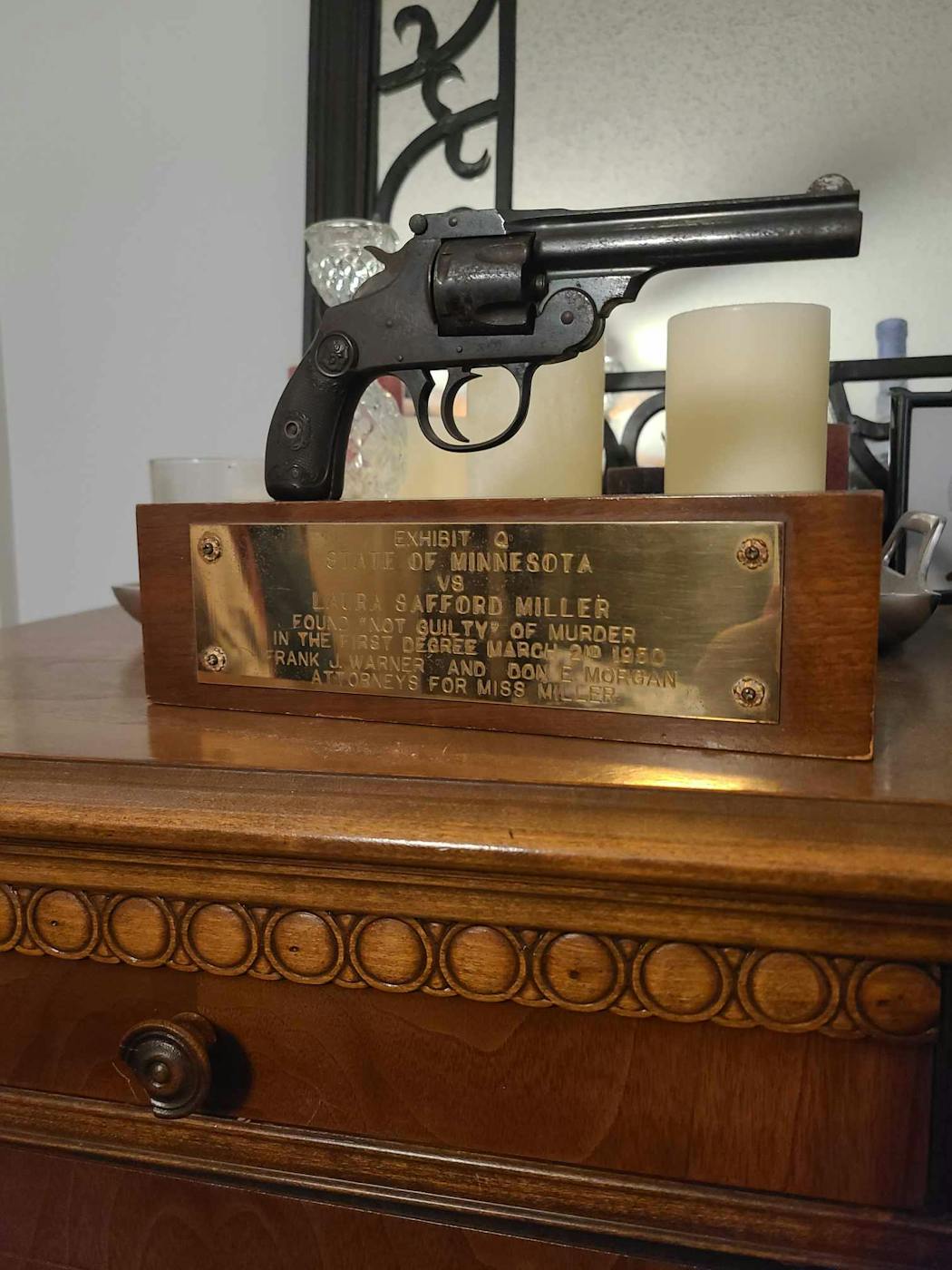

A mounted .38-caliber revolver sits on a dresser in Jim Nelson's Minneapolis home. The plaque identifies it as "Exhibit Q" and tells of a murder case in which Nelson's grandfather, attorney Frank Warner, successfully defended an alleged killer 73 years ago.

On a January morning in 1950, 23-year-old Minneapolis stenographer Laura Safford Miller pulled a sugar sack from a cedar chest and unwrapped the black handgun that had been in her family for years. She was pregnant and crying.

Grabbing her mother's Bible, Miller boarded an evening bus for the 60-mile ride west to Hutchinson, Minn. That's where she confronted a 36-year-old married lawyer, Gordon Jones, with whom she'd been having an affair for more than a year. She would soon testify that she was pregnant with Jones' child.

Just after 11 a.m. on Jan. 30, 1950, a woman living down the hall from Jones' office heard a gunshot, followed by scuffling and a second shot, and then a woman's cry: "Gordy, my darling, why did you do it?"

Found in a pool of blood, Jones died from a gunshot wound to his chest. Miller was arrested, handcuffed and taken to the McLeod County jail in Glencoe to await her first-degree murder trial three weeks later.

"The media circus surrounding the murder turned Laura Miller into a local celebrity," according to Brian Haines, executive director of the McLeod County Historical Society. "The trial was a spectacle, one where the judge allowed journalists, spectators and photographers to flood the courtroom."

Once the high-ceilinged courtroom in Glencoe reached its 200-person limit, remaining spectators were led across the street to the 550-seat Oriel Theater, where a loudspeaker blasted canned audio of the proceedings.

"The story behind the murder was a tale of romance, deceit and wrongdoing," Haines wrote on the historical society's website. "It was a backstory made for a Hollywood drama, and one that had captivated not just McLeod County, but much of the state."

Born in Illinois in 1926, Laura Safford was just eight days old when her mother died. Laura's aunt, Dell Miller, promptly adopted her and moved to Minneapolis when Laura was 12.

After graduating from Minneapolis West High School in 1944, Laura studied English and psychology at the University of Minnesota. Dell's heart condition forced Laura to give up school for stenography and bookkeeping jobs.

Laura insisted she was a a serious young woman who read three library books a week, according to a first-person story published in the Minneapolis Tribune shortly after Jones' death.

"I didn't have much time for dates" with boys who just wanted to party, she wrote, portraying herself as an innocent homebody swept off her feet by the charming attorney from Hutchinson.

Prosecutors countered with witnesses who debunked Miller's naive persona — detailing how she frequented night spots such as the Covered Wagon, a popular pioneer-themed steakhouse and bar in downtown Minneapolis.

That's where Miller first met Jones in August 1948, and quickly became enamored. They'd meet for dates when Jones came to Minneapolis, and she'd fill sheets of paper, "doodling" her fantasy signature as Laura Jones. She said she didn't realize until a year later that Jones was married with two children.

Miller took the stand on March 1, 1950, at times sobbing, screaming and collapsing. She testified that she became "intimate" with Jones in July 1949 and pregnant in November. Despite promises he'd marry her and help with the baby, Jones began to elude her. Once he hired a woman to pretend to be his wife and confront Miller, in hopes of scaring her away.

Frustrated, Miller testified she went to Hutchinson with her revolver and Bible, threatening suicide if Jones failed to "make arrangements." As he attempted to leave his office, she said, she pulled out her gun and pointed it at her stomach. As he tried to grab the gun, it went off.

Before the case could make it to the jury, Judge Joseph Moriarty threw out the charge and hinged his dismissal on Miller's "spontaneous" cry of "My darling, why did you do it?" — which the judge said proved she didn't plan to kill him. Instead, Moriarty ruled Jones died accidentally while trying to prevent Miller's suicide attempt.

The courtroom crowd applauded as Miller left a free woman. Laura told reporters that she'd be moving to Omaha to live with her brother and have her baby.

"I've done a lot of silly, foolish things — but the one thing important to me now is my baby," she said. "I'll never do anything like that again."

The 1950 census shows Miller living in Omaha — and then she disappears. She would be 97 today. Whether she got away with murder, we don't know.

But Haines heard a secondhand account from Hazel Graven, a McLeod County deputy who served as Miller's trial matron and told people later that Miller never cried or showed remorse in private.

"I guess we'll have to content ourselves with the idea that even though all the facts seem to be in order," Haines wrote, "there is always more to the story."

Curt Brown's tales about Minnesota's history appear every other Sunday. Readers can send him ideas and suggestions at mnhistory@startribune.com. His latest book looks at 1918 Minnesota, when flu, war and fires converged: strib.mn/MN1918.

Minnesota History: Ad man turned Paul Bunyan into a folklore icon

Minnesota History: James Griffin used persistence to blaze a trail for St. Paul's Black police officers

Minnesota History: For Granite Falls doctor who tested thousands of kids for TB, new recognition is long overdue

Minnesota History: A New Ulm baker wearing a blanket fell to friendly fire in the U.S.-Dakota War