Did German POWs really work on Minnesota farms during World War II?

Listen and subscribe to our podcast: Via Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Stitcher

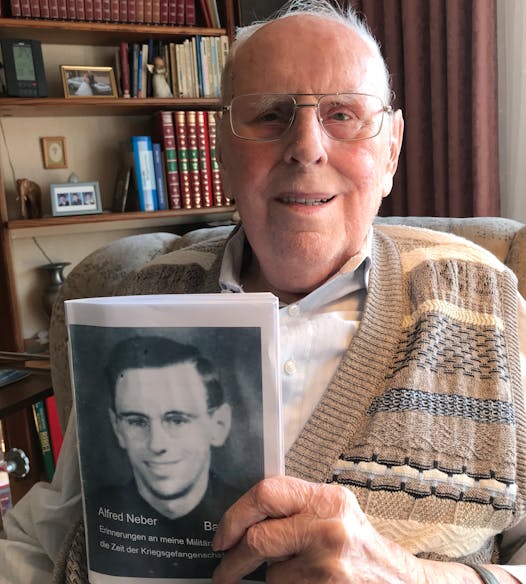

At age 95, Alfred Neber fondly remembers his stay in Minnesota 75 years ago — attending church, going swimming, as if on a typical Minnesota summer visit. But Neber wasn't a typical visitor, he was a German prisoner of war.

Neber was among some 400,000 Axis POWs captured during World War II and dispatched to 500 camps around the United States. The prisoners did work normally done by Americans, who were busy overseas fighting the prisoners' comrades.

Many Minnesotans are unfamiliar with this episode in history. A reader who requested anonymity asked Curious Minnesota, our community-driven reporting initiative, to look into it.

Thousands of POWs, mostly German and some Italian, worked in Minnesota between 1943 and 1946 (there were Japanese POWs in the country, but none in Minnesota). Experts can't pinpoint the number because they were constantly being moved around from a "base camp" in Algona, Iowa, and "branch camps" throughout Minnesota. Most did farm work but also logging, factory production and other jobs. Their employers paid the government 40 cents an hour, of which the prisoners received 10 cents to spend in canteens.

The camps weren't exactly brutal chain gangs. Many employers were friendly to the prisoners, fed them hearty meals, took them to county fairs, even invited some to spend the night with the farm families.

"One thing I remember with a smile is that we were allowed to go to swim in a lake nearby," Neber said, in an e-mailed interview translated by his son Ralph.

A farmer in Moorhead "bent camp rules by buying prisoners beer and taking them into town, including a trip to a movie theater and one to a local tavern," wrote Angela Beaton, a former graduate student at North Dakota State University in Fargo, in an article published by the Minnesota Historical Society.

"Midwesterners who worked beside them in the fields and the factories discovered they were humans, pretty much like themselves," said Michael Luick-Thrams, who has published several books on the subject, operates an information-packed website and briefly operated a museum in St. Paul.

Some had even more in common. Minnesota had a large German immigrant population, and many still spoke German.

"Sometimes they knew the same towns, knew the same people," said Dean B. Simmons, a teacher at St. Thomas Academy in Mendota Heights and author of "Swords into Plowshares: Minnesota's POW Camps during World War II." More conflicts arose among the prisoners themselves, Simmons said, particularly between those who were loyal Nazis and those who weren't.

Neber, who describes himself as anti-Nazi, now lives in a small German town near Heidelberg. He has warm memories of being in Howard Lake, Minn., at age 20. He spoke highly of a camp guard who let the POWs attend a German church on Sundays. And of the pastor who welcomed the ostensible enemies into his German-speaking flock and, after the war, sent Neber "a small care package with delicious food and sweets," he said.

An estimated 5,000 returned here after the war and became U.S. citizens, Simmons said.

Luick-Thrams said he heard about a Minnesota farmer who tried to lure a former POW back, promising, "I'll give you my farm and you can marry my daughter." No word on whether the offer was accepted.

---

If you'd like to submit a Curious Minnesota question, fill out the form below:

Read more Curious Minnesota stories:

Why do some major Twin Cities highways not connect directly?

Why hasn't Minnesota passed the Equal Rights Amendment?

Why do wild turkeys seem to thrive in the Twin Cities?

Why is Minnesota more liberal than its neighboring states?

When you flush a toilet in the Twin Cities, where does everything go?

Was Minnesota home to nuclear missiles during the Cold War?

How did Minnesota become known as the 'Land of 10,000 Lakes?