Minnesota History: James Griffin used persistence to blaze a trail for St. Paul's Black police officers

Minnesota History: For Granite Falls doctor who tested thousands of kids for TB, new recognition is long overdue