What's the story behind Duluth's Aerial Lift Bridge?

Listen and subscribe to our podcast: Apple Podcasts | Spotify

DULUTH — Duluth's Aerial Lift Bridge is a fitting symbol for a city built on the steel industry.

The massive mechanical steel structure has provided a shortcut to Duluth Harbor for more than a century, allowing shipments of iron ore to reach steel mills around the country. Its distinct shape is a favorite backdrop for local photographers, and has been emblazoned on key chains, T-shirts, wall hangings and many other souvenirs of Duluth.

Its moving deck has inspired its own colloquialism. Locals know they've been "bridged" when nearby traffic is stopped by a ship or sailboat passing under the bridge. (It's perfectly acceptable to briefly abandon one's vehicle for a closer look.)

A few readers have wondered about the bridge's origin story. One reader's great-grandparents owned a few cows on the Minnesota Point peninsula before the bridge was built there. Another former Duluthian remembered enjoying the bridge and ships passing beneath it when she was a child. They turned to Curious Minnesota, the Star Tribune's reader-generated reporting project, for the story of this unique structure.

The short history is that the need for the bridge arose in the 1870s after Duluthians dredged a channel into the Minnesota Point peninsula to improve access between Lake Superior and Duluth's port. That canal spurred the growth of the city's commercial and industrial shipping industry, but turned Minnesota Point into an island. The bridge reconnected the popular peninsula with the rest of the city.

Carving a canal

A natural sandbar known as Minnesota Point or Park Point extends 7 miles from the Duluth neighborhood now known as Canal Park. Wisconsin has its own adjacent 3-mile sandbar, known as Wisconsin Point. Historically, vessels trying to reach the Duluth-Superior Harbor from Lake Superior had to travel through Superior Entry — a break between the two sandbars.

This was good for Superior, according to Duluth historian Tony Dierckins. "[T]he Superior Entry kept the majority of fledgling [shipping] industry on the Wisconsin side of the bay," he wrote in his book, "Crossing the Canal: An Illustrated History of Duluth's Aerial Bridge."

Duluth secured a major railroad terminus and the commerce that came with it in 1870. City leaders were determined to bring more business to Duluth's port

Cue the dredger.

Duluthians carved a waterway through Minnesota Point in 1871, creating a better route to Duluth's port. The shipping canal cut off access to the popular Park Point summer recreation area — and residents and beach aficionados needed a way to travel to and from the mainland. For years, they relied on ferries and rowboats.

A seasonal suspension bridge, removed during shipping season, provided a more daunting solution. Two 60-foot wooden towers and steel cables supported a 6-foot-wide wooden deck, according to a 1904 Duluth News-Tribune article.

"Many stories of hair breadth escapes from a plunge into the canal are told by those who took this perilous trip of 250 feet from tower to tower while the 'bridge,' like a carpet, was flapped in the wind," the paper wrote about the rickety bridge, which lasted from 1879 to 1882.

The people of Minnesota Point needed something more permanent.

The bridge is born

City officials considered and discarded several solutions for spanning the canal — including a tunnel beneath it. Inspiration ultimately came from Europe. City Engineer Thomas McGilvray worked with Minneapolis-based C.A.P. Turner to create a design similar to a transport bridge in Rouen, France.

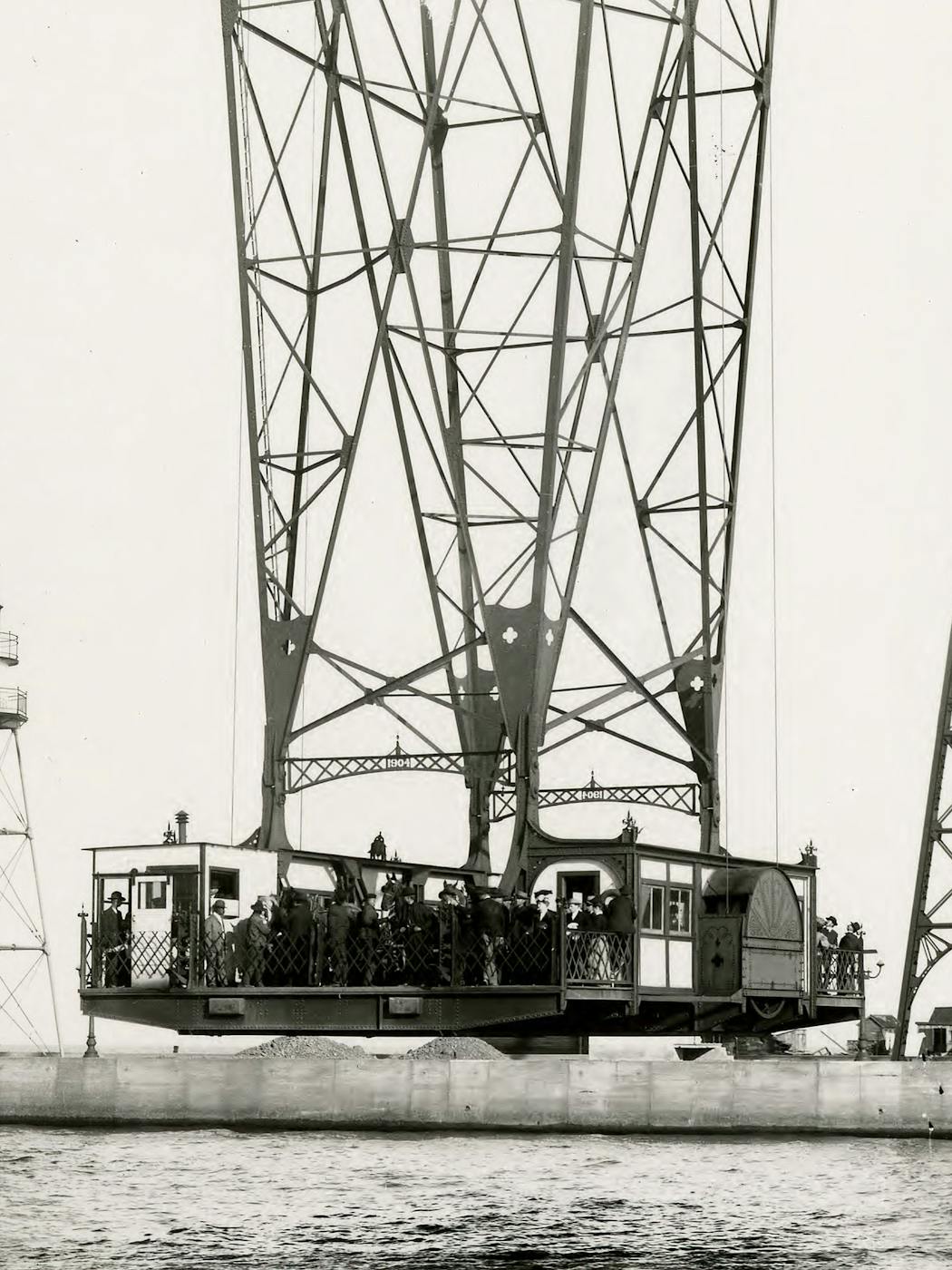

The bridge was completed in 1905. It featured large steel towers on either side of the canal, connected by a steel truss. The structure did not have a moving deck like it does today, however. Instead, a gondola hanging from the truss eked across the water gap at about 4 miles per hour.

The truss was 135 feet over Lake Superior, a height dictated by the Lake Carriers' Association.

McGilvray would later say that the bridge was designed to withstand wide temperature variations — from minus 40 degrees to 100 degrees Fahrenheit. The structure was also capable of withstanding the mightiest of winds, he said.

"Car operates as well when wind blows 60 miles per hour as when no wind is blowing," McGilvray wrote in his book "Duluth Aerial Ferry Bridge," published in the early 1900s.

Before the bridge opened, a crew of local dignitaries took a ride in the gondola. Workers manning the ride had planned some shenanigans for the passengers. One stopped the gondola midway across the canal and whacked a board across the mechanics, causing riders to duck.

"A second journey across and back was made without a hitch and the car drew up to the approach and locked automatically with scarcely a perceptible jolt against the steel springs with form a cushion," according to an account in the Duluth Herald.

Adding the 'lift'

By the 1920s, the gondola concept had outlived its usefulness. It had frequent breakdowns and couldn't shuttle people and cars fast enough. The concept needed modernization.

The idea of a vertical lift bridge with a moving deck had been raised during the initial bridge discussion decades earlier. In the mid-1920s, the island's residents hired a Chicago firm familiar with the lift bridge style to design a new bridge, using as much of the original structure as possible.

Swapping out the old for the new meant expanding the sides of the bridge by 41 feet and reinstalling the truss to the new height. A small house was added to the center of the structure, where a human operated the bridge's movements. A system of counterweights allowed the deck to rise and lower, depending on traffic on land and water.

City officials announced in early January 1930 that it had cost more to run a ferry service between Lake Avenue and Park Point while the new bridge construction was underway ($110,000) than it had to build the original bridge ($108,000).

Five thousand people attended a lowering of the bridge span in the days before it opened to automobiles, according to an account of the event in the Duluth News-Tribune.

"While the span was being lowered the steel workers were jubilant, several calling out for a bottle with which to christen the span and others were content with ... shouting," the paper reported in 1930.

McGilvray didn't have high hopes for the future of "that up and down gadget." In a 1956 interview with the Duluth Herald, the former city engineer predicted that the relatively new bridge wouldn't last forever.

"The removal of this historic landmark, he said with the burr of Scotland still in his voice, is inevitable," the paper reported. The story's headline: "City's famed bridge is doomed."

The bridge earned a spot on the National Registry of Historic Places in 1973, described in its nomination as "the unofficial symbol for the City of Duluth, representing its position as the world's largest freshwater port." It has remained largely unchanged since the 1930 overhaul.

If you'd like to submit a Curious Minnesota question, fill out the form below:

Read more Curious Minnesota stories:

Why was I-94 built through St. Paul's Rondo neighborhood?

Why does Minneapolis keep planting trees under power lines?

Why are vehicle tabs more expensive in Minnesota than in other states?

Minneapolis plows its alleyways. Why doesn't St. Paul?

Why is Minnesota the only mainland state with an abundance of wolves?

Why is Minnesota more liberal than its neighboring states?