'Death was everywhere': How a Minnesota nursing home descended into a COVID black hole

Desperate at ‘death ridge’

Leonard Novak was hard to miss as he zipped through the halls of his nursing home on a red electric scooter.

He had resisted moving to North Ridge Health and Rehab last year after suffering a serious bladder infection, fearing it would limit his freedom. But the barrel-chested, 91-year-old former utility worker soon became something of a celebrity there. Rising before dawn, he would slip on his favorite golf shirt and loafers, then get busy delivering coffee for residents too frail to walk, regaling them with stories of his square-dancing prowess.

His wife, Joann Eberhardt, two years younger and beset with advanced dementia, lived in another room on the same floor. She had lost the ability to talk or remember new faces.

Yet the couple was inseparable.

When the nurses were not looking, Novak would nudge his scooter behind his wife’s wheelchair and push her like a locomotive through the halls and outdoor courtyards, laughing and waving at fellow residents.

“Smokey,” his nickname from years of pipe smoking, also served as master of ceremonies at Friday night bingo, delivering a steady patter of play-by-play commentary. Many residents referred to the bingo room as “Smokey Novak’s Bar and Grille.”

“The worst thing you could do is give Smokey a microphone, because he was a showman,” said Mark Novak, his oldest son.

Then in April, Novak suddenly got sick.

When his children visited on a Sunday afternoon, they were shocked by how fast he had deteriorated. His labored breathing was audible from the hall outside his room. He lay ashen, his eyes fixed on the ceiling, unable to lift his head. Phlegm he constantly coughed up covered his gown.

Within hours of their visit, Novak was dead, the first North Ridge resident to succumb to the respiratory illness caused by the novel coronavirus.

In weeks, North Ridge became the site of the deadliest outbreak in Minnesota — and one of the largest nursing home outbreaks in the nation.

At least 40 residents there died from COVID-19 in the month after Novak's passing. By late June, 73 residents had died from the virus, records show, and 350 residents and staff had tested positive for it.

The toll was so devastating that some North Ridge employees began to refer to the sprawling, three-building brick complex as "Death Ridge."

David McCawley, 81, a former postal worker and avid fisherman who transformed his home into a haunted house every Halloween, died shortly after Novak. No one from North Ridge ever called to inform the family that he was dying of the virus, his daughter said.

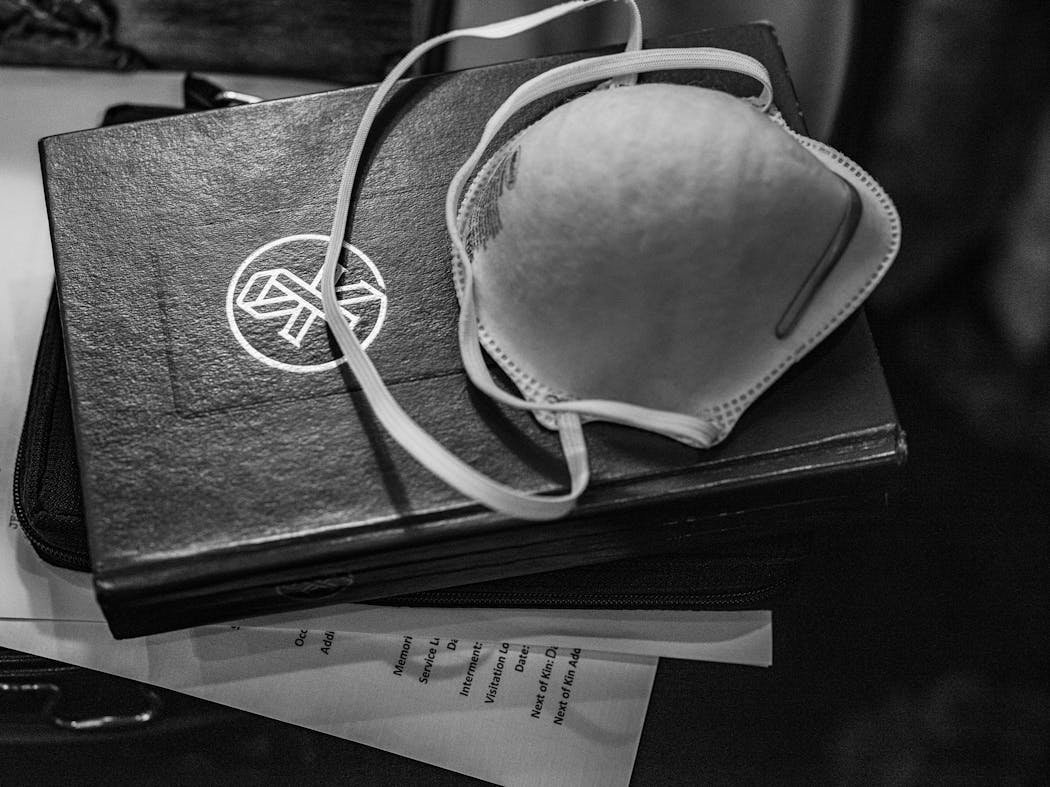

Joan Wittman, 88, a devoted member of the Jehovah's Witnesses who kept a marked-up Bible by her bedside, passed a week later. Wittman's daughter and granddaughter said they had no idea that dozens of North Ridge residents had already been infected before Wittman got sick. Had they known, they would have brought her home, they said.

Polly Van Waes, 89, a retired secretary who picked cotton and milked cows to pay for school clothes as a child growing up in Tennessee, died of the virus in May. Her daughter had to watch her mother's final, anguished cries from outside her window.

The terror that gripped the 320-bed nursing home is a stark portrait of the broader national tragedy unfolding with unrelenting, deadly force in institutions built to care for society's most vulnerable.

Across the country, more than 100,000 long-term care residents have perished so far this year. More than 780,000 have been sickened.

In Minnesota, COVID-19 has killed more than 2,800 men and women living in nursing homes and other long-term care facilities. Nearly 70% of the state's COVID deaths have occurred in these settings, one of the highest ratios in the United States.

The dead have left behind grieving children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren, many of whom still struggle with deep feelings of anger and guilt after trusting North Ridge and other senior residences to care for their loved ones in the twilight of their lives.

"We put my grandmother in that home with the understanding that you will take care of her, that you will do what we cannot," said Wittman's granddaughter, Genevieve Berendt. "That is the promise, and the promise was broken."

Ghastly stories of people dying alone in their rooms have terrified seniors and shaken the public's confidence in the government's ability to protect them from infectious diseases.

But the pandemic also revealed another painful truth: Many deaths in long-term care settings could have been avoided had state regulators, the federal government and nursing home operators heeded early warnings and taken basic safety steps as the outbreak began.

"Every day I imagine my dad dying alone in that room with no one by his side, and I question whether it had to happen that way," said David Novak, Leonard Novak's youngest son.

"So many of these deaths seem preventable."

Months before people started dying at North Ridge, reports of large and deadly COVID-19 outbreaks in nursing homes had already surfaced around the world.

"The warning bells were loud and clear," said David Grabowski, a professor of health policy at Harvard Medical School. "From the beginning, there was evidence that once [COVID-19] really gets going in these huge care facilities, there's just no way to protect residents."

In February, the World Health Organization reported that an alarming 22% of COVID-19 patients in China over the age of 80 were dying from the coronavirus — nearly six times the death rate for the population as a whole. The agency urged countries to create plans for protecting nursing home residents.

The virus was also cutting a deadly swath through nursing homes in Europe. In Italy, which has the world's second-oldest population, nearly half of those dying in nursing homes in the hardest-hit region of Lombardy either had the virus or displayed its symptoms, according to a survey by the Italian National Institute of Health.

As Europe imposed strict lockdown measures, the virus quietly infiltrated a large nursing home in suburban Seattle. The fast-moving contagion set off a deadly chain reaction at Life Care Center in late February that eventually claimed 46 lives and infected at least 60% of its patients.

Minnesota Health Commissioner Jan Malcolm referenced the Seattle outbreak at a March 4 hearing, telling state lawmakers that it "obviously gives us a great deal of concern in making sure we are doing preparation in long-term care facilities here."

But Minnesota was far from prepared. The pandemic exposed problems that have plagued the long-term care industry for decades, including lack of protective equipment, poor infection control and lax oversight by state and federal regulators.

In Minnesota, a Star Tribune analysis of federal health records found that 70% of Minnesota's nearly 370 nursing homes have been cited for lapses in infection control over the past four years — more than for any other type of health violation.

Many of the violations are rudimentary, such as workers not washing their hands or changing gloves as they move between patients. But in the face of a new, highly contagious virus, such lapses turned senior care facilities into tinderboxes.

In mid-March, federal regulators and the Minnesota Department of Health recommended a strict lockdown of long-term care communities. Within days, hundreds of nursing homes and assisted-living facilities across the state barred all but essential visits, canceled all communal dining and group activities and largely confined residents to their rooms.

But it was already too late. By April, the virus was beginning to spiral out of control in many of Minnesota's 2,100 nursing homes and assisted-living facilities.

More than three dozen residents of an assisted-living complex in Wayzata had to be evacuated by ambulance — and the facility shut down — after the virus infected most of its staff. In northern Minnesota, a large assisted-living center in Duluth called for emergency help from the National Guard after a quarter of its staff got sick and failed to show up for work. About 100 miles southwest in Brainerd, a nursing home recruited the emergency services of nine nurses from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) just to stay open.

As the crisis deepened, senior care facilities across the country were largely left to fend for themselves. They competed against each other for access to testing as well as lifesaving protective gear, including masks, gowns and face shields, while state governments bought up vast supplies and directed them to hospitals.

The U.S. government, which pays about $90 billion annually for the care of 3 million Americans who live in long-term care facilities, was slow to respond or offered conflicting guidance.

As deadly clusters of the virus escalated, the CDC released a "preparedness checklist" aimed at health care professionals, recommending that they review their infection-control and prevention procedures and begin procuring personal protective equipment.

The one-page checklist never mentioned nursing homes.

The federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) issued changing guidelines on testing and when to limit visits to nursing homes, but states were left on their own to decide how to implement those recommendations.

By early June, FEMA shipped boxes of protective gear to Minnesota nursing homes that turned out to be mostly useless: masks made from underwear and plastic gowns that resembled oversize trash bags, with no openings for the arms.

Yet as virus cases mounted, Minnesota's nursing homes would get a rude surprise when they asked the state for help.

The state Department of Health and the State Emergency Operations Center informed providers in April that its emergency stockpile of N95 masks was reserved for "hospital settings only" and that they should wait until their supplies had dwindled to "zero to three days" before requesting more gear.

As an alternative, the state encouraged nursing homes to consider using nonmedical cloth masks and to "connect with local communities for donations," according to state e-mails obtained by the Star Tribune.

To nursing home providers, the government's anemic response reflected a longstanding bias against long-term care. While nursing homes provide a wide range of complex medical care, including intravenous (IV) therapy and management of medications, they are often seen as less vital to the health care system than hospitals and intensive care units.

"We were treated like second-tier providers," said Annette Greely, president and CEO of Jones-Harrison Residence, a 157-bed nursing home in Minneapolis.

Across the state, reported resident and worker infections in senior care facilities soared from an average of about 20 per day at the beginning of April to more than 130 a day by month's end. Deaths increased tenfold during that same period, to an average of almost 19 a day.

But the state Department of Health, which oversees nursing homes, refused early pleas to provide more details about the scope of the outbreaks, such as identifying the number of cases and deaths at specific facilities. Some facilities shared that information with residents and their families, but many — including North Ridge — kept people in the dark for months. The secrecy prevented many families from taking steps to protect their loved ones.

State health officials scrambled to develop a plan to move more sickened residents from crowded nursing homes. Along with long-term care industry representatives, they expressed confidence in April in a proposal to create special "COVID support sites" — designated units or wings within existing facilities staffed with health care professionals trained to treat people infected with the virus.

In theory, the sites would alleviate pressure on senior homes and allow people to recover more quickly, officials said.

But the plan was quietly shelved. The Department of Health vetted some potential sites before determining that public opposition was too strong and the virus already too widespread for the plan to work.

Looking back, Malcolm acknowledged that the state was ill-prepared to protect residents of long-term care facilities. In fact, the state's emergency preparedness plan was focused on acute care hospitals and said little about addressing needs in long-term care communities.

"Just the fact that long-term care was really not ever a part of our kind of emergency management ecosystem … seems amazing in hindsight," Malcolm said in a November interview. "I hope this has been kind of a wake-up call for all of us."

The outbreak at North Ridge began quietly on March 24, when an unidentified staff person fell ill. The infected employee continued to work for another two weeks before testing positive, according to the Health Department. By that time Novak had already died.

North Ridge and other nursing homes were already in a state-ordered lockdown. Some, including North Ridge, took additional steps, such as moving COVID-infected residents to separate wings, enhancing cleaning standards and requiring daily screening of all direct care workers.

But dozens of North Ridge's 300 residents were showing visible symptoms of the virus.

Lisa Kostohris tested positive for COVID-19 in early April. Her blood-oxygen levels plummeted and she was sweating with a fever. She was moved into a wing of rooms on the first floor reserved for COVID patients. Fatigued, she spent the first several days drifting in and out of consciousness, fearful she was dying.

Unable to walk or lift herself out of bed because of multiple sclerosis, Kostohris, 61, could do little but stare at the cracks on the ceiling for hours. She desperately wanted to call her two sisters in Minnesota, who had lifted her spirits after she arrived at North Ridge three years earlier to recuperate from a bad fall and broken leg. But she had no phone or internet service in her room and said her repeated requests for a phone were ignored.

When Kostohris pleaded to be shifted from her bed to her wheelchair, staff told her it would be too dangerous, she said.

Trapped in her bed, Kostohris became increasingly alarmed by the frenetic scenes outside her room. At least once a day, she recalled, she saw staff wheeling corpses in body bags toward the building's exits. Others who showed signs of infection were left on stretchers in the hall. At night, the periodic moans and coughing of sickened residents kept her awake, she said.

“I had been in this man’s room with COVID for weeks, caring for him, and no one had bothered to say anything to me?”

She begged to be tested again, hoping that a negative result would get her moved off the unit, but was told that testing supplies were inadequate.

"People kept dying all around me, and I just wanted to get out," said Kostohris, who spent 30 days confined to the same bed in the isolation unit. "I kept thinking, 'Oh, my God, will I be next?' "

Without proper infection controls, nursing homes and assisted living facilities can be a fertile breeding ground for an infectious virus. Staff and residents dine and socialize in the same rooms. Shared rooms are common and people sleep close enough to hear each other breathing. At North Ridge, about a third of rooms are doubles, meaning a mesh curtain serves as the only barrier between one resident and the other. In some of the building's oldest rooms — which date back to 1966 — four residents share a single toilet and bathing area.

Staff members move from room to room, providing intimate care — such as bathing, dressing and toileting — that requires constant physical contact. Doorways are kept open to the bustling hallways, enabling nurses to come and go at all hours.

Harry Pratt, who lives on the facility's second floor, said in July: "This place is a giant petri dish." The 70-year-old retired surgical technician and former pastor was transferred to the COVID unit in early April with mild virus symptoms, including fatigue and shortness of breath.

He looked around and was shocked that many nursing assistants were not wearing basic protective gear such as masks and eye protection as they moved about the hallways.

The unit was so understaffed, he said, that it would take up to three hours for workers to respond when Pratt or his roommate pressed their emergency call buttons.

Early one morning, Pratt noticed that his roommate's coughing and labored breathing had suddenly stopped. Alarmed, he frantically pressed his emergency call button. By the time nurses arrived, the man was dead. Pratt watched as staff wheeled the body out of the room and replaced the soiled bedsheets. Later that morning, Pratt said, another resident infected with the virus was placed in the same bed where the man had died hours earlier.

"It felt heartless, like they were just moving bodies around," Pratt said.

Fearing that he would be reinfected with the virus, Pratt found a bottle of disinfectant and began scrubbing surfaces on his side of the room. His daily cleaning included the toilet and sink that he shared with three other men, he said. Pratt became so frustrated by staff not wearing proper protective gear that he posted a handwritten sign outside his door, demanding that all visitors wear masks.

"They were shuffling people in and out of rooms every day, and infection control didn't appear to be a priority," he said.

From their first-floor windows at North Ridge, Michael and Kathy Johnson watched the ambulances and hearses pull up to the door of the brick complex and depart — sometimes with two bodies at a time. Even for a nursing home, the couple recalled thinking, an unusual number of people were falling ill and dying.

Yet the Johnsons, recuperating from near-fatal injuries sustained in a car accident, said staff members frequently entered resident rooms without protective gear and many residents still wandered the hallways without masks.

When the Johnsons asked why so many people were dying, North Ridge employees declined to answer, citing patient confidentiality.

Their care deteriorated as the situation at North Ridge worsened.

Kathy Johnson said she sometimes had to wait for hours after ringing her emergency call button for someone to change bandages on her stomach. Sometimes, no one came, she said.

Michael Johnson, a retired pipe fitter, said that he was left on a bedpan for so long — more than two hours — that his legs went numb. One evening, after hours of waiting to be transferred to his bed, he rolled himself through the hallways in his wheelchair looking for help. Finally, he discovered a half-dozen staff members sitting in a conference room, putting together a 300-piece wildlife puzzle while patients rang their call buttons, he said. Furious, Johnson said he tore apart the puzzle and scolded the staff for ignoring their duties.

By now, the virus had overwhelmed North Ridge and the death count rose almost daily. On April 18, at least five residents died of the virus, according to death certificate records. A week later, five more passed away over a 24-hour period. In a single week in late April, at least 15 residents died from COVID-19, records show.

"It felt like death was everywhere," said Kathy Johnson, 72, a former hospital nursing assistant. "We could see hearse after hearse, and we began to wonder if we would be next."

Wendy Dyer, a longtime nursing assistant, shared their fears.

Dyer, who is 50, had started work at North Ridge early in the year. The larger facility offered her an opportunity to work more regular hours, which she hoped would make it easier to care for her ailing mother at home.

By late April, she said, supervisors were asking her to work extra hours to fill in for staff who were not showing up for work. No one explained the absences.

"People started to disappear," Dyer said.

As the threat of the new virus mounted, North Ridge in mid-April began accepting new residents already infected with COVID-19. One by one, they were wheeled through the front door, up the elevators and down the long corridors, Dyer said. Some traveled through the complex without face coverings, she said, and there was no separate entrance for newly admitted patients with the virus.

The new patients were moving into a nursing home that was falling deeper into turmoil as it struggled to contain the virus' spread.

Earlier that month, a Health Department investigator noted that new virus cases "have blossomed" at North Ridge and the facility "seemed very overwhelmed" by regulatory oversight calls from the agency, according to dozens of e-mails obtained by the Star Tribune through public records requests.

Even though it was voluntarily taking on more infected residents, a Health Department nurse specialist said that "North Ridge is in a staffing crisis" and was missing 117 of its 500 staff because of the virus, according to an April 16 e-mail.

Cases were growing so fast that North Ridge established a second wing for COVID residents, but soon had a "sizable development of COVID" outside of those wings, e-mail records show.

By April 20, North Ridge was pleading for assistance from the Department of Health, saying it "will not make it the next 72 hours" without more staff.

Meanwhile, staff were raising alarms with the state about being asked to work while sick and without adequate protective gear. A health care worker who stayed home after experiencing chills was told by North Ridge, "Oh no, that's not how it works, you should come to work," records show.

In another case, a worker complained of being asked to work "in both the COVID areas and the non-COVID areas" of the facility. An epidemiologist at the Department of Health responded by saying it was "not ideal, but it might be the only option."

Yet the admissions continued. Federal health records show that North Ridge admitted more than 40 COVID patients from hospitals and other long-term care facilities by the end of May, and 171 such patients by November.

Like many nursing homes, North Ridge had a financial incentive to accept patients with the virus. The new arrivals helped fill the financial void left by residents who had died from the virus, as well as fill beds left empty because fewer people were coming through nursing homes to recover after surgeries.

There was another incentive: Nursing homes are paid significantly more — up to $800 a day — under Medicare for new patients who require short-term stays than people with mild symptoms who stay longer, according to public health experts.

Austin Blilie, vice president of operations at North Ridge, declined requests for an interview. But in e-mailed responses to questions from the Star Tribune, he said the admissions were driven by a "desire to help our community and state in this time of great need." He also said that the spread of the virus was largely contained by the end of April, with new cases coming from people admitted from hospitals and other facilities.

"From day one, North Ridge has been vigilant and proactive in containing the virus spread within our community — because we understand the stakes, and we take seriously our responsibility to those we serve and to our community," Blilie wrote. "From the beginning we have had fully implemented infection control measures, ensured full [personal protective equipment] utilization for our caregivers, and we have separated positive or suspected positive residents in a dedicated COVID-19 unit."

The scene inside North Ridge was taking its toll on nursing assistant Dyer. After work, she would carefully remove her nursing scrubs in the entrance of her apartment building in Fridley, then dash upstairs and shower to avoid contaminating her mother, who has advanced dementia and is bedridden.

"In my 30 years of work as a caregiver, I had never seen so much death," Dyer said.

There had been warning signs in the months and years leading up to the pandemic that North Ridge might be unprepared for a highly contagious and lethal virus.

Dozens of government inspection reports dating to 2017 paint a disturbing portrait of a facility that repeatedly put its residents in harm's way. Pressure sores were left to fester untreated for so long that they bled. Emergency call buttons were so poorly staffed that residents often had to wait hours or call 911 for help. Bedridden patients went weeks without being bathed because of inadequate staffing. Rooms smelled of urine and mildew, and outdated food was left in the facility's kitchen, according to state and federal inspection reports reviewed by the Star Tribune.

In one case, a resident with cancer was found dead on the floor of his room, the victim of an overdose after a North Ridge nurse mistakenly administered 20 times the resident's prescribed dose of oxycodone, a painkiller, according to a 2017 state investigation. The nurse told investigators she did not verify the dose because she was "very busy with multiple patients" at the time.

As profits soar with ownership change, so do violations

Former employees and residents say the problems began in 2014, when its nonprofit owner sold North Ridge to Mission Health Communities for $40 million. The private company is owned by a Tampa, Fla.,-based private equity firm.

The buyout reflected a broader shift in the senior care industry. A decade ago, a growing number of nursing homes were selling to for-profit investors drawn to the industry by the aging of the baby boomers and the reliable stream of government funding through Medicare and Medicaid.

The trend worried patient-care advocates. For-profit nursing homes were found to have more health-code violations and lower staffing levels than nonprofit facilities, according to studies by the federal Government Accountability Office. Health researchers have also found that for-profit nursing homes were less prepared for the coronavirus pandemic. Nursing homes that reported severe shortages of personal protective equipment during the first several months of the pandemic were more likely to be for-profit, part of a chain, and to have COVID-19 cases among residents and staff, according to a study published in August in the journal Health Affairs.

Several former North Ridge employees and administrators said they noticed immediate changes after the new owners took over. Mission Health brought in outside contractors to prepare meals, clean rooms and provide physical therapy for residents rather than using in-house staff, according to facility financial statements.

Those changes and others delivered a significant boost to North Ridge's once-flagging financial fortunes. The nursing home went from losing $1.3 million in 2013 to making a $227,000 profit the following year under its new owners. Over the next four years, its profit per resident would increase 12-fold, from $2.02 to $24.43, or $2.3 million, according to annual financial statements.

Yet, as profits surged, North Ridge had more difficulty complying with health and safety standards.

Since 2017, the nursing home has racked up more than 80 violations of federal health and safety standards. On two occasions, federal regulators suspended payments to North Ridge — a rare punishment meted out to nursing homes that fail to fix recurring problems. As recently as February, North Ridge remained on a federal government list of 450 troubled nursing homes. It had been on that watch list for three years — among the longest of any nursing home in the nation.

Breakdowns in infection-control protocols were a perennial concern.

In late 2018, an elderly resident developed severe pressure sores after North Ridge staff failed to reposition her often enough. The resident's open wounds were left untreated for so long that they became badly infected and bled visibly, state health inspectors found. Earlier that year, another female resident was rushed to the hospital with sepsis, a bloodstream infection, as well as a urinary tract infection and severe weight loss. The cause was a badly infected catheter that North Ridge staff had failed to monitor, according to a state Department of Health investigative report.

In state surveys, North Ridge employees and residents spoke openly of the facility's health and safety problems. "It is about profit here," one unidentified staffer told inspectors in late 2018. Other employees said they were overworked and expressed guilt that residents were not being cared for adequately. "Sometimes the residents are so helpless that you just don't know what to do or where to begin," said an unidentified staff person in a 2018 state inspection report.

In June 2019, state Department of Health investigators found that the facility lacked a system for responding to emergency call lights — which are used by many bedridden and frail residents to call for help. One resident with Parkinson's disease activated an emergency button 58 times over a six-month period without ever receiving a response, inspectors found.

Connie Duffney, 68, who has chronic breathing problems and who once lived at North Ridge, said she got so frustrated that she set a timer on her watch to track how long it took employees to respond to her calls for help. Sometimes, several hours would pass before a nursing assistant arrived. Other times, no one came, even when she was seriously ill and vomiting, she said. On many occasions, she said, staff would walk in her room, turn off the call light and leave without addressing the problem.

"The emergency call system was a black hole," said Duffney, who left the facility in April 2018. "I could have been on the floor and they would have left me there to die."

Blilie said North Ridge takes seriously the importance of responding to residents, and conducts frequent audits of its response times to emergency call lights.

Yet the problems continued after the pandemic took hold.

In early March, state inspectors observed two staff members wash an incontinent resident and then handle the resident's bedsheets and clothing with the same soiled gloves. A family member told government inspectors that she sometimes cleaned the resident herself because she found feces smeared on her even after staff said she had been cleaned, according to an inspection report.

A month later, state health inspectors found more infection-control problems. North Ridge workers were observed not properly wearing masks and other personal protective equipment. Some placed the masks under their chins, while others covered their mouths and not their noses, inspectors found.

On April 20, more than a month after the CDC declared that masks should be "universally" worn by long-term care workers when there are COVID-19 cases in a facility, a North Ridge housekeeper told state inspectors that "today was [the] first day at this facility to wear face masks," according to the inspection report. There was still no training on how to wear masks, the person said.

"The facility failed to implement a comprehensive infection control program" that followed federal guidance, the surveyors concluded in the April survey.

North Ridge's Blilie said in an e-mail that there is "no correlation" between the infection-control violations that occurred earlier in the year and the COVID-19 deaths at the nursing home. State records show, he noted, that each of the violations was corrected soon after they were issued. Since May, North Ridge had also undergone 25 visits from the Department of Health, including four infection-control surveys, in which inspectors found no violations, according to Mission Health.

Blilie said there was "some confusion" in early April among employees over North Ridge's mask-wearing policy, which was corrected after the facility educated its employees on the importance of wearing masks properly.

"We now know that research indicates larger centers in areas with denser populations and higher infection rates were more vulnerable in the early months," said Cheri Kauset, vice president of customer experience and communications at Mission Health. "Sadly, that proved true at North Ridge. But we quickly and effectively responded, successfully mitigating the virus to the point where the state of Minnesota, the local hospital, and other nearby nursing care providers turned to us to care for people with COVID-19 in our dedicated unit, away from other staff and residents."

On May 7, amid pressure from lawmakers and elder-care advocates, Gov. Tim Walz’s administration unveiled a “battle plan” for combating the coronavirus in long-term care. It was two months after Minnesota reported its first known case of COVID-19 and one month after Smokey Novak became North Ridge’s first casualty.

"We are prepared to go very much on the offensive," Walz declared.

The five-point plan included more systematic testing of workers and residents, the distribution of more protective gear for health workers and ensuring "adequate" staffing levels at facilities hardest hit by the virus. Walz also pledged more active support from the state, including the deployment of the Minnesota National Guard to help with staffing and testing.

By then, more than 400 residents of long-term care facilities were dead. The virus had been detected in nearly 300 facilities.

Family members often had no idea where those infections and deaths were occurring. The state Department of Health refused to disclose facility-level information on the size and severity of outbreaks until June — and released the data only after a prominent lawmaker threatened a subpoena.

The secrecy, some family members argue, worsened the outbreak by robbing people of the opportunity to move their loved ones to safer places before it was too late.

Laura McCawley long ago promised her father, David McCawley, that he would never suffer or die alone. When he was moved to North Ridge last winter with advanced dementia, she repeated that pledge.

"I told him, 'Dad, I will always be here for you no matter what,' " she said.

McCawley would drop by North Ridge regularly to check on her father and bring him home-cooked treats, including his favorite chocolate-chip cookies with root beer.

Then, early one evening in April, McCawley received a voice mail message from North Ridge stating that her father had been moved to the facility's COVID wing. The message said nothing about his condition. Desperate for updates, or even a chance to speak to her father, McCawley phoned North Ridge dozens of times over the next six days. But none of the calls were returned. Finally, on April 19, McCawley received the call she dreaded most: Her father had died.

"It feels like we were lied to," she said tearfully in September as she wiped leaves off her father's gravestone. "And that lie will haunt us the rest of our lives."

Kari Rable's mother was a resident at North Ridge when she became sick from the coronavirus in late April. Rable was alarmed that no mention of an outbreak was included in public health reports or communications from North Ridge management.

"I believe they had a duty to tell the public the moment they learned of a single case" of COVID-19 in the nursing home, Rable said. "By not doing so, they sent a message that these lives were expendable."

Her mother, Florence Van Mersbergen, was sent to North Ridge in February to recover from a bad bout of pneumonia. She was poised to leave in April when the virus struck.

After waking one morning, the 83-year-old former homemaker felt her legs buckle beneath her as she tried to rise from her bed. Feeling dizzy and gasping for air, she pressed the emergency call button several times. No one came. Finally, she grabbed her walker and slowly made her way to the nurse's station down the hallway from her room.

In between gasps of air, Van Mersbergen tried to convince the nurses that she had symptoms of the deadly coronavirus. Her appetite was gone. Her breathing had become faster and shallower. And she was coughing up brown phlegm. Most troubling, she had become so fatigued that she could barely stand.

"I said over and over again, 'I need help!' and 'I can't breathe!' " she said. "But no one would listen."

Van Mersbergen said nurses refused her repeated requests to be tested for COVID-19. Panicking, she called her daughter on her cellphone and described her symptoms. Rable, a high school teacher in Champlin, was so alarmed that she frantically called every supervisor and staff member she knew in the facility — 24 calls in total — but every one of the calls went unanswered, she said.

Meanwhile, Rable noticed that her normally levelheaded mother had become incoherent, sometimes sobbing on the phone.

"I knew that we had to get her out of there — right away," Rable said.

Rable called 911 and begged paramedics to take her mother to the hospital. There, doctors discovered that Van Mersbergen's oxygen levels were so dangerously depleted that she needed to be put on a special machine to keep her airways open. The hospital tested Van Mersbergen and the results came back positive for COVID-19. It took her several weeks to recover and be transferred to an assisted-living facility in Brooklyn Park.

The experience still haunts her. In recurring nightmares, Van Mersbergen is gasping for breath and crying out for help while people walk by ignoring her pleas.

"You can't understand the terror of not being able to breathe until you experience it," she said, her eyes wet. "I would not wish the experience on my worst enemy."

In May, North Ridge administrators began rolling out a series of measures to contain the virus’ spread, which had already claimed 40 lives. The nursing home began weekly testing of all residents and staff and held daily clinical team meetings to evaluate the health of every resident and employee who tested positive for the virus.

It also had imposed a lockdown during the early days of the pandemic that was so strict that residents were not allowed to step outside the building without approval. And resident Charles Hilton soon learned the facility would break federal law to enforce it.

Hilton, 60, had moved into North Ridge in late 2019 to recover from a serious leg injury. After the pandemic hit, North Ridge distributed fliers throughout the complex warning residents that they would not be allowed to return if they left the building without permission.

When the burly theater actor and retired assembly line worker briefly stepped outside the building to have a friend read his mail, staff refused to allow him to return to his room. He reminded them that he was unaware of the new policy because he lost his eyesight in 1996 and could not read the fliers.

"I just couldn't believe they would kick a blind man to the curb like that, with nowhere to go," said Hilton. "There was no sympathy."

He spent a painful night on a wicker chair in the building's lobby, pleading with passing staff members to let him return to his room to grab his diabetes and blood pressure medications. But they repeatedly refused, he said. The next morning, nearly 16 hours after he was locked out, a fellow resident lent him a phone. Hilton called Metro Mobility, the public transit service for people with disabilities, to drive him to the Salvation Army homeless shelter in downtown Minneapolis. The next day, Hilton's friend went to gather his belongings and found them dumped in North Ridge's front lobby.

The state Department of Health investigated and determined that North Ridge violated federal laws that restrict nursing homes from abruptly evicting patients. Investigators also discovered that a woman with paraplegia was evicted illegally from North Ridge weeks before Hilton was kicked out. The woman, who is not identified in government reports, left the building in a wheelchair to give bags of laundry to a relative waiting in the parking lot. She was not allowed to return to her room. With nowhere else to go, she called a taxicab to a nearby hospital, according to a state investigative report.

As with dozens of previous citations against North Ridge, federal and state health regulators did not impose a fine or a penalty. The only requirement was that North Ridge submit a plan for correcting the violation.

North Ridge has accumulated $117,000 in fines since 2017 but has not been fined for any of the health and safety breakdowns flagged by government inspectors since the start of the pandemic.

This summer, amid mounting criticism over its handling of COVID-19 in nursing homes, the Trump administration announced that it had issued more than $15 million in fines to nursing homes during the pandemic for infection control violations and failure to report COVID cases. But taken together, the fines amounted to just $4,400 per nursing home and totaled less than a week's worth of Medicare disbursements to the industry.

"It's the equivalent of a traffic ticket," said Eilon Caspi, a gerontologist and health research professor at the University of Connecticut, of the fines. "They are meaningless as a deterrent."

The new measures undertaken at North Ridge did little to ease the anxiety felt by residents like the Johnsons. Even as deaths mounted, the words “coronavirus” and “COVID-19” were rarely spoken inside North Ridge, say current and former residents.

"They tried to pretend it was business as usual even when people were dying," said Dyer, the nursing assistant.

Blilie said the nursing home "takes pride in our transparency," and made consistent efforts to communicate with residents and families. Those included calls to families in early April, followed by weekly written updates throughout the month. In May, the facility transitioned to daily written and verbal communications with families and residents and posted COVID-19 updates on its website, he said.

He noted that tracking cases and deaths was difficult in the pandemic's early weeks because COVID testing was not readily available.

"This is a difficult time for everyone, and we are doing everything we can to keep our residents and their families informed," he said in a written statement.

Yet many families and others who relied on communications from North Ridge said they had no idea that North Ridge had a full-blown outbreak — or even that residents were dying.

In a May 13 message to residents and families, North Ridge said that two residents had died from COVID-19 and 80 had tested positive for the virus. Both numbers were wildly off the mark. In an e-mail to the Star Tribune a week earlier, North Ridge said that 44 residents had died from the virus and 139 had tested positive.

A day later, members of the Minnesota National Guard arrived on site to begin several rounds of COVID-19 testing. Yet residents and families were never told of the alarming results. State records show that 50 workers at North Ridge, or roughly one-fifth of staff tested on May 14, were infected by the coronavirus. Another 26 residents also were found to be infected over three days of mass testing by the National Guard, state records show.

Michael and Kathy Johnson's son, Jeff, said he scrutinized every e-mailed update from North Ridge. By May, he said the messages appeared to contradict the reports he was receiving from his parents, of dead bodies being wheeled out of the complex at all hours of the day.

"There is no question that [North Ridge] gave a false impression that the situation was under control," said Jeff Johnson, a youth gymnastics instructor from Maple Grove. "The virus was never under control."

“This administration knew even before the pandemic arrived in Minnesota that it would hit our seniors the hardest.”

Fearing they were in a race against the virus that they would ultimately lose, the Johnsons resolved to speed up their recovery from the car accident. Much of Michael Johnson's upper body was still encased in a cast, but he began to do daily leg exercises to build strength in his lower body. He found a large conference room where he could pull himself around in circles in his wheelchair, and he practiced standing while shifting from one leg to the other in his room.

By early June, weeks ahead of schedule, Kathy Johnson felt strong enough to leave the nursing home and her husband soon followed.

On the afternoon he was scheduled to be discharged, Michael Johnson was so afraid that a staff member might stop him that he broke into a sudden run in the lobby and charged by the front desk with his walker. Johnson kept running until he reached his son's pickup truck in the parking lot. He never looked back as they sped away.

"I felt like I had escaped with my life," he said.

The next morning, a Maple Grove police officer knocked on the Johnsons' door and informed the couple that she was following up on a report that Michael Johnson had "eloped" from North Ridge. After listening to their harrowing ordeal, the officer politely shook their hands and said she would not pursue the matter any further.

About the same time, Dyer began to rethink her commitment to North Ridge. Like the Johnsons, she had become convinced that administrators had lost control of the virus and it was "just a matter of time" before she would become infected and spread it to her disabled mother, whom she was still caring for in her one-bedroom apartment. Avoiding patients with the virus had become more difficult, she said, because it was not clear who among the residents was infected.

One day, a manager pulled Dyer aside and told her that a resident, who had paraplegia and was bedridden, had tested positive for COVID-19 two weeks earlier. No one had notified Dyer, who provided care to the sickened resident on her nightly rounds. In the meantime, Dyer, who has severe asthma, had been going from room to room, potentially infecting dozens of patients.

"All I could think about was, I had been in this man's room with COVID for weeks, caring for him, and no one had bothered to say anything to me?" said Dyer, shaking her head.

Soon after, an administrator at North Ridge gave Dyer an ultimatum: Either work on floors with COVID-19 patients or leave.

Dyer handed in her uniform and left.

"I feel for the families and for the ones who have the virus," Dyer said. "But I couldn't put myself and my family at risk of getting the virus."

No other nursing home in Minnesota experienced sickness and death on quite the scale that North Ridge did, but few were spared. The number of long-term care facilities with outbreaks nearly tripled between late June and early December from 459 facilities to 1,221, state records show.

Since the pandemic began, 20 senior homes in Minnesota reported 20 or more deaths from COVID-19, including six that had more than 30 deaths, records show.

At North Ridge, 94 residents had died by early December amid 495 resident and staff cases.

By then, according to death certificate records, nearly half of the residents who died there had some form of dementia, a condition that could make some residents unaware of the dangers of COVID-19 and the necessity for safety precautions.

As summer wore on, state measures appeared to be slowing the rapid spread of the virus in long-term care facilities. But while the pace of new cases and deaths was ebbing, North Ridge residents, family members and advocates for the elderly started questioning why the state Department of Health, which oversees elder care homes, did not act sooner to protect them.

Cheryl Hennen, Minnesota's long-term care ombudsman, said the Department of Health's slow response and decision to withhold information about the size and location of outbreaks — even as residents were dying — amplified the anxiety that many seniors were already feeling about the virus. Panicked seniors from across the state were calling her office, she said, because they did not know if the facilities where they lived had cases of the virus.

Said Sen. Karin Housley, chairwoman of the state Senate committee on family care and aging: "This administration knew even before the pandemic arrived in Minnesota that it would hit our seniors the hardest. … Yet they waited months, and many of our elderly died because of it. It's indefensible."

Malcolm said in a recent interview that state health officials communicated with long-term care providers "on day one" of the pandemic, but the agency's initial response was partly undermined by a lack of information and confusion about the nature of the virus. Early on, for instance, it was not widely known even among infectious disease experts that people without symptoms could be the most prolific spreaders of the virus.

Heavy staff turnover was another challenge, said Kris Ehresmann, the health department's infectious disease director. The state's effort to train and educate staff on infectious disease outbreaks, which intensified after the Ebola epidemic in 2014, was hampered by the rapid turnover of the long-term care workforce. At North Ridge, the turnover has accelerated, with 30 to 60% of its direct care staff departing each year between 2014 and 2018, state financial records show.

"We are constantly battling that challenge, that some of the work that we are doing has to be redone because of [staff turnover]," Ehresmann said.

“I’ve said ‘I’m sorry, I’m sorry,’ to her dozens of times ... I will live the rest of my life regretting that I put her in that place.”

Still, families who lost loved ones at North Ridge and some public health experts questioned the state's practice of allowing North Ridge to admit infected patients. Through summer and fall, North Ridge continued to accept dozens of COVID-19 patients from hospitals and other long-term care facilities, even while it was reporting a severe shortage of nursing staff and personal protective gear, federal records show. In reports made since May, North Ridge consistently told regulators that it had less than a week's supply of masks, gowns, gloves and hand sanitizer, federal records show.

Tamara Konetzka, a professor of health services research at the University of Chicago, said it is surprising that a facility as large as North Ridge did not undergo an extra layer of review before being allowed to take new patients with COVID-19. The state, she said, could have sent in "strike teams" of experts to evaluate whether North Ridge had adequate protective equipment and infection-control procedures.

"At minimum, nursing homes should be required to demonstrate they can handle an infectious outbreak before they take on new patients," she said. "We now know that many nursing homes were not prepared."

State Health Department officials said that admissions or transfers of COVID-19 patients to nursing homes are private business decisions. They said there is no evidence that any North Ridge residents caught the virus from someone transferred there. As of November, 38 of the 90 people who had died at North Ridge from COVID-19 were residents who had been transferred from other facilities, the agency said.

"While [North Ridge] had early challenges, they really worked hard and in close partnership with us to make improvements," Malcolm said.

Although the situation has stabilized at North Ridge, COVID-19 is surging again in long-term care facilities statewide, with more than 1,000 deaths and 15,000 cases since early October, surpassing the toll taken during the early months of the pandemic.

For many who could not visit loved ones in their last days at North Ridge, the guilt and anger have yet to lift. Final hugs and kisses were never shared, comforting words were never spoken. Compounding their grief is that many must mourn alone. The normal rituals of funerals and large gatherings have been postponed or limited to only the closest family members.

In the days and weeks following her mother's death, Julie Loftus would sit alone on her porch with the urn that held Polly Van Waes' ashes and talk to her in the tender drawl of her native Kentucky.

"I've said 'I'm sorry, I'm sorry,' to her dozens of times because I feel like I failed her," Loftus said. "I will live the rest of my life regretting that I put her in that place."

Loftus knew her mother had little hope of survival when she was transferred to North Ridge in late May. By then, she had already contracted the virus and her lungs had nearly collapsed. Loftus made one final request of North Ridge staff: "Please, please, I just begged them to make her comfortable, because I didn't want my mother to die in pain."

But Loftus became worried when North Ridge stopped returning her telephone calls. With visitors prohibited from entering the facility, Loftus climbed over a 6-foot wrought-iron fence to get a closer view of her mother's room. Once at her window, Loftus was horrified by what she saw: There was her mother, moaning in agony while grabbing her side like she had "been shot by a bullet," Loftus recalled.

Desperate, Loftus said she pounded on the window for 10 to 20 minutes before a nurse appeared and injected her mother with a shot of painkiller. Four days later, Van Waes died of respiratory failure from the virus.

"It was clear to me that they had forgotten about my mother," said Loftus, who lives in Crystal, just a few miles from North Ridge. "My one final wish — that she not suffer any discomfort — was ignored."

Kalia Machacek and her sister Kalisha Wiggins had resolved to keep their 68-year-old mother, Verlinda Fortney, out of a nursing home after she contracted COVID-19 this summer. Fortney, a longtime special-education assistant in north Minneapolis' public schools, had stayed at a nursing home three years earlier to recover from a diabetic emergency and the experience left her badly shaken.

But after she contracted the coronavirus and slipped into a prolonged coma, staff at Regency Hospital in Golden Valley recommended she be transferred to North Ridge. Fortney was still too sick to speak on her own or lift her arm to sign documents, so her daughters intervened. Shaken by reports that COVID-19 was rampant at North Ridge, the daughters pleaded with hospital staff to find a different facility. A social worker at the hospital insisted that North Ridge was the only option, and Fortney was sent there by ambulance against the wishes of her daughters.

Less than 48 hours later, Fortney died in her room at North Ridge. The sisters rushed to the nursing home at 1:30 a.m. and insisted on seeing her body. When they arrived at her bedside, they found her eyes were still wide open, they said.

"It all happened so fast," said Wiggins, sobbing. "The worst part is knowing that our mother's wishes were ignored."

In July, Machacek knelt by her mother's grave near Gary, Ind. She recalled how she loved listening to her mother's rich, deep voice as she serenaded her daughters to sleep at night. She held her smartphone to the sky and played a recording of "Wind Beneath My Wings" while reflecting on her mother's life and sacrifices as a single parent of three children.

"Verlinda was a forgiving person and I know she would want me to forgive," Machacek said.

But Fortney's death so traumatized Wiggins that she has resolved to leave Minnesota and never return. North Ridge is just 3 miles from her home and impossible to miss. Down her street is the drugstore where she picked up her mother's medications and the supermarket where they shopped together.

"It's difficult even driving these streets now," Wiggins said, her voice quivering. "Memories of Verlinda are everywhere. It's hard, very hard."

Five months after his death, about three dozen family members and friends — all wearing masks — filed into a small funeral home in New Hope, just 2 miles from North Ridge, to pay their final respects to Smokey Novak.

A small wooden box at the front of the funeral parlor held his ashes. His four adult children moved through the masked crowd slowly. They bowed their heads in silence as a stereo played the Lutheran hymn "A Mighty Fortress Is Our God." Notably absent was Novak's wife, Joann, who was unable to leave her room at North Ridge because of the lockdown.

"For me, Dad was a cheerleader," David Novak said in his eulogy, fighting back tears. "He was always there to cheer you on, no matter what you did and whatever your passion was."

His children recalled how much their father enjoyed getting to know other people. As a gas-line locator and repairman, Novak was known to hang around a job site long after the work was done, chatting with colleagues and nearby residents.

At North Ridge, Novak often spent hours in the rooms of fellow residents listening to them talk about their lives. He approached staff at the nursing home with the idea of interviewing people who lived there and compiling their personal stories in a large book filled with photographs. The collection, he imagined, would be passed down to future generations so the stories would never be forgotten.

"Dad knew that everyone there had a story and every one of those stories had meaning," said Brenda Nielsen, Novak's daughter.

It was Smokey Novak's last big project.

He died before the stories could be told.