Providers are retrofitting buses, holding clinics at mosques and scheduling old-school house calls to bring COVID-19 vaccine to at-risk people who otherwise might get missed in Minnesota's rapid expansion plan.

While the state this week opened vaccine access to all 4.4 million Minnesotans 16 and older, the latest data on Friday showed disparities in minority groups that have suffered higher rates of COVID-19 hospitalizations and deaths and more work to do in protecting people of all races who are vulnerable because of their medical conditions.

People of color and public housing residents in south Minneapolis have struggled to gain access even though many are at elevated risk of infection and severe illness because of their front-line jobs and multigenerational homes, said Ramla Bile, a board member of the Seward Neighborhood Group, which lobbied for three vaccine clinics in local mosques next week ahead of Ramadan.

"These are people who need protecting, who should have been prioritized," she said, noting that the clinics close to those residents were needed in the absence of a state strategy to target them.

Weekly racial equity data, released Friday by the Minnesota Department of Health, showed disparities in age clusters rather than across entire minority groups. More than 73% of white, Black and Asian senior citizens had received at least a first dose of vaccine in Minnesota as of March 27, but the rate dropped to less than 60% among Hispanic and American Indian seniors.

White younger adults have raced ahead under recent expansions in vaccine supply and access — 16.9% of white people ages 16-44 have received vaccine compared with 9.8% of Black people in that age range.

An increase this month in COVID-19 activity is fueling concerns about such disparities because any remaining unvaccinated high-risk groups could suffer more hospitalizations and deaths. Nearly 82% of Minnesota seniors had received COVID-19 vaccine as of Friday — a risk group that has suffered 89% of Minnesota's 6,864 COVID-19 deaths — but death rates also have been higher among minority groups and non-elderly adults of all races with underlying health conditions.

Duane Shambour, 60, of Prior Lake lamented that vaccine access expanded to all Minnesota adults this week before he could get an appointment, despite working in a priority engineering job and having a heart condition that elevates his risk of severe COVID-19. Non-elderly adults with qualifying health conditions were added to the vaccine priority list for only 20 days last month before it was expanded to others.

"What happened after that was teacher's assistants and all these other young healthy people that I know were getting shots," Shambour said. "I was like, 'How are you getting a shot? You're young and as healthy as a horse.' "

Shambour is thankful that salty pasta for dinner forced him awake Thursday night and he found a random appointment online, but he said that isn't how vulnerable Minnesotans should gain access.

"There are so many people out there and they're at such high risk," he said. "This could take them down. We shouldn't have to sit on computers and chase this thing."

State infectious disease director Kris Ehresmann acknowledged the balance between vaccinating the neediest people first and making sure that every dose that arrives in Minnesota is injected in an arm quickly.

Many medical providers are focusing on higher-need patients first, she said, but the state also is in a race to vaccinate people before new, more infectious variants of the COVID-19 virus spread.

"It's a balancing act between making sure that people have access to vaccine but also making sure that we are continuing to be efficient in our vaccine delivery," said Ehresmann, speaking Thursday at a clinic set up for disabled patients of Gillette Children's Specialty Healthcare and their caregivers. "We're balancing several competing things."

Equity doesn't necessarily mean proportionate vaccinations across racial groups — not when minority members 50 to 64 have the COVID-19 mortality risks of white people 65 to 69, said Elizabeth Wrigley-Field, a University of Minnesota researcher who has closely tracked disparities in COVID-19 outcomes.

"If equity means that lower-risk white people shouldn't be vaccinated before higher-risk people of color, then Minnesota has a ways to go," she said.

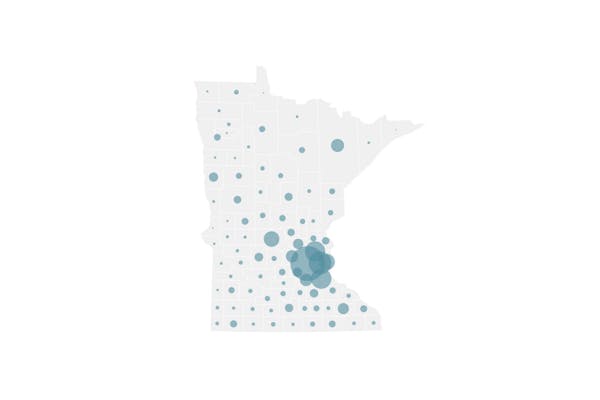

State health officials hope disparity data and demographic information from people who signed up on Minnesota's Vaccine Connector will identify underserved groups that can be targeted. The state is converting several Metro Transit buses into mobile vaccination units that will be dispatched later this month to underserved communities.

Allina Health arranged vaccine clinics in Minneapolis, St. Paul and Faribault for residents of targeted ZIP codes that are more vulnerable to the pandemic. The events provided 3,192 doses.

Federal approval last month of the single-dose Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccine also allowed Allina to begin offering vaccine in visits to homebound patients.

The system isn't efficient, as providers can get to only five patients per day, but it targets vulnerable senior citizens who have few options otherwise, said Dr. Josaleen Davis, who leads the program. "It's really the only way to reach people who are homebound to get them their vaccine."

Gary Skovbroten, 71, was relieved when Davis showed up last week with his dose, as he has limited mobility due to a degenerative muscular condition and is transitioning from a walker to a wheelchair to get around his home in south Minneapolis.

"Now that I have it, I really feel well-protected," he said. "If I had received COVID without any vaccine, I think it would have been pretty bad for me."

Jeremy Olson • 612-673-7744

Want to share info with the Star Tribune? How to do it securely

'Safe recovery sites' would offer syringes, naloxone and more to people using drugs. The plan could be in peril.

New Minnesota GOP leaders seek peace with party's anti-establishment wing

Who is Republican Lisa Demuth, Minnesota's first House speaker of color?