Opinion editor's note: Editorials represent the opinions of the Star Tribune Editorial Board, which operates independently from the newsroom.

•••

Walt Myers of Lakeville lost his wife, Sue, to breast cancer in 2019. Exhausted from planning a funeral and shepherding his family through this devastating loss, Myers soon found another challenge on his hands: the near-constant arrival of complex "explanation of benefits" mailings, and then, bills to cover his wife's hospice care.

Myers was prepared to handle his insurance policy's annual deductible, which would have amounted to $4,000. He wasn't prepared for owing about $135,000, an amount he was held responsible for because his wife's hospice was out of network despite assurances Myers had received.

When the envelope would arrive from the insurer, "I would be afraid to open it. I would get this thing in the pit of my stomach that just sat there. Eventually I figured out that it's not gonna open itself. And, then there's another five-figures added on to the total," Myers told an editorial writer this week.

Myers was 66 at the time and faced with years of daunting payments. But with help from his employer and legal advocates, the debt was lifted. The emotion in Myers' voice was clear as he described this as "life-changing."

Fortunately, other grieving spouses won't have to endure what Myers did, thanks to Minnesota legislators and energetic advocacy by Attorney General Keith Ellison. Earlier this year, lawmakers passed the landmark Minnesota Debt Fairness Act, which puts in place significant new safeguards to help consumer struggling with medical debt.

Among the reforms: Spouses will no longer automatically be liable for their partner's medical debt. It's a welcome change. In general, survivors aren't responsible for their deceased partner's debt, according to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. But unlike many other states, Minnesota has long made an exception for sums owed for medical care.

While the Star Tribune Editorial Board is concerned that health care systems already facing bottom-line pressures will have to absorb the amounts owed (and it's not clear how much that will be statewide), medical debt shouldn't be treated differently when a spouse dies. Minnesotans like Myers should be able to grieve without battling major medical bills incurred due to coverage loopholes found deep in an insurance policy's fine print.

Another key change in the Debt Fairness Act will protect patients who get behind on their bills but need ongoing medical care. That's a sensible response to a 2023 New York Times article spotlighting a dubious Allina Health System policy that suspended nonemergency care for some indebted patients.

Allina permanently ended this policy about a year ago, a move the Editorial Board applauded. The new Debt Fairness Act bans the practice for all.

While patients do need to pay for their care and make payment arrangements if they aren't able to, it's important to note that Minnesota relies on nonprofit health care systems. Being a nonprofit confers preferential tax treatment, a privilege that comes with the expectation of providing a community benefit.

That should include a higher standard for working with patients who get behind on their bills. It's difficult to see how cutting off care to someone who has a serious chronic illness and needs ongoing doctor's care fits into a nonprofit health care system's mission. If these nonprofits boards' won't police policies like this, a law like the Debt Fairness Act is a reasonable solution.

Other sensible reforms in the new law:

• Creating new income-based wage garnishments, "ranging from 10% to 25%, rather than the flat 25% garnishment cap that previously existed," according to Ellison's office. Wage garnishment protections will also now cover independent contractors.

• Establishing a new process to help people fight billing errors.

• Prohibiting medical debt from affecting a patient's credit score.

Ellison, as well as state Sen. Liz Boldon, DFL-Rochester, and state Rep. Liz Reyer, DFL-Eagan, merit commendation for their work in passing these timely reforms. Nationally, about 6% of adults in the U.S. owe over $1,000 in medical debt, according to KFF, a nonprofit health care policy organization. About 1% of adults owe medical debt of more than $10,000.

Regrettably, these compassionate debt protections only treat the symptoms, not the root cause, of a health care system whose costs are increasingly unaffordable. Still, these measures will be helpful to Minnesota patients as reforms for broader cost containment are weighed.

One other concern: The new medical debt reforms don't require another key part of the health care system — health insurers — to be part of the solution. That's an oversight when high-deductible health plans are often an important reason why consumers struggle with medical debt. Is there a role, for example, in insurers shouldering some of the responsibility for collecting medical debt vs. leaving this to hospitals and clinics?

Congress needs to consider solutions as well. Unlike other forms of consumer debt, medical debt generally isn't something that you choose to take on. It's for care that's required to save a life or sustain good health. Some patients may not be able to work. Compassion and flexibility are in order, and the new Minnesota law helps ensure that patients will be met with both as bills pile up.

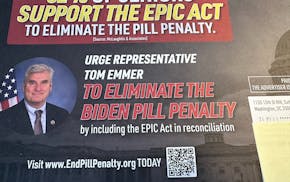

Burcum: About that so-called 'pill penalty'