Natural food co-ops are known for their organic produce and fair-trade coffee. Their chutes of bulk grains and jars of hard-to-find spices. Their wide assortment of cage-free, farm-fresh eggs and nut grinders that let you crush your own container of almond butter gooeyness.

But what many consumers don't usually associate with today's co-ops are low prices.

Changing values and economic pressures, though, have pushed natural food co-ops to focus more on affordability. This year, natural food co-ops have seen elevated sales as they have dramatically increased cheaper organic offerings such as United Natural Foods Inc. (UNFI)'s Field Day brand. Co-ops have also recently begun to add less expensive, conventional and sometimes even less healthy items including Coke products.

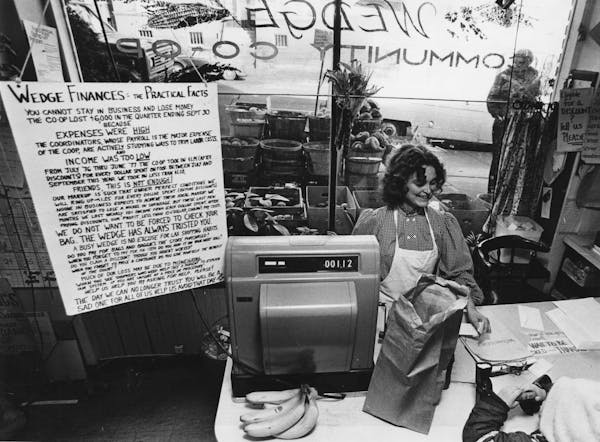

The changes signal an evolution in philosophy from the hippie roots that helped pioneer the Twin Cities co-op movement in the 1970s and went on to sweep the country.

"Co-ops have and continue to struggle over should I stock that product or not," said C.E. Pugh, chief executive of the National Co+op Grocers organization, which is based in St. Paul. "It doesn't really meet my values. It's not local. It's not organic. It's not natural. It's just inexpensive. We are beginning to see co-ops experiment with it."

At the Mississippi Market co-op off 7th Street in the Dayton's Bluff neighborhood of St. Paul, customers can buy a variety of locally sourced and organic food such as air-chilled, free-range hens and farmstead cheese — staples of all three of the Mississippi Markets.

But the E. 7th store, which serves a neighborhood with 19% of residents below the poverty level, also has added 100 items under the discount Essential Everyday private brand, which is owned by SuperValu, now a subsidiary of UNFI, and national brands like Coca-Cola, Sprite and Jif peanut butter found in conventional supermarkets.

"We have observed significant growth in the sales of these products, prompting us to gradually expand the selection across various departments, including grocery, cheese, wellness and produce," said Yani Clement, Mississippi Market's purchasing director, in an email. "Currently our conventional product selection at the East 7th store makes up around 9% of our total product offerings. This expansion not only provides customers with more affordable options but also ensures that we continue to cater to a diverse range of preferences and budgetary needs."

A higher percentage of sales at the E. 7th store also comes from Mississippi Market's "Co-op Basics" line of products, which is a lineup of natural or organic household goods that are priced below the suggested retail price.

Co+op Basics, which National Co+op Grocers started in 2016, was "a game changer" for co-ops because it gave small independent cooperatives the buying power of a larger chain to negotiate lower pricing of organic products, Pugh said. National Co+op Grocers also negotiates Co+op Deals sales flyers.

That negotiating power was essential as more mainstream stores began to offer their own organic private labels.

"Whole Foods has Whole Foods 365, Kroger has Simple Truth, Target has their own organic brand and Walmart has their own private labels," Pugh said. "We didn't have anything like that and we were just getting blown out of the water price-wise."

Now food co-op sales are on the rise thanks in a large part to their increase in cheaper organic goods and conventional grocery products, Pugh said. During the first quarter of this year, sales at the 230 or so co-op stores that are part of the National Co+op Grocers were up 5% compared with last year, boosted by a 30% jump in Field Day sales.

Over the past decade as a whole, the growth was 2% annually, Pugh said.

Since the end of the pandemic, the Wedge Community Co-op has seen store traffic increase with people shopping more frequently.

"We strive to provide options for people," said Rebecca Lee, senior director of purchasing and merchandising at the Wedge. "As we adapt, as all of us adapt to increased prices, we look for more options for people so that they can continue to buy those free-range eggs like they want to but have another option for olive oil that's less expensive."

Buying in bulk is still a major way for people to save money at co-ops. It's 52% less to buy the same oats in bulk as it is packaged, Lee said. Other items that are cheaper in bulk are honey (44%), olive oil (28%) and coffee (20%).

"If you don't need a lot of something, like you are trying a new recipe or if you don't know that you like lentils, you can buy a quarter cup at a time, you don't have to buy a whole package," she said.

Two years ago, the Wedge started its "co-op perks" loyalty program where coupons are sent directly to customers to match their buying habits. The individualized program has proven effective.

David Schmit, 69, of Minneapolis, considers the recently renovated Seward Community Co-op on Franklin Avenue in the Cedar-Riverside part of Minneapolis his family's neighborhood store.

"We like eating healthy and they have an abundance of healthy foods," he said as he pushed a cart of fresh foods like tomatoes and spinach.

However, Schmit said his weekly store visits have become costly as grocery prices at co-ops as well as conventional stores have climbed over the past two years.

"Part of the problem with organics is that they are expensive," Schmit said.

Stetson McAdams, 32, of Minneapolis, visits Seward three to four times a week. His partner works there so their household gets a discount, but even with the savings, it has been hard to cope with the high prices of food at the co-op.

"They are pricier," McAdams said. "It feels like my wallet has shrunk by half."

Natalia Mendez, marketing director for Seward, the oldest co-op in the Twin Cities, said there used to be "very stringent purchasing guidelines" about what merchandise Seward sold.

Seward recently incorporated Jarritos and Mexican Coke to its Franklin Avenue store, additions that have sold well but initially received some pushback about whether those products met Seward's standards. In the end, Seward decided to carry them because "people do want the things that they recognize," Mendez said.

"It's this balancing act," Mendez said

Seward has seen success in adding Essential Everyday and Field Day products, too.

While shopping in bulk or buying generic organic items can save money at co-ops, for many consumers, value is not only about a lower price tag, said Faye Mack, executive director of the Vermont-based Food Co-op Initiative, which helps communities open co-ops.

People want to spend their dollars on what is valuable to them, and they want to support local producers and stores that provide decent wages to workers, she said.

"That piece is often just as important. People are really eager to have control of their access to food," she said.

Ramstad: Readers say Walmart won't be paying the ultimate price of Trump's tariffs

How Minnesota businesses can spot and prevent invoice fraud

No place for cryptocurrency in retirement portfolios

Minnesota Department of Health rescinds health worker layoffs