Who was Hennepin and why did Minnesota name so many things after him?

Listen and subscribe to our podcast: Via Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Stitcher

Many downtown Minneapolis streets derive their names from Frenchmen known for their travels in the Upper Midwest: Marquette, La Salle, Nicollet. But one European traveler stands above the rest in Twin Cities geography: Father Louis Hennepin.

Minnesota's most populous county is named after this 17th century Catholic priest, as is one of Minneapolis' most prominent avenues. Hospitals, libraries, courthouses, churches and parks all bear his name.

That prompted a question that Ron Lundquist of Golden Valley posed to Curious Minnesota, the Star Tribune's reader-powered reporting project: What did Father Hennepin do to make us want to name a county and avenue after him?

"Even though I grew up in Hennepin County, I don't have knowledge about what separated him out and made him special to the extent that we would want to honor him," Lundquist said.

The short answer: Father Hennepin was the first person to put the area that became Minnesota on the map for Europeans — before other exploration of the region.

His documentation of St. Anthony Falls in particular made him a celebrated figure locally, due to the importance of the falls in Minneapolis' origin story.

Hennepin had a zeal for converting souls, a hankering for adventure and the instincts of a publicity hound — though as an explorer, he was perhaps not in the same league as Jacques Marquette, Sieur de La Salle and Joseph Nicollet.

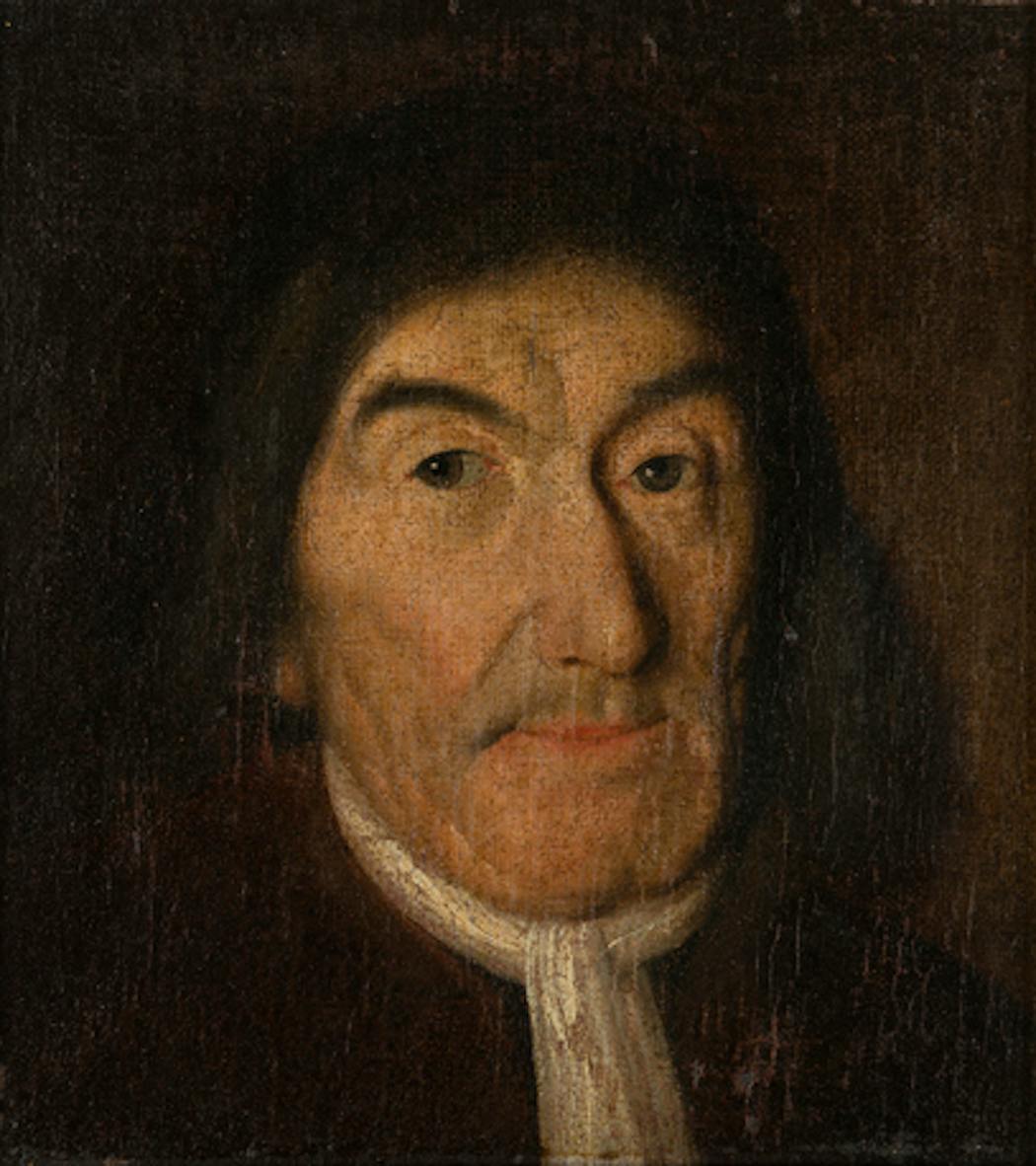

Born in Belgium in 1640, Hennepin entered the Franciscan order in France when he was 20. Full of curiosity about the so-called New World, he found the stories of missionaries inspiring and got his chance to cross the ocean in 1675, when his superiors put him on a ship bound for Quebec.

For the next three years the gritty young friar — dressed in a coarse gray robe cinched with a rope and topped with a cowl — traveled on foot, by canoe and dog sled to visit hunting camps and Indian villages in Canada, preaching the Gospel. Along the way he visited Niagara Falls, becoming the first white man since Champlain to see and later write about them.

Scouting the Mississippi

Hennepin joined an expedition in the late 1670s led by La Salle, who was exploring the Mississippi Valley on behalf of France. After traveling down the Illinois River, La Salle sent Hennepin and two Frenchmen up the Mississippi to scout the area to the north.

Instead, they were captured by a Dakota war party — it's not clear if they were really prisoners or just objects of curiosity — and taken by canoe to the future site of St. Paul. From there, the group set out on a five-day hike to the band's camp on Lake Mille Lacs.

The book "Mni Sota Makoce," a 2012 history of the Dakota people, says that Hennepin's account of these events indicates the Dakota were focused on his "European technology."

"Rather than treating him like an enemy, they attended to him with great honor in hopes that he could provide them with his new knowledge and equipment," the book states.

After a few weeks, Hennepin and another member of the group were allowed to go back to fetch supplies that La Salle had promised to leave them.

It was on that journey, in July 1680, that Hennepin became the first European to set eyes on the only falls on the Mississippi River. He named them "les chutes de Saint-Antoine" — St. Anthony Falls — and fixed them at 50 to 60 feet, probably three times higher than they actually were.

"In his 'great white man' sort of way, he said, 'I must name these falls for my patron saint,'" said John Crippen, executive director of the Hennepin History Museum in south Minneapolis. "It stuck because he went back to Europe and wrote a book about his travels."

St. Anthony Falls supplanted the names that Indians had been using for the cataract. Many Dakota called it Owamniyomni, or swirling water. The Ojibwe called it Kakabika, or severed rock. It would have been news to them that Hennepin had discovered the falls.

The Dakota ultimately released Hennepin and his companions after the intervention of another character who has since become a part of Minnesota history — Daniel Greysolon, better known as Sieur Du Luth. They canoed back down the Mississippi and followed a water route taking them to the Great Lakes. It was the last time Hennepin set foot in Minnesota.

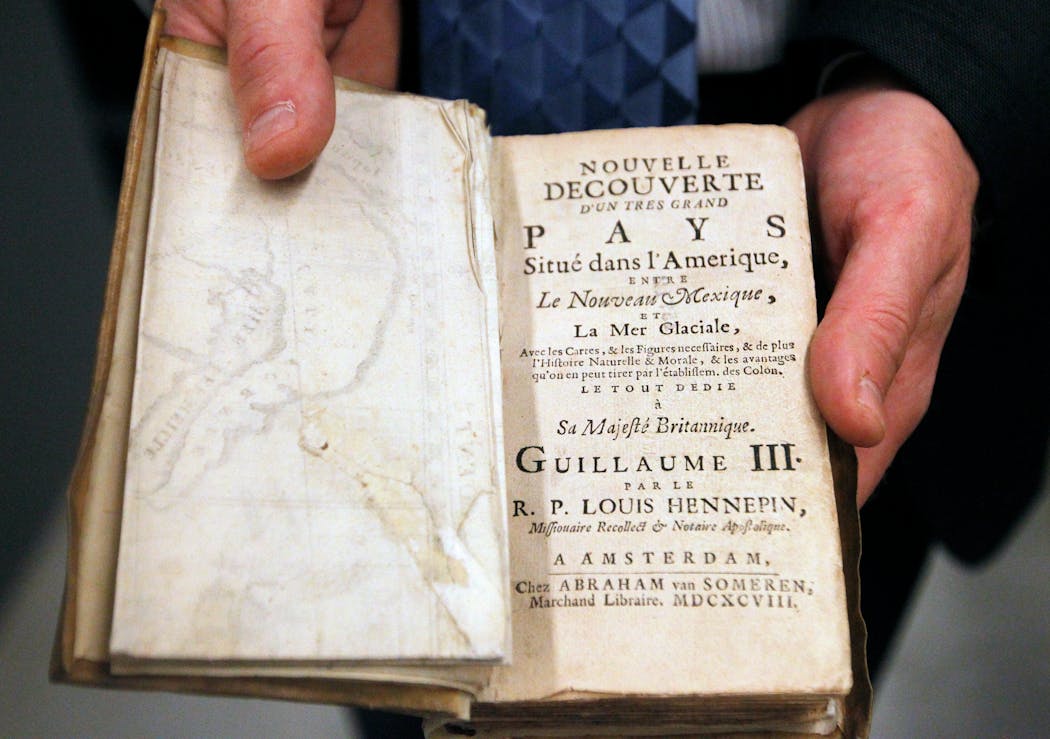

He returned to Europe in 1681, where he wrote "A Description of Louisiana," a book about his travels in the Mississippi Valley. It gave Europeans their first glimpse of Minnesota, as Hennepin recounted his adventures along the Mississippi and with the Dakota people.

"It was one of the 'best sellers' of its day, and Father Hennepin may be considered Minnesota's first 'booster' and publicity man as well as its first historian," the Belgian ambassador to the United States wrote in a 1930 speech delivered on the 250th anniversary of Hennepin reaching the falls.

While his writings made him famous, Hennepin's claims to glory grew more outlandish with each subsequent book. He gave himself credit for discovering the mouth of the Mississippi River, using descriptions that historians say were lifted from other missionaries to bolster his case. He lost all credibility when he claimed to have canoed down the Mississippi from the site of St. Louis to the Gulf of Mexico and back in just seven weeks.

Hennepin swiftly went from highly celebrated explorer to something of a crank. As his reputation for truthfulness plummeted, his enemies list just got longer.

"He speaks more in keeping with what he wishes than with what he knows," La Salle told colleagues. The friar died in obscurity, likely in a Roman monastery, in the early 1700s.

Naming the county

Fast forward about a century and a half. It's 1852 and the Minnesota Territorial Council is busy naming new counties. Farmer and merchant John Stevens, who lives near the falls, proposes naming the surrounding county after Col. Josiah Snelling, builder and first commander of Fort Snelling.

Wrong, says fur trader Martin McLeod, the county should be named Hennepin. The council concurred.

"There's no record that I can see on a debate about that," Crippen said. "To me the interesting dynamic is, what's the most important feature or place in this new county? St. Anthony Falls became the only reason for Minneapolis. I think McLeod had it right. St. Anthony Falls is more important to the county than Fort Snelling."

Snelling had something of a mixed reputation as a good commander who could also be at times an ill-tempered drunk, said Bill Convery, director of research at the Minnesota Historical Society. Hennepin, on the other hand, was a missionary who spread the faith. And most importantly, he had told the world about the falls — which fueled the sawmills that built the city and the flour mills that made it rich.

"He recognized the importance of the falls and promoted them," Convery said. "This was the registration of the state of Minnesota on the pages of history. That's what they were celebrating by naming the county after Hennepin."

Hennepin's name now appears across the Upper Midwest and even New York. There's Father Hennepin State Park on Lake Mille Lacs, where he went in 1680, and Champlin holds its Father Hennepin Festival on the Mississippi every summer. Ronald Reagan grew up on Hennepin Avenue in Dixon, Ill., and a popular Belgian-style saison brewed in Cooperstown, N.Y., is named for Hennepin.

But nowhere is the name more prominent than in the heart of the Twin Cities. Today, the name Hennepin is associated with healing people, borrowing books, holding trials and collecting taxes. Scores of businesses have adopted the name, often in conjunction with the avenue.

And all because an itinerant Belgian priest stopped here briefly to take note of this landmark in the wilderness, as historian Lucile Kane called it.

"For better or for worse," Convery said, "everything that happened afterwards happened because Hennepin made some noise about the falls."

If you'd like to submit a Curious Minnesota question, fill out the form below:

Read more Curious Minnesota stories:

Why does the Stone Arch Bridge cross the river at such an odd angle?

How did early settlers survive their first Minnesota winters?

Does Minn. or some other state have the best claim to Paul Bunyan?

Why did Minneapolis tear down its biggest train station?

How did Dinkytown in Minneapolis get its name?

Did political shenanigans derail an effort to move Minnesota's capital from St. Paul?