In an effort to stem the rise of nitrate pollution in rural Minnesota, Gov. Mark Dayton on Tuesday laid out a plan to balance farmers' use of fertilizer with the protection of groundwater and drinking water supplies.

The latest version, released by Dayton and Agriculture Commissioner Dave Frederickson, relies on both voluntary and mandatory measures to limit farmers' use of nitrogen fertilizers. It follows more than a year of heated debate among farmers, farm organizations, drinking water advocates and environmentalists, plus 11 public meetings and 820 comments.

Nitrate contamination in drinking water has emerged in the past decade as one of Minnesota's most vexing pollution problems. Dozens of community water systems have tested with high nitrate levels, and one in 10 private wells are seriously contaminated, mainly in southeastern and central Minnesota.

Yet curbing farm chemicals is not easy in a state where agriculture contributes $19 billion annually to the economy — much of it tied to the 800,000 tons of fertilizer farmers use on some 16 million acres.

"After receiving substantial feedback, and going through each and every one of them, we made significant revisions to the rule," Frederickson said. If it's adopted, by December at the earliest, "We will see far-reaching positive impacts in our state's water quality, while also recognizing the needs of the agricultural community," he said.

But leading Republican legislators quickly dismissed the new version, describing it in a statement as a "reactionary re-branding of a vastly unpopular rule." Lawmakers have already introduced half a dozen proposals to redefine its scope or restrict the Agriculture Department's power to implement it.

Dayton should abandon the effort and work "through the legislative process," said House Agriculture Finance Chairman Rod Hamilton, R-Mountain Lake, and Agriculture Policy Chairman Paul Anderson, R-Starbuck.

Environmental advocates, however, said the agency has listened to farmers and followed their advice, while taking steps to protect vulnerable drinking systems in small towns across the state that face rising threats from nitrates and enormous costs to protect their customers.

"For first time, they are proposing to do something specific for these highly sensitive areas," said Steve Morse, executive director of the Minnesota Environmental Partnership, which represents environmental groups at the Legislature. "We would like to go farther faster, but these are improvements."

In coming months farmers and citizens will have another chance to voice their opinions at public meetings that will be scheduled this summer.

Protecting sensitive soils

Anchored in the state's 1989 Groundwater Protection Act, the rule is Minnesota's first effort to regulate farmers' use of fertilizer.

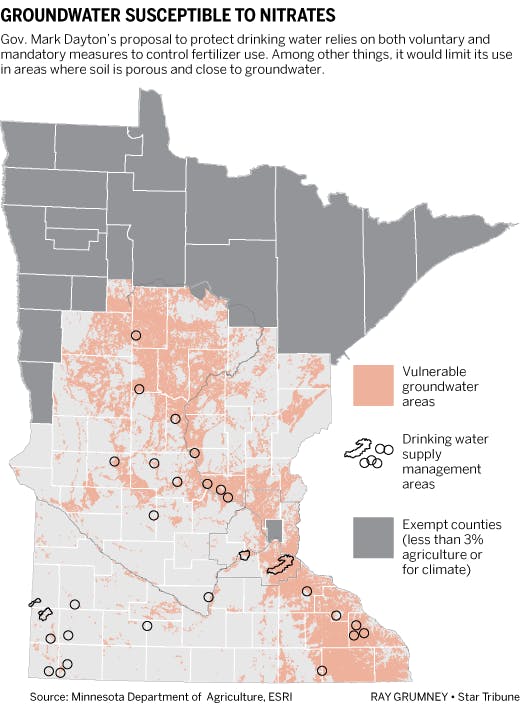

Underlying the plan is a statewide map of sensitive soils — a wide swath that stretches from the north-central part of the state, through the central sands region and the headwaters of the Mississippi River to the southeastern karst region. These areas are particularly sensitive to the nitrate contained in fertilizer, and they include public drinking water supplies for dozens of cities that are threatened by agricultural inputs.

The first part of the rule would restrict fertilizer use in those areas during the fall and winter months, when it is most likely to run off the land or leach into groundwater because there are no crops to take it up. Restrictions would also apply to drinking water "recharge" areas where nitrate levels are at 5.4 parts per million, slightly more than half of the legal limit allowed by state and federal health laws.

The limits were set because, in pregnant women and infants, nitrates in drinking water can cause blue baby syndrome, a potentially fatal condition that deprives babies of oxygen. Some studies have also linked nitrates to non-Hodgkins lymphoma and other health conditions.

But the Dayton administration carved out some exceptions after farmers complained that certain crops, such as winter grains, grass seed, and cover crops, require fall nitrogen. Nor would it apply to areas where nitrate leaching is minimal or counties where row crops account for less than 3 percent of the agricultural land — primarily northeast Minnesota and Ramsey County.

The second part of the rule would create local advisory committees in communities where nitrates in the drinking water supply areas reach 5.4 parts per million. The committees would help set best fertilizer practices to reduce contamination and encourage farmers in the area to use them voluntarily. If nitrate concentrations continue to rise after three years, the commissioner could require landowners to adopt the best practices, along with testing and educational programs. And if that hasn't worked after three additional years, the commissioner could require farmers to take further measures, which could include steps such as planting different crops, cover crops that hold nitrogen, or taking the land out of production.

Frederickson said the Agriculture Department will write another version of the rule after the next round of public hearings. It would be finalized and adopted by the end of the year, he said.

Josephine Marcotty • 612 673 7394

Want to share info with the Star Tribune? How to do it securely

'Safe recovery sites' would offer syringes, naloxone and more to people using drugs. The plan could be in peril.

New Minnesota GOP leaders seek peace with party's anti-establishment wing

Who is Republican Lisa Demuth, Minnesota's first House speaker of color?