Over the past month, the defense for three former Minneapolis police officers has asked jurors to consider an alternative theory as to why their clients did so little to help a man dying slowly in their custody almost two years ago: It's how they were trained.

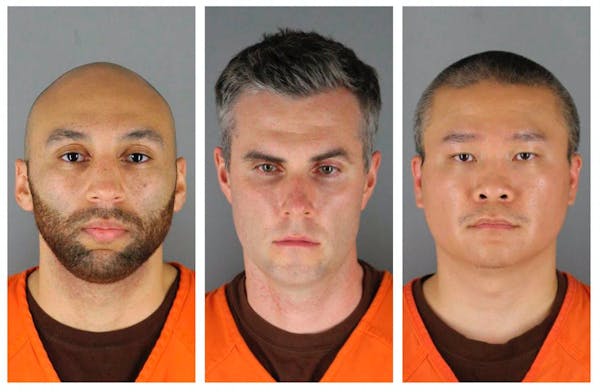

In the federal civil rights trial in St. Paul, attorneys for Tou Thao, J. Alexander Kueng and Thomas Lane have presented a case that shifts blame for George Floyd's killing away from the former officers and toward a paramilitary police department where the unofficial blue-line code supersedes the policy manual.

On Tuesday, the attorneys delivered closing remarks in a case where training is central to both sides. In separate final arguments, all three defense lawyers spoke at length about the training.

"A lot of this case went into training," Lane's attorney Earl Gray told the jury. "We like that. Because Thomas Lane followed training right to a T."

The charges say Thao, Kueng and Lane ignored their obligation to render medical aid to Floyd, even as Floyd repeatedly pleaded for air, cried out for his mother and fell unresponsive. Thao and Kueng face a second charge for failing to stop Derek Chauvin as he planted his knee in Floyd's neck for more than nine minutes. Chauvin, who was convicted of Floyd's murder in state court, pleaded guilty in this case last December.

The trial has offered a roving tour inside the culture of an organization known for its carefully vetted outward-facing image. The attorneys pored over training materials and cross-examined command staff and authors of the training curriculum. They showed videos from Thao's academy class featuring officers subduing people with a knee to the neck, similar to the maneuver used by Chauvin. They brought in expert witnesses, including former officers, to testify that a rookie "lacked the training and experience to recognize Mr. Chauvin's excessive use of force," let alone the authority to stop him.

During a cross-examination, Kueng's attorney, Thomas Plunkett, asked Inspector Katie Blackwell if the training is designed to imprint an "us vs. them" mentality toward the public they serve. Blackwell responded in the negative. Then Plunkett played a clip embedded in a PowerPoint for training she helped develop, which contained audio of Al Pacino from the movie "Any Given Sunday" delivering a warrior speech on the need to win a football game, accompanied by images of police in hostile situations.

"On this team, we tear ourselves and everyone else around us to pieces for that inch," says Pacino, in the video, which is apparently screened for police. "We claw with our fingernails for that inch."

All three officers also testified in the past week, giving their sides of the story publicly for the first time. Kueng and Lane, both rookies on the force, described their experience at the department's military-style police academy, where cadets are taught to stand at attention and address their superiors as "sir" and "ma'am.

"The chain of command is not to be breached — or else," said Kueng, adding he saw a fellow recruit who did breach it suffer a public berating from a superior.

"Sounds to me you were trained to walk and talk like a soldier," said Plunkett.

"Very much so," Kueng replied.

After graduation, they worked alongside field-training officers. Though their job title technically reads "officer," Kueng said they are still referred to as "trainees."

Lane told the court that trainees are expected to adopt the policing style of their field-training officers, whose recommendations to "the right people" will decide if they are fired or stay on the job.

Kueng said he believed his training officer could "unilaterally" fire him, even after the training period. Kueng's training officer was Chauvin. That's why, he said, he deferred to Chauvin once he arrived on the crime scene, despite department policy dictating the first officers on scene should be in command.

Former Minneapolis officer Gary Nelson, an expert witness for Lane, reiterated that the most senior officer is the one who takes control, no matter what the official line is. "It goes back to that hierarchy," said Nelson, who said the Minneapolis department does "share a lot of traits you would see similarly in a military organization."

The prosecution argued the opposite. They said the officers received extensive training on emergency medical response. They produced the officers' quizzes from classes showing they answered questions correctly about what to do when a person stops breathing. And even a group of bystanders with no training could see Floyd needed help.

"Fear of negative repercussions at work is not an exception to rendering medical aid?" Assistant U.S. Attorney Samantha Trepel asked Lane this week during cross-examination.

Correct, said Lane.

The officers also attended training on an official policy stating they had a duty to intervene if they witnessed excessive force by a fellow officer.

But the training on duty to intervene only consisted of one PowerPoint slide, an instructor reading policy and a much more egregious example of the type of excessive force requiring intervention, said Kueng.

Minneapolis police say they've implemented more extensive training on the duty to intervene in the aftermath of Floyd's killing. "Our team also partnered with nonprofit leaders to secure funding for an early-intervention system to proactively identify officers that need additional training," said Tara Niebling, spokeswoman for Mayor Jacob Frey, in a statement Tuesday. She said the mayor's 2022 budget includes funding for a new city attorney to review training materials.

In Lane's testimony Monday, he repeatedly told the jury he was following training from the moment he encountered Floyd. He said Floyd ignored his commands and refused to show Lane his hands, which set off "alarm bells."

"I think we've had scenarios almost exactly like that in the academy," said Lane.

Lane said he pulled his firearm and "escalated the situation to show how serious I thought it was."

"Were you taught that in the academy?" asked Gray.

"Yes," said Lane.

All three former officers testified extensively that they believed Floyd may have been suffering from excited delirium, a condition Kueng said could cause Floyd to "spring back to life" and become a threat once again, even after Floyd was unresponsive.

The department's training told officers that excited delirium is an extreme form of agitation that manifests as "superhuman strength," bizarre speech and aggressive conduct. A slideshow featured an image of officers pinning a man with their knees to subdue him. Lane said they were taught to restrain people in such condition in order to "keep a person from thrashing, hold them in place."

The Minneapolis Police Department said it has since stopped training about excited delirium, after the American Medical Association passed a policy rejecting the diagnosis as overly vague and too often used by police to justify use of force. A Star Tribune report recently found the police department was still training officers on this syndrome, and Frey has sworn to change the curriculum.

In his closing argument Tuesday, Thao's attorney, Robert Paule, remarked that all three defendants testified they independently suspected excited delirium with Floyd.

"All three officers came to the same conclusion," he said. "Rightly or wrongly, but at least it was based on their training."

Project 2025 platform proposal aims to allow mining in Boundary Waters watershed

Ann Johnson Stewart wins special election, giving DFL control of Minnesota Senate

Democratic U.S. Sen. Amy Klobuchar defeats GOP challenger Royce White

Gov. Tim Walz will return to Minnesota after Trump victory blocks him from becoming vice president