Why did Duluth's economy collapse in the 1980s?

Listen and subscribe to our podcast: Apple Podcasts | Spotify

DULUTH — Immense wealth from iron mining and timber fueled the Gilded Age prosperity of Duluth, which was once predicted to become the next Chicago.

Even after logging dissipated in the early 20th century, manufacturing and transporting steel drove the Rust Belt port city's growth to a population of 107,000 by 1960.

But in the early 1980s, Duluth ranked among the 10 most economically distressed cities in the country. By 1983, unemployment averaged 13.2%, a high school had closed and 14,000 people had moved away. The sour mood was crystallized in a billboard that jokingly asked "will the last one leaving Duluth please turn out the light."

Chris Cope, a listener of the Curious Minnesota podcast, sought answers from the Star Tribune's community-driven reporting project about what went wrong.

"When you look at what remains of its past, and consider all the resources it had and still has, you start to wonder why Duluth isn't a bigger deal," he wrote. "What happened?"

The short answer is this: Duluth's three largest employers left town, taking with them more than 5,000 jobs over the course of little more than a decade. The city's economy was particularly tied to the prosperity of northeastern Minnesota mining — and demand for steel plummeted in the 1960s and 1970s.

Closure of U.S. Steel plant causes 'ripple effect'

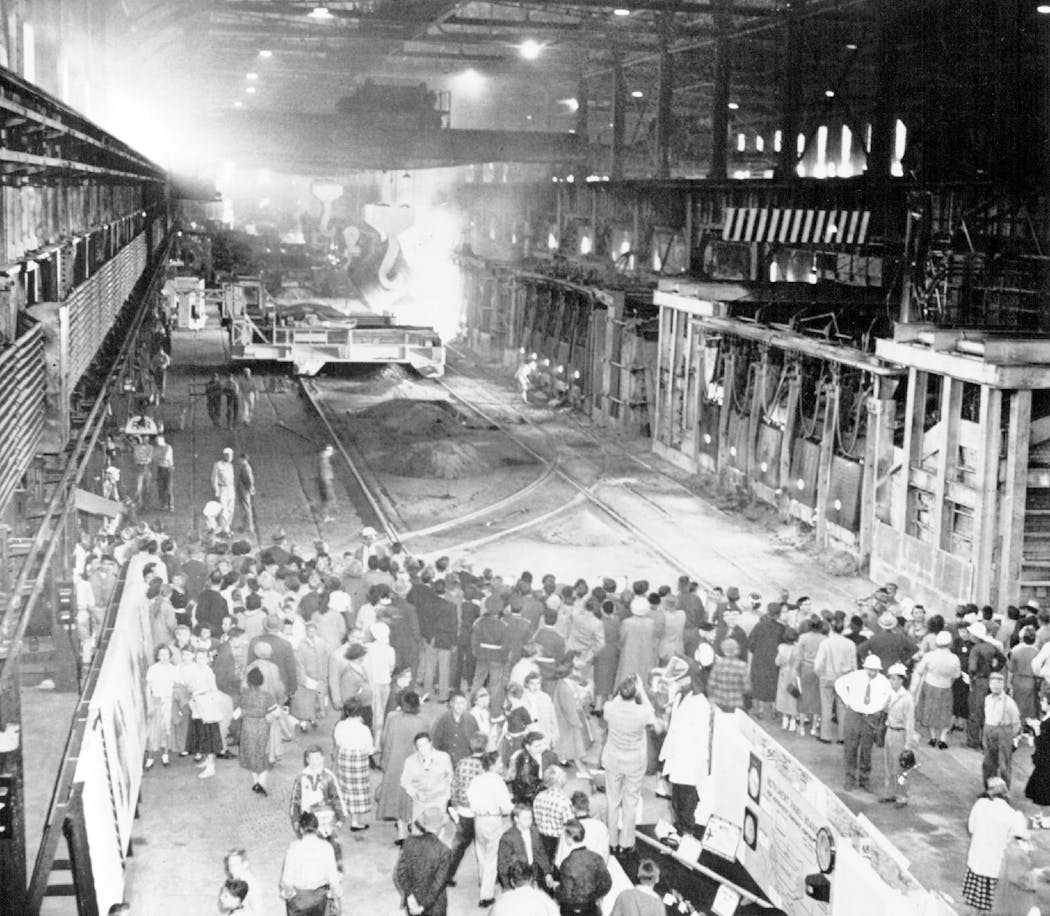

The massive U.S. Steel Duluth Works plant was one of the biggest job centers in Duluth for decades, located in the far western neighborhood of Morgan Park on the banks of the St. Louis River. It made wire products and unfinished steel billets, which were heavily used during World War II and postwar rebuilding efforts.

U.S. Steel began shutting down pieces of the complex in 1971, starting with the closure of its melting or "hot" side — an area that included a coke plant and all of the blast and open-hearth furnaces. With that, 2,500 highly skilled jobs disappeared. The subsequent closures of other sections of the plant in 1973 and 1979 meant several hundred more layoffs. Many departing workers had been there for decades.

The Duluth mill opened in 1915 with the hope that its proximity to the Iron Range would transform Duluth into a major port city, according to a 1971 Minneapolis Star article. The dream didn't materialize, and U.S. Steel devoted more attention elsewhere.

"The mill has never been a great moneymaker," a U.S. Steel spokesman told the paper. When steel was too plentiful, Duluth Works was among the first operations affected.

Duluth Mayor Ben Boo, who had once worked for the plant, called the first closure "a severe blow to the morale of the whole community" in a 1972 Duluth News-Tribune story.

Retired St. Louis County Attorney Mark Rubin was among a group of Morgan Park High School students that lobbied legislators to save the Morgan Park plant.

"We knew how important the jobs were," he said in a recent interview, noting that most everyone knew someone who had worked there or still did. "And the ripple effect was horrible," as fears about shop and school closures were realized.

Local historian Sammy Maida's father worked at the steel plant. When it closed, Maida said, his church lost half its members.

"They transferred to Gary [Indiana], or they went up to the Iron Range or they went on a boat," he said. The closure was "a gut punch."

The company's role as a severe polluter also played into its decision to pull out.

Minnesota Pollution Control Agency Executive Director Peter Gove told the Minneapolis Star in 1975 that the plant violated air quality standards and emitted raw sewage, 5,000 pounds of ammonia and 800 pounds of cyanide into the St. Louis River every day.

Complying with standards was expensive, and U.S. Steel opted to close instead.

And then things got worse.

In 1981, plans for a $400 million coal liquefaction plant on the former U.S. Steel site were dropped. It had been touted as the biggest thing to boost the city in a century.

This was followed in 1982 by the closure of the city's largest employer, a plant operated by frozen-food mogul Jeno Paulucci. Paulucci's decision to move the operation to Ohio, which he attributed to transportation costs, left 1,200 Duluth-based workers unemployed.

The U.S. Air Force then closed its Duluth base in 1983, cutting nearly 1,400 jobs.

Politicians in Minnesota and in Washington, D.C., tried to keep the base open, said retired Duluth News Tribune opinion writer and columnist Jim Heffernan.

"But all the king's horses and all the king's men couldn't save that air base," he said. It had been in decline for years, according to newspaper accounts.

And while a federal prison replaced it, Heffernan said "it wasn't anywhere near the economic impact on the community."

'A changed community'

Duluth's population never recovered from the downturn, but the city has fought successfully to transform its economy.

John Fedo took office as mayor in 1980 at age 29. It was clear Duluth needed to diversify, he said in a recent interview.

He and Robert Beaudin, who preceded Fedo as mayor, pinned their hopes on health care, education, transportation, aviation and tourism — lessening the city's dependence on iron ore and steel.

"We lost a lot of earning power ... and our ability to make that up didn't happen overnight," Fedo said.

The city won several political battles in its efforts to help improve the economy, even as downtown lost department stores and shops to the mall area in the 1980s. Chief among the victories was the interstate that now carves through downtown.

City leaders waged a lengthy fight in the 1980s to extend Interstate 35 with federal money through downtown, supplying funds for bricked streets and a skyway system. The ability to make those improvements was key to revitalization, Fedo said, along with connecting people to the waterfront.

But even if people managed to get past the abandoned warehouses and junkyards filled with cars and appliances in Canal Park, there was no beach.

The city, Paulucci's son Mick and current Grandma's Restaurant owner Andy Borg Jr. spearheaded efforts to create new Lake Superior access, the Lakewalk and a juggernaut tourism hub.

In the late '80s, Lake Superior Paper Industries was built for nearly $400 million, creating 300 jobs. It was the largest investment in the city since U.S. Steel opened the Duluth plant. This was followed in 1990 by the opening of a new convention center, attached to the Duluth Arena Auditorium.

By the early '90s, Duluth had nearly 3,000 more people on its payrolls than the previous peak in 1979, according to a Star Tribune article.

While population has been stubbornly flat for years at just under 87,000, the shopworn city of the '80s is now known for outdoor recreation, aviation, craft beer and a growing medical district. And the port, with its shipping and burgeoning cruise industries, continues to be a major part of city commerce.

"It's true we are not the economic hub for the steel industry we once were," Mayor Emily Larson wrote to Rolling Stone magazine in 2018 in response to a negative article about Duluth.

"Simply put — we are America, where changing industry means innovation," she said. "We are proud of who we are."

If you'd like to submit a Curious Minnesota question, fill out the form below:

Read more Curious Minnesota stories:

Is Duluth the most inland seaport in North America?

If Duluth is such a great outdoors city, where are all the bike lanes?

Was Duluth once home to more millionaires per capita than any other U.S. city?

How much flour would it take to turn Lake Superior into bread?

How important was the Iron Range to winning World War II?

How lumberjacks harnessed an 'ocean of pine' to build Minnesota