"Thirty years ago, Black History Month was just a mention on Minnesota Public Radio, and maybe a concert here or there. There wasn't anything sustained here in the Twin Cities."

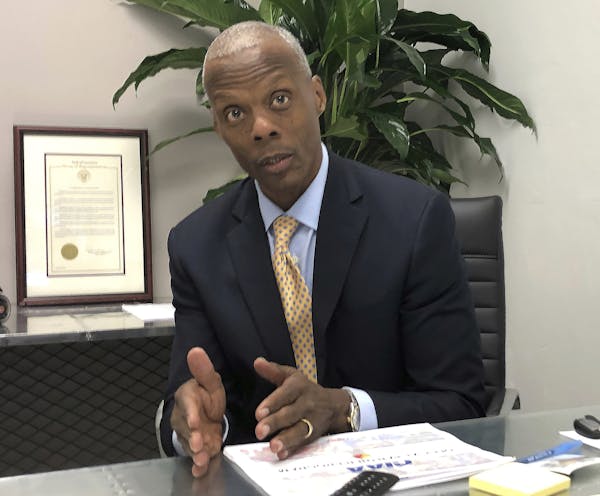

G. Phillip Shoultz III was talking about why VocalEssence founder Philip Brunelle decided to start the choir's "Witness" program three decades ago, and the gaps it was designed to fill in the musical ecosystem.

"The idea was to bring the music of black and African diaspora composers to the concert stage," said Shoultz. "My community, the black community, is celebrating that tradition all year long. Philip wanted to find a way of bringing it to the classical music stage to mainstream audiences."

Those audiences and the singers in VocalEssence were, of course, predominantly white. Was taking music from the African-American tradition and performing it even acceptable? Could it not be viewed as blatant cultural appropriation?

So Brunelle "sought the counsel of some prominent people in the African-American community — Dr. Reatha Clark King at General Mills, for instance," Shoultz said. "The reaction could have been, 'Are you trying to steal our music and take credit for it?' Being wise enough to avoid that was important to make the program be lasting."

"Witness" has lasted 30 years so far, and its achievements will be celebrated Sunday in "Deep Roots," a concert at Orchestra Hall featuring five choirs and a host of guest artists including Billboard gospel chart-topper Jovonta Patton.

But those annual showcase concerts are just the tip of the iceberg. The bulk of the "Witness" program actually happens in local schools.

"We started with just one school, Central High School in St. Paul, sharing workshops and singing with them," Shoultz says, who now runs the program as part of his associate conductor role with VocalEssence. "Now we're in 40 schools annually, and reaching 4,000 students."

Underpinning the outreach to schools is a detailed educational plan that the program makes available to teachers.

"Every year we have a theme, and we convene with our teaching artists to break that theme down into easy lessons that teachers will teach in the classrooms first," Shoultz said. "Then our teaching artists go in and amplify those lessons in a range of workshops, performances and singing activities. And the students create original content under their guidance."

The "teaching artists" employed by the "Witness" program can be singers, photographers, dancers, actors, writers or instrumentalists. They have one thing in common: They are African-American, and can speak authentically about their community's history and experiences.

That, Shoultz says, is a crucial part of what makes the "Witness" program relevant, and sustains it through the eight months of the school year when it operates.

"What I hear from the teachers especially is: 'Thank you for putting artists that look like my students in front of them.' They say the students are really inspired by the idea that maybe they can do something like that someday. For students of color, that is empowering."

But Shoultz emphasizes that students of all backgrounds can benefit from "Witness."

"We work with lots of schools in Apple Valley which have mainly white students," he says. "There's also great appreciation there, because we try to present the truth about African-American people and their culture, not misconceptions."

The culmination of the schools program is a series of young people's concerts at Orchestra Hall, where students see the themes they have been studying represented in performance.

"The most important thing for me is that the students see the artists they've been working with on the concert stage, and they also see VocalEssence," said Shoultz.

It's 'uniquely American music'

At the heart of the program are spirituals, the inspirational choruses sung by African-Americans to lighten the historic load of slavery and social oppression. But the program actively promotes other strands of African-American creativity, and has commissioned 33 new works so far.

A mix of spirituals and newer music will fill the "Deep Roots" program Sunday, with a Community Choir specially formed for the occasion joining the VocalEssence Chorus and Ensemble Singers.

And for those who blanch at the notion of white singers performing music often forged in an adversity beyond their personal experience — only African-Americans really know how to sing spirituals, the argument runs — Shoultz has a sharp response ready.

"That's hogwash," he says. "I take great pride as an African-American singer and conductor in having gone to Germany to learn about the music of Bach, and how to perform it." Teaching non-African-American singers to perform gospel music properly is the same thing in reverse, he says.

"I believe passionately that the music of the African-American community is uniquely American music, some of the first music that was created in this country," he says. "I'm on a mission that everyone should learn this repertoire and sing this repertoire. It belongs to all of us."

Terry Blain is a freelance classical music critic for the Star Tribune.

Streetscapes

Critics' picks: The 12 best things to do and see in the Twin Cities this week

6 new foods worth trying at a Timberwolves game