Aimee Bock's organization was keeping a low profile as it handled millions in government money when the video appeared on Facebook in January.

It purportedly showed one of Bock's employees receiving an astonishing wedding present: an ornamental cart, laden with so much gold that guests gathered around to see it up close.

Abdihakim Nur, a Somali activist and blogger who shot the video, said he heard the gold came from food vendors who were getting rich off the money they collected through Bock's nonprofit, Feeding Our Future.

Nur was appalled, and his video created a stir in the Somali community.

"We cannot close our eyes to such corruption which will put our entire community's name in the news as fraudsters and criminals when we only have a few bad apples," Nur posted.

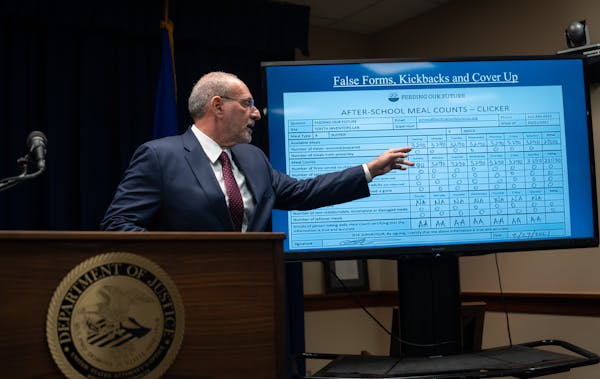

Five days later, the FBI raided Bock's home and a sprawling government investigation went public. Now Bock and her Feeding Our Future co-workers are at the center of a massive criminal probe, accused of collecting more than $5 million in bribes, kickbacks, and other fraud proceeds as part of a wide-reaching conspiracy to defraud public nutrition programs, according to indictments unsealed by federal prosecutors last week. Federal authorities say that tens of millions of dollars aimed for needy children instead bankrolled lavish spending on jewelry, luxury cars and properties in Minnesota and across the globe.

As the accused ringleader of a conspiracy that cost taxpayers $250 million, Bock, 41, is an unlikely criminal mastermind. Though her live-in boyfriend is a convicted felon, Bock's most serious offense is speeding. She has a degree in elementary education and supervised a daycare center for four years.

"I've never even had detention," Bock said in a 2 1⁄2 -hour interview on Jan. 27, a week after the FBI raids. "I am a rule follower ... People are going to believe what they want to believe. But when we're done, they'll see we did the right thing for this community."

Bock is no longer talking to the news media, but she talked expansively about her career and her efforts to expand the government's free meals program into Minnesota's East African community when she still hoped to avoid being criminally charged.

She cried several times during the interview. The first tears came when she talked about the FBI raid on her home. She cried again when she explained how the government froze her bank accounts, making it impossible for Feeding Our Future to continue operating. She also choked up when describing how she and her former husband were forced to file for bankruptcy in 2013 to deal with thousands of dollars of medical bills related to their youngest son.

But Bock was clear-eyed about what she considers her mission in life, which she described as finding a way to help level the field for immigrants and other people of color. She spoke with the fervor of a crusader for human rights trying to leverage government funding to help poor children and their neighborhoods.

"I am the white lady," Bock said in the interview. "It's no secret. I can open the door and I can hold it open and provide the security so it is safe for them to walk through. Because every time they've tried to walk through the door it's gotten slammed in their face."

It was a classic Bock exhibition, like many that have endeared her most visibly to the local Somali community, where she became something of a cult figure long before the January raids.

The recent charges paint a scenario in which Bock was able to capitalize on her unusually strong relations with the Somali community to create a staggeringly successful criminal enterprise, one in which immigrants were willing to spend hundreds of thousands of dollars to gain access to her money-making club.

Even Bock's critics marvel at her ability to connect with immigrants who can sometimes barely speak her language. Omar Jamal, a local Somali activist, said it was stunning to see nearly 300 Somali community members turn out to celebrate in 2021 when Feeding Our Future won a court case against the Minnesota Department of Education that paved the way for the nonprofit's huge growth.

The high point of the evening came when a Somali woman performed a traditional buraanbur to honor Bock, praising her as "a woman who cannot be targeted."

"It was like we have the female version of Robin Hood in Minnesota," Jamal said recently. "There was nothing to be afraid of. She defeated the state ... That is the myth Aimee created in the community."

How Bock got here

Bock grew up in Cottage Grove and moved to Duluth for college, graduating from the University of Minnesota, Duluth in 2003 with an education degree. She obtained her teacher's license but never worked in the profession fulltime, serving briefly as a substitute before having the first of her two sons in 2006.

After moving to the Twin Cities with her family in 2009, Bock got a job at a daycare center in Burnsville, starting out working with infants. She said the job completely transformed her outlook on life and work.

One of the perks of the job, she explained, was discounted daycare for her two toddlers. But Bock said her new colleagues strongly encouraged her to bring the kids to one of the company's other suburban locations, explaining that Bock's sons would be the only white children in Burnsville.

"I don't think I ever cried so hard," Bock said. "It shook me to my core. So I began advocating and working to make sure that our children aren't put on a different path. Everyone says kids [of color] are left behind. They are not left behind. Our system makes strategic decisions to hold them back and I couldn't be a part of that."

In 2013, Bock joined the Minnesota Association for the Education of Young Children, where she helped more than 300 child care centers get the training they needed for accreditation. Many of those centers were owned by Somalis and other immigrants, which made Bock the go-to person for anybody who wanted to tap into that community.

In 2015, that experience led Bock to Providers Choice, an Edina-based nonprofit that bills itself as the "largest sponsor" of government meal programs in the United States. At the time, Providers was eager to sign up new, independent child care centers for the government's meal program. It's also where Bock met Christine Twait, with whom she would later start Feeding Our Future.

"She was the ideal candidate," Twait recalled recently. "There was huge potential."

Within months, however, Twait and Bock became frustrated by the pace of change and chose to leave and start their own nonprofit. Instead of signing up 100 or more centers, as they hoped, just 18 new centers joined Providers Choice in 2015, state records show.

Twait blamed the slow pace on Providers Choice's insistence on documenting eligibility at levels above those required by the government. Providers didn't see the same problem.

"One of the approaches that we had was that we would grow carefully and slowly, enough that we would be able to ensure the success of any center that we brought on," said Gail Birch, founder and former CEO of Providers Choice. "They had a different opinion."

Bock and Twait's new nonprofit, Partners in Nutrition, had a tough start. The group sued the Minnesota Department of Education to win approval, and the two-year battle took a toll on Twait's mental health. She left Partners in 2017, turning over the reins to Bock.

"She loved conflict," Twait said of Bock. "Aimee was absolutely energized by the legal maneuvering. She really thrives on difficult conversations."

Bock's tenure didn't last long. She was fired for misconduct in 2018, according to a complaint Partners filed with federal regulators over Feeding Our Future's conduct in 2019. Through her attorney, Bock declined to address the reasons for her termination.

Partners continued to feud with Feeding Our Future as the new organization made inroads with its provider network, taking over at least 28 meal sites from Partners in 2019, state records show. Partners complained that Feeding Our Future was breaking the rules by initiating contact with its providers, which is forbidden, but state regulators dismissed the complaint in 2020, saying the allegations "could not be substantiated," records show.

Some operators said they were attracted to Feeding Our Future because the group kept just 10 percent of reimbursement claims for administrative fees, versus 15 percent at other nonprofits. Others were drawn by the huge paychecks that were possible.

Jamal said it became a game for some operators, who posted their increasingly large six-figure checks on social media.

"The word got out like fire," Jamal said.

Fardowsa Ali, owner of the Hooyo Child Care Center in Minneapolis, said she signed up with both Partners and later Feeding Our Future because Bock probably kept her center from closing by providing last-minute training just before a state inspection.

"I told everybody in the community, that lady has a heart," Ali said.

Like other center operators, Ali said Bock made sure she got every dollar she was entitled to by flagging problems on her reimbursement claims.

"Other groups promise to do all of the paperwork for you, and then after you sign you have to do all of the paperwork on your own," Ali said. "But Aimee, she made it easy."

According to federal prosecutors, Bock made it too easy for meal providers to cheat the system by approving falsified reimbursement forms listing hundreds of children who didn't exist.

Some members of the Somali community said they became suspicious of the organization in 2021.

"The people who were running the sites had been living in Section 8 housing. Poor people," Nur said. "And all of a sudden they were living in $1 million houses and driving nice cars. It was a free-for-all."

Bock, who set her salary at $190,000 this year, was forced to turn over $185,000 in her bank account and the keys to her 2013 Porsche Panamera during the Jan. 20 search of her home. Authorities also seized $13,462 in cash from her.

During her interview, Bock insisted she didn't steal a penny from the government. But she said it's possible she wound up surrounded by crooks.

"I don't have a criminal mind," Bock said. "Could I be out-smarted by somebody who is good at it? Sure. But I firmly believe that is not the case. I believe this is an attack on the community. I believe this is punishment for going against the grain."

Staff writer Faiza Mahamud contributed to this report.

Want to share info with the Star Tribune? How to do it securely

'Safe recovery sites' would offer syringes, naloxone and more to people using drugs. The plan could be in peril.

New Minnesota GOP leaders seek peace with party's anti-establishment wing

Who is Republican Lisa Demuth, Minnesota's first House speaker of color?