Minnesota lost 58 dairy farm permits in November, a devastating blow to a farm sector already drained by contraction.

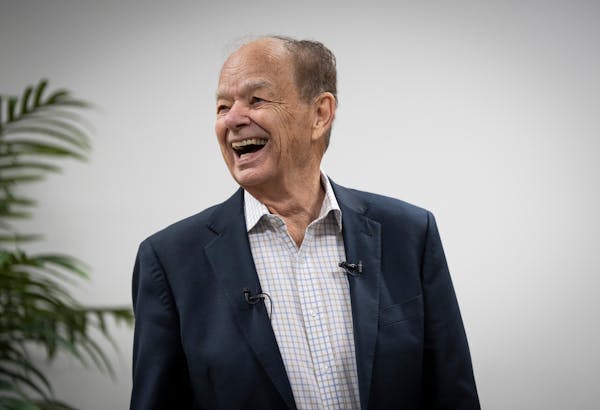

"We have some seasonality to this. In October, November and December, you'll always see some herds go," Lucas Sjostrom, executive director of the Minnesota Milk Producers Association, said. "But I have not seen [a monthly declines in permits] over 50 for a long time."

The end of the year is typically a time to see more farmers opt out of milking cows, either permanently or temporarily, as producers put up silage or feed for the coming year.

But Sjostrom says last month's numbers underscore the razor-thin financial margins for dairy farmers under a crush of economic pressures, such as high input costs and low commodity values, just a year after dairy enjoyed higher prices for milk, cheese and butter in the aftermath of the pandemic.

Sjostrom said at least farmers aren't going bankrupt. He credited safety-net programs such as Minnesota's Dairy Assistance, Investment and Relief Initiative for aiding producers during crashes in milk prices.

"I would guess Minnesota has, due to that program, the least amount of unplanned exits," Sjostrom said.

In sum, Minnesota has 146 fewer dairy farmer permits this Christmas than the state did at the beginning of the year, according to the Minnesota Department of Agriculture.

Overall, the state had a total of 1,825 permits as of Dec. 1, according to MDA. A decade ago, the state counted over 4,000 dairy farms.

The largest losses this year were in central Minnesota's dairy heartland. Stearns and Morrison counties saw 27 and 21 fewer permits in December than in January, respectively.

Counties in southeastern Minnesota's dairy belt — Fillmore (nine), Goodhue (six) and Houston (five) — also saw significant losses. A few counties in Minnesota saw small increases in the number of dairy permits, including Becker (two) and Aitkin, Winona and Swift (one).

The bitter news follows a year of bottoming-out commodity prices on milk and cheese. The U.S. also lost, on appeal, a challenge to Canada's dairy program before an international arbitration board that would've opened up a new market for Minnesota dairy manufacturers and farmers.

Last month, a dispute settlement panel under the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), the replacement to NAFTA, ruled 2 to 1 in favor of Canada's milk program, which curtails imports through a tariff quota system and is largely viewed as protectionist.

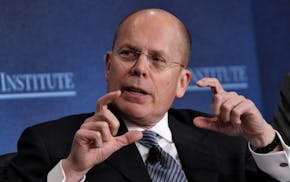

"It's a market that should be there, but it isn't," said Alan Bjerga, a spokesman for the National Milk Producers Federation, which represents many of the nation's dairy cooperatives. "It's safe to say U.S. dairy producers did not get the quota that they thought they were promised under USMCA."

The news wasn't all dour for dairy. The downward trend in fluid milk consumption over the last year was outpaced by faster declines in dairy alternatives such as oat milk. Meanwhile, before leaving for the holidays, the U.S. House of Representatives passed a bill to return whole milk to American schools.

UnitedHealth shareholders give tepid support to $60M in stock-based pay for new CEO

Target recalls more employee groups to downtown Minneapolis headquarters

Ronzoni pasta-maker coming to Lakeville in $880 million Post acquisition

$200M acquisition by Minneapolis company will help it aid other firms make deals