It was 3 p.m. on a weekday and the newly renovated hospital in Grand Marais, Minn., should have been buzzing with activity. Normally, patients would have been waiting to see doctors and hallways would have been busy with technicians leading patients to scans and blood tests.

But on this recent day — and every day for the past seven weeks — the lobby's cushioned chairs sat vacant as the few staffers working wait for the first COVID-19 case to show up in northeastern Minnesota's Cook County.

"We have one patient right now. I think we had two earlier this week," said Kimber Wraalstad, North Shore Health's chief executive, as she walked through the hospital's quiet corridors. She missed seeing the staff care for familiar faces in her small community, she said. "It just makes me sad because this is just not what we do."

For years, many hospitals in rural America have had tighter operating margins than their urban counterparts. Financial pressures have pushed many to merge into much larger health systems that can profitably operate across rural communities. Even so, the deadly COVID-19 virus has left gaping budget holes after nonemergency procedures that generate revenue were put on hold in anticipation of a virus case surge that has yet to materialize in many small towns.

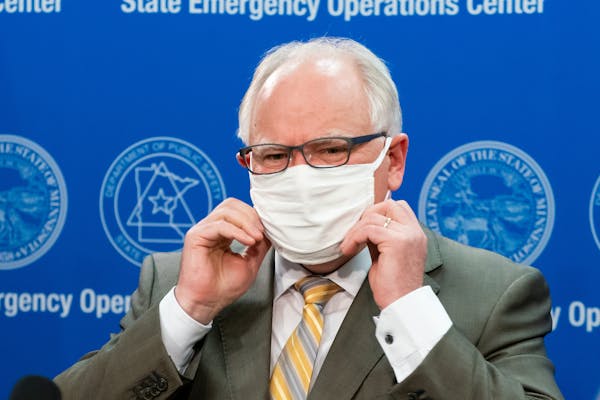

While some relief is coming after Gov. Tim Walz signed an order this week allowing some surgeries and other procedures to resume, hospitals and clinics likely won't return to business as usual any time soon — and revenue won't quickly bounce back.

"There's still great concern about the budgets," said Mark Jones, executive director of the Minnesota Rural Health Association. "How we get back to a profitable rural health care system that can continue to serve our patients is yet to be seen. Will it need to be retooled? … Will it ever go back to what we had prior to this? I don't know."

While reopening for some surgeries will begin to help financially, Jones said, there is fear among some staff and administrators of using too much personal protective equipment as well as trepidation among some patients who will continue to delay procedures and checkups.

Nationally, "many rural hospitals were already very ill. Those that survive the COVID virus will be ill when the COVID effects are no longer here," said Dave Mosley, a partner with the Washington, D.C.-based Guidehouse consulting company. Although the federal government is stepping in to help health care agencies, including saying it will cover costs of uninsured COVID patients, "the ones [hospitals] that are going to have the greatest financial issues may be the hospitals that did not see any COVID people."

'Still a tight wire'

At North Shore Health in Grand Marais, revenue dropped by $500,000 in April, the first full month of reduced services because of the pandemic.

"We've only got about a $20 million total revenue volume, so a half a million dollars a month is pretty significant," Wraalstad said of the hospital, which gets taxpayer money.

Administrators were already looking at whether some services should be trimmed and advocating for more funding from various sources, Wraalstad said, noting her hospital sits two hours from the next-closest facility in Minnesota.

Federal CARES act funding payments of just over $330,000 have helped, but "it didn't take the load off my mind, let's put it that way," she said.

Besides a license for 16 hospital beds, the North Shore Health system has an emergency department, an ambulance, a 37-bed nursing home and a home care program.

It's difficult to cut back on already minimal staffing, Wraalstad said. At certain times, just two nurses might be on duty.

"You can't tell one to go home," she said. "It's hard to do emergency care when you have less than that."

Reopening to surgeries and other procedures will help, Wraalstad said, but she hopes more COVID testing of all patients will help preserve personal protective equipment for a predicted surge of the virus.

"It's still a tight wire and we, I think in health care, still want to do the right thing for everybody," Wraalstad said. "We want to take care of the patients that have needs right now … at the same time we want to be very cautious and judicious of what we may need in the future."

Thin operating margins

In many cases, Minnesota hospitals are part of systems that offer high-priority but money-losing community services such as nursing homes, ambulances, mental health and home health. Hospital profits are used to subsidize those services, a February 2020 report from the Minnesota Hospital Association pointed out.

In 2018, Minnesota hospitals' median operating margin was just 1.7%, the report showed. And while operating margins for urban hospitals have been trending down, they were still at 2%, slightly above 1.6% for rural hospitals.

Nationally, residents living today in rural communities tend to be either very old or very young, according to Guidehouse's 2020 Rural Hospital Sustainability Index; Those communities "often have higher rates of uninsured, Medicaid, and Medicare patients, leading to more uncompensated and under-compensated care."

But Minnesota's rural hospitals have fared well compared to national trends, which show rural hospitals have been closing for years. Some rural Minnesota hospitals survive by increasing some services but cutting others.

"Minnesota's smaller and rural facilities have actually done a good job of trying to remain viable and relevant," said Dr. Rahul Koranne, president of the Minnesota Hospital Association. "Part of that has been at the expense of making some very difficult changes in their service lines."

Before the pandemic hit, an analysis of financial viability of rural hospitals in Minnesota showed that eight hospitals — 11% — were at high risk of closing unless their financial situations improved, according to Navigant, a Guidehouse company.

A gradual start

At Grand Itasca Clinic & Hospital in Grand Rapids, this year started out strong, said chief executive officer Jean MacDonell. When coronavirus became prominent, the organization lost about 40% of its total operating revenue per week. The operating room was the hardest hit, with revenue dropping about 95% at one point, MacDonell said.

This week, she said, nearly one-third of the workforce — 200 out of 650 employees — was on unemployment.

Getting some surgeries back is a "big relief," MacDonell said. "We'll start with those cases that were elective six weeks ago that have now become urgent" such as bladder tumors, breast biopsies and unstable hernias.

But hospitals will still be limited by equipment supplies and willing patients.

"It's a little early to make a projection" long-term, said Todd Christensen, Grand Itasca's director of finance. "I don't think there's any way a hospital system in the state is going to make their operating budget this year."

At St. Elizabeth's Medical Center in Wabasha, patient revenue was down about 50% in April, officials said. With 70-80% of the people it serves on Medicare or Medicaid, the system used to break even and made most of its capital improvements through community donations, President Tom Crowley said.

Administrators and staff are hoping to start performing a few surgeries beginning May 20. "We're excited to start moving forward … It'll be a gradual start," Crowley said. "It will take us some time to see how all of this plays out."

The pandemic of 2020 may change the future of health care, Crowley said.

"I think that maybe we've started to crack the door open a little bit that not every patient will have to come to the clinic in the future," he said. Provided the country builds good broadband infrastructure, "there'll be more telehealth. That might be better for the patient as well as for the cost of health care … We're getting an education through this process."

Jones, of the state rural health care association, said he is confident providers will find a way to serve people.

"I don't know if it will ever go back to just like it was, but I do know our rural providers, with their innovation and their ingenuity, they will come to a place where the rural residents are served very well," Jones said. "It's always a balance between profits and community, and in our rural communities that community really drives what we do."

Pam Louwagie • 612-673-7102

Want to share info with the Star Tribune? How to do it securely

'Safe recovery sites' would offer syringes, naloxone and more to people using drugs. The plan could be in peril.

New Minnesota GOP leaders seek peace with party's anti-establishment wing

Who is Republican Lisa Demuth, Minnesota's first House speaker of color?