Brittany Kjenaas and her husband are among the couples lucky enough to have a daughter in child care at Iron Range Tykes Learning Center in Mountain Iron, Minn.

The center is in such high demand, and options there are so scarce, that families living 20 to 30 miles away in Hibbing and Tower will time the births of their children with the 18-month wait for an infant care slot, owner Shawntel Gruba said last week.

Kjenaas said she and her husband earn too much to qualify for the state's early learning scholarships, yet barely get by with costs exceeding their mortgage, adding: "Unless something is done to lower the cost of child care, she will remain our only child."

This year, state leaders gave a big boost to low-income families struggling to pay for child care. Now the push is on to help middle-income parents.

A proposal for the coming legislative session aims to help cover costs on a sliding-scale basis for families earning up to $175,00, and it is being welcomed by Debra Messenger, director of All Ages & Faces Academy, a child-care center in St. Paul.

At a recent news conference, she spoke of calls she's received from parents eager to enroll their children and the silence that follows when she tells them the cost: "It is heartbreaking to have a mom who is excited to have found child care at all ... realize she will have to decline her new job offer because she cannot afford child care," Messenger said.

According to early-childhood advocacy group Think Small of Little Canada, the median Minnesota family with one infant spends about 21 % of their household income on child care, compared with the 7 % of income that the Economic Policy Institute (EPI), a nonprofit think tank, deems "affordable." EPI put the average annual cost at $16,087.

That is more than the cost of a year's in-state tuition at the University of Minnesota, said state Rep. Carlie Kotyza-Witthuhn, DFL-Eden Prairie.

She is working with state Sen. Grant Hauschild, DFL-Hermantown, on a bill to expand the early learning scholarships program to middle-income families — a proposal that at the time of the Nov. 30 news conference carried a price tag of about $500 million.

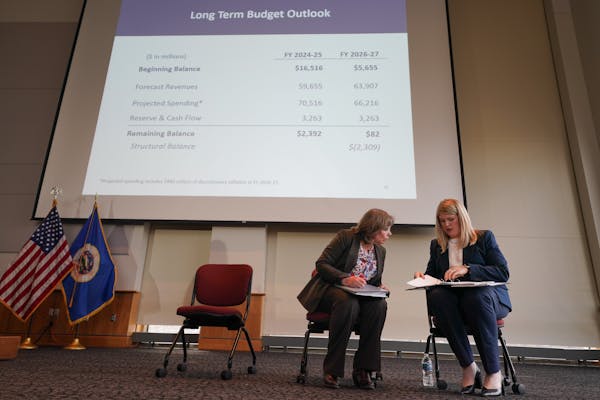

A week later, state budget officials predicted that lawmakers would have a $2.4 billion surplus in the coming session, but added a potential $2.3 billion deficit loomed in the next biennium. Republican leaders say that leaves little room for new spending.

Hauschild, who has held child-care roundtables in his district, said last week that work continues on the bill and he is eager to hear what budget forecasters say in February when lawmakers return to the State Capitol.

"I'm not going to stop bringing up ideas to help solve the big challenges we face," he said. "But I'm always going to be fiscally responsible when it comes to our budget."

This year and next, funding of early learning scholarships will jump from $70 million to $196 million a year. Think Small, the scholarships administrator in Hennepin and Ramsey counties, plans to dedicate much of it to giving low-income infants and toddlers access to richer, more consistent programming.

Minnesota also provides funding for a limited number of school district preschoolers.

Carson Starkey, a St. Paul parent, said his 4-year-old daughter has free preschool at the district's Nokomis Montessori North Campus. Good thing, he said, because he also has a 1-year-old in day care, and the combined cost could've topped $20,000 a year.

"That can be overwhelming and can drown a lot of young families at a time when they're just becoming established," he said.

Starkey's comments came during a legislative hearing in November, during which he also gave a shout out to child-care operators and staff members for the "invaluable work they do for our society ... helping to raise and educate our babies."

At Iron Range Tykes, Gruba said that the bond between staff and families is strong. The center is licensed for 90 children, but about 350 come and go, given not all are there five days a week and cancellations can lead to calls to families on standby.

"A lot of my staff and myself attend the children's events outside of here," she said. "We attend birthday parties. We're all very close."

Despite demand, she said, the center operates at a "very low profit margin," owing to mandates related to first aid and CPR training, and USDA food regulations, among other requirements. She said Gov. Tim Walz has been a great early-ed advocate, but the free meal program he championed for schools does not extend to child-care centers.

In January 2022, she raised rates, and saw a family of six pull three kids from the center. There always is a waiting list and the ability to fill the slots, but as a parent she feels "horrible" about making such moves. And it has been on her mind of late.

A new year will bring a new hike, she said, and she expects turnover again.

Want to share info with the Star Tribune? How to do it securely

'Safe recovery sites' would offer syringes, naloxone and more to people using drugs. The plan could be in peril.

New Minnesota GOP leaders seek peace with party's anti-establishment wing

Who is Republican Lisa Demuth, Minnesota's first House speaker of color?