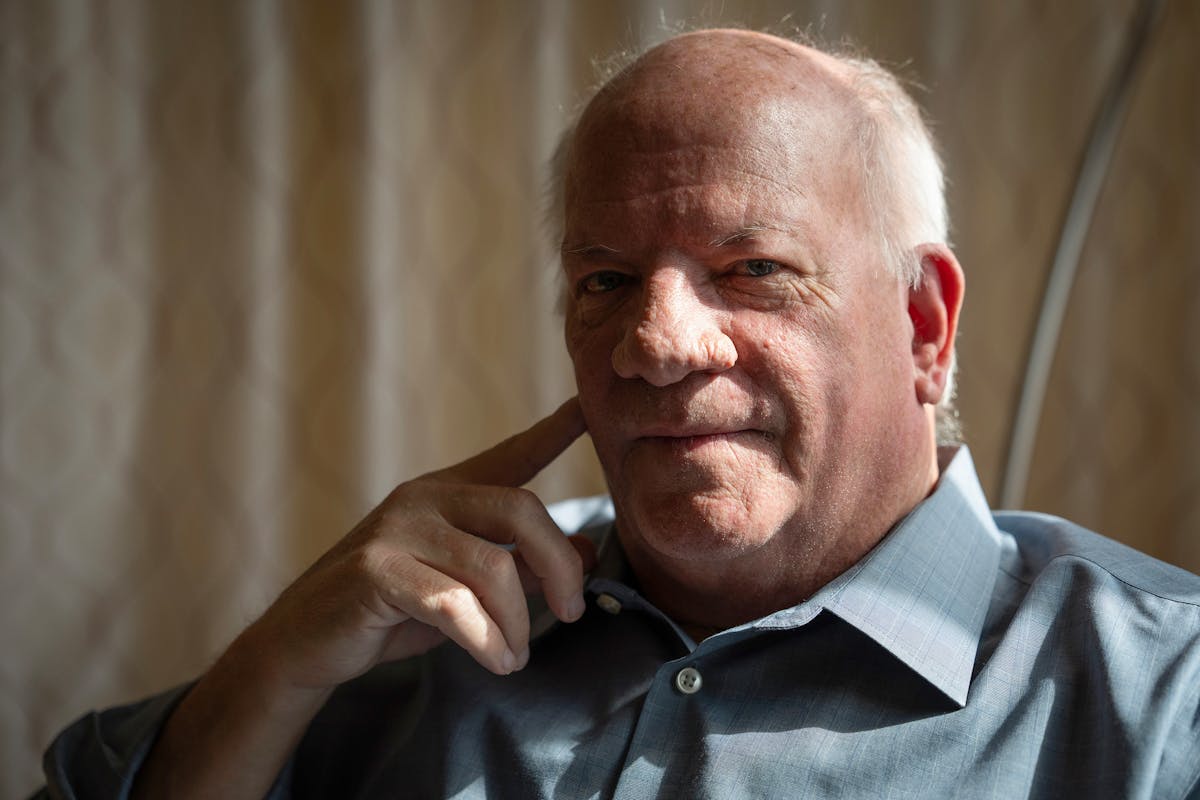

Depressed after his wife's death, this Minneapolis man turned to ketamine therapy for help

First came the music, soft and mystical, perhaps from the Middle East or Asia. My body began to feel heavy, like I was melting into the recliner. Then came the slow creep of unfamiliar but not unpleasant feelings and the taste of metal in my mouth.

It had been just a few minutes since Dr. Manoj Doss had injected me with a dose of the anesthetic psychotropic ketamine, a drug that has been successfully used in surgeries and other procedures for years. More recently, ketamine has found growing support in the mental health field because of its success in treating such psychological traumas as post-traumatic stress syndrome and depression and anxiety caused by lingering grief.

That's why I came, reluctantly, to the Institute for Integrative Therapies in Eden Prairie, the first in Minnesota to offer ketamine-assisted psychotherapy (KAP), part of the expanded use of mind-altering drugs to ease certain mental health problems. My wife, Ellen, had died in April 2023, and rather than get better, I found my mind increasingly trapped in a relentless cycle of bad memories and ruminations on her long illness and death.

Ellen had been my anchor — a spirited, funny woman who had been a pioneer in nonprofit fundraising. We had eloped to Mexico 36 years ago, and, knowing her life would be shortened by Type 1 diabetes, we traveled the world. Last spring, she insisted we go to Savannah, Ga., even though a doctor warned she could die on the trip. And she did.

After her death, I tried therapy and medications to fight depression and anxiety, but I only got worse. During an annual checkup, I completed a mental health questionnaire, which asked what gave me hope. "Nothing. My wife is dead," I wrote. Asked what would give me comfort on my deathbed, I sarcastically scribbled, "Salma Hayek." A doctor looked at my answers and asked a good question: "Do you own a gun?"

I needed to do something, but what? An old friend had told me about using psilocybin mushrooms under supervision in South America to recover from a breakup, and then I discovered that some Twin Cities clinics were using ketamine for similar results.

So, after a physical and blood pressure reading, there I was in a dark, cozy room with a blanket, headphones and a sleep mask waiting for the medication to kick in.

The heaviness turned to lightness as I began to feel as though my subconscious — my soul? — was rising out of my body. An onslaught of patterns and textures moved before me. Geometric shapes, a gauzy haze of white, pin-pricked dark skies. I floated through a landscape of bubble gum-colored terrain. Barbie Land?

As a writer, I struggled to create the narrative of what was happening to me, and I voiced frustration because I lacked words to describe my dreamscape.

"This is … weird," I recall telling Kristine Martin, the psychotherapist who accompanied me on my three-hour hallucination.

"It is weird," Martin responded.

"Are you still here?" I asked Martin. "Yes, I'm here," she said.

"Am I here?" I asked.

"Yes, you are here," Martin said. "So is Ellen."

Tears rolled down my face. "I know," I said. "I'm holding her hand."

Early research interrupted

Research into psychedelics for treating mental health disorders was done throughout the 1950s and '60s, but psychedelics were eventually adopted as party drugs. Psychologist and author Timothy Leary advocated that people use the drugs to "turn on, tune in and drop out." Though scientists saw promise in psychedelics, they were increasingly seen as an anti-establishment escape by the counterculture. President Richard Nixon saw that as a danger, and declared them a Schedule 1 drug, making them illegal.

"It wasn't done for public health reasons, it was done for political reasons," said Doss, the Eden Prairie physician. "Criminalizing them made it impossible to research and you were thought of as a kook. It would ruin your career."

That may be changing.

A nasal form of ketamine was approved by the FDA for clinical use to treat mental health problems in 2019. There are a handful of clinics in Minnesota now offering ketamine-assisted psychotherapy, and others that do ketamine infusions without the psychotherapy element. Doss estimates the number of patients who have benefitted from the treatments to be in the thousands in the state.

More therapies may be coming. In 2023, Minnesota created the Psychedelic Medicine Task Force to advise the Legislature on legal, medical and policy issues associated with psychedelic medicine. Doss' partner, Dr. Ranji Varghese, is a member of the task force.

Ketamine has gotten bad publicity through its use as a street drug. It was one of the drugs abused by actor Matthew Perry, who died from a combination of drugs. Like any drug, it can be abused and cause addiction or death. Use of the drug also came under scrutiny locally when some Minneapolis police officers were found to be instructing emergency responders to inject unruly or violent offenders.

Exactly how ketamine works is still being investigated. National Institutes of Health said the drugs are thought to dampen certain brain connections and activate some neurons in the brain while quieting others. It is believed to increase the organ's neuroplasticity, the brain's ability to adapt and change to meet new life experiences.

When a person gets trapped in a depressive mindset, their "default mode" creates chaos and confusion, creating depression and anxiety, Doss explained. That's where I was last summer.

A second journey

I paid $850 out of pocket for my first session, and $500 for the second, though some insurance companies are now covering or reimbursing patients for part of the expense.

For my session, Doss gave me an initial dose of 60 milligrams of ketamine, followed by two more doses of 30 milligrams to prolong the sessions. My dose was "mild to moderate," enough to create dissociations but not enough to sedate me. I was vaguely aware of my surroundings, yet clearly removed from my body.

Doss talks about the importance of "set and setting." The person needs to be ready for treatment and needs to take it in a safe place. After months of sometimes debilitating depression and thoughts of hopelessness, my mind was ready for a reset. The clinic proved to be a comfortable environment.

I had experienced psychedelics a few times in college, but it was recreational. Nothing like this.

I slowly came out of the experience and talked to Doss and Martin about my thoughts and feelings. I was unsure whether I had said things out loud, or only thought them to myself. A session with Martin a couple of days later helped me process the dream state I'd experienced.

Yes, I did tell Martin I was holding my wife's hand, and, apparently, I held my own hand as I said it. While some patients unearth long-buried memories during or after a psychedelic experience, I did not. I did cry for much of the three hours. I was a bit shaky afterward, and had a friend drive me home.

But the morning after the treatment, I was up at 6 a.m., hit the gym, wrote for two hours and went to breakfast, a pace I had not known for months. I had a sudden memory of Ellen telling a joke, and I laughed. I also was interrupted later that day by a memory of my father in the hospital for depression on Christmas Eve when I was a child. It was oddly reassuring; I had survived that, I will survive this.

When Martin asked what I was feeling, I said, "Clarity. Confidence. I feel positive."

Most important, the negative ruminations that roamed my brain — what I called the hamster wheel of doom — much of the day before my sessions were, and are, gone.

Some patients do several sessions of ketamine. I did a follow-up "booster" a few weeks after my initial shot. This time, the drug was given through an I.V. drip and I was accompanied by a nurse.

I did not cry. I did see Ellen again, briefly. She was holding the hand of a woman I had recently begun dating, and they were smiling. I later told Martin that I interpreted that to mean Ellen was giving me permission to move forward.

The other strange thing is that, unlike the first session, I heard lyrics for several of the songs. Scrolling through my brain were full stanzas and a chorus. They were uplifting and talked about getting through the darkness into the light. One sounded like Lionel Richie. OK, they were a little corny.

Shannon, the nurse who sat with me for the second session, said I was smiling and even laughing. At one point when the music soared, I put my hands in the air in triumph, like Rocky on the steps of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

After that session, I asked Doss why he chose songs with lyrics this time. He smiled.

"There were no lyrics," he said. "You made them up. You told yourself what you needed to hear. The subconscious is a powerful thing. There are caverns you have not even explored yet."

A new worldview

Ketamine does not work for everyone. Some patients report few or no effects. Others, however, see immediate results. It is not recommended for people who have had psychotic episodes because it can be a trigger.

Margaret Gavian, a psychologist who is part of the Psychedelic Task Force, has patients who have been treated with ketamine.

"What patients talk about is the relief they feel when nothing else has worked," said Gavian. She hasn't witnessed anyone having a bad reaction to the drug, but cautions that "people have to be ready because it's very intense. It can be freaky, to use a medical term. They are not for everyone."

Yet, she's also witnessed "people who are suicidal, who were suffering for decades, finally get some relief. It was really inspiring."

Mark Schneiderhan, board certified psychiatric pharmacist and associate professor at the University of Minnesota College of Pharmacy, said ketamine infusions can have an almost immediate decrease and effective relief of depressive symptoms in some patients who haven't responded to traditional antidepressant treatments, such as SSRIs.

However, he recommends ketamine be administered only in a clinical setting, where a patient's reactions and vital signs are monitored, and during a behavioral therapy session. Using the drug can cause dissociation (an out-of-body, disconnected feeling) which can cause panic and/or trigger disturbing memories "that can feel scary," he said. "That's when having a trained behavioral therapist at the bedside is so important."

Neither Schneiderhan nor the FDA recommends buying compounded ketamine off the internet or off the street. "There are no quality controls to ensure product safety," he said. "We don't know how it's compounded. What is the purity and dose consistency? There are all sorts of questions about it."

For his part, Doss describes psychedelics as "lenses. We are all stuck in our own existence, sometimes we need to have that worldview shaken."

He compares ketamine treatment to skiing down a long hill, carving the same path, with fears and doubts and ruminations, until you can't get out of the ruts. "This is a fresh set of powder to help you ski a new path. It's not a cure, it's a catalyst."

Did I have an epiphany? Seeing my wife twice was certainly close. Two months after my first ketamine exposure, I still miss Ellen and grieve for her loss. But something in the way I perceive the loss has shifted. The pain has lessened, and the memories are largely positive.

I'm still skiing downhill, but there's a new layer of snow.