Tracy Wesley stood near his hearse in the parking lot of New Salem Missionary Baptist Church in north Minneapolis, knowing this crisp fall morning would soon turn into a stew of grief and anger.

The day before, Wesley had embalmed then dressed the young body that now lay inside the church. Wesley had slept poorly, which is typical before draining days like these, then read Bible verses over coffee. In his 35 years at Estes Funeral Chapel, where Wesley serves as funeral director and CEO, he has directed thousands of funerals and borne witness to any number of traumas in Minneapolis' Black community. But funerals like today's, for a 12-year-old boy gunned down on his first day of sixth grade, hit hardest.

The family was inside, viewing the boy's body. Security shooed away media. One man out front wore a bullet-resistant vest. Wesley sometimes knows in advance of potential gang violence at funerals, and although that was not the case this morning, he always knows it's possible: A few months before, Wesley was caught in the midst of a fatal shooting moments after a funeral.

Wesley cannot comprehend how we have gotten to this point: We as Minneapolis residents, as Americans, as humans. He's done funerals for Black men whose names have become synonymous with a nationwide movement for police reform, names like Jamar Clark, George Floyd, Daunte Wright. But he's also directed funerals for scores of young people slain in gang-related violence. He hates that even the most tragic of these names — like 6-year-old Aniya Allen or 9-year-old Trinity Ottoson-Smith, both shot and killed earlier this year — tend to be forgotten.

His up-close view of Minneapolis' skyrocketing homicide rate, which is approaching its mid-1990s record, stirs up all sorts of emotions: of lives of deprivation that lead youth toward gangs, of gun culture running rampant on the streets, of broken homes in broken neighborhoods, of the frayed relationship between police and the Black community.

"At what point would a 12-year-old cause such a threat that you would feel the need to just gun him down?" Wesley wondered aloud. "It's so senseless and unnecessary and unwarranted. My anger comes from the why. Why do you continuously do this? Why? Why?"

In the church parking lot, though, there was no time for soul-searching. Wesley had a job to do. Inside the church, one more grieving family was waiting for him.

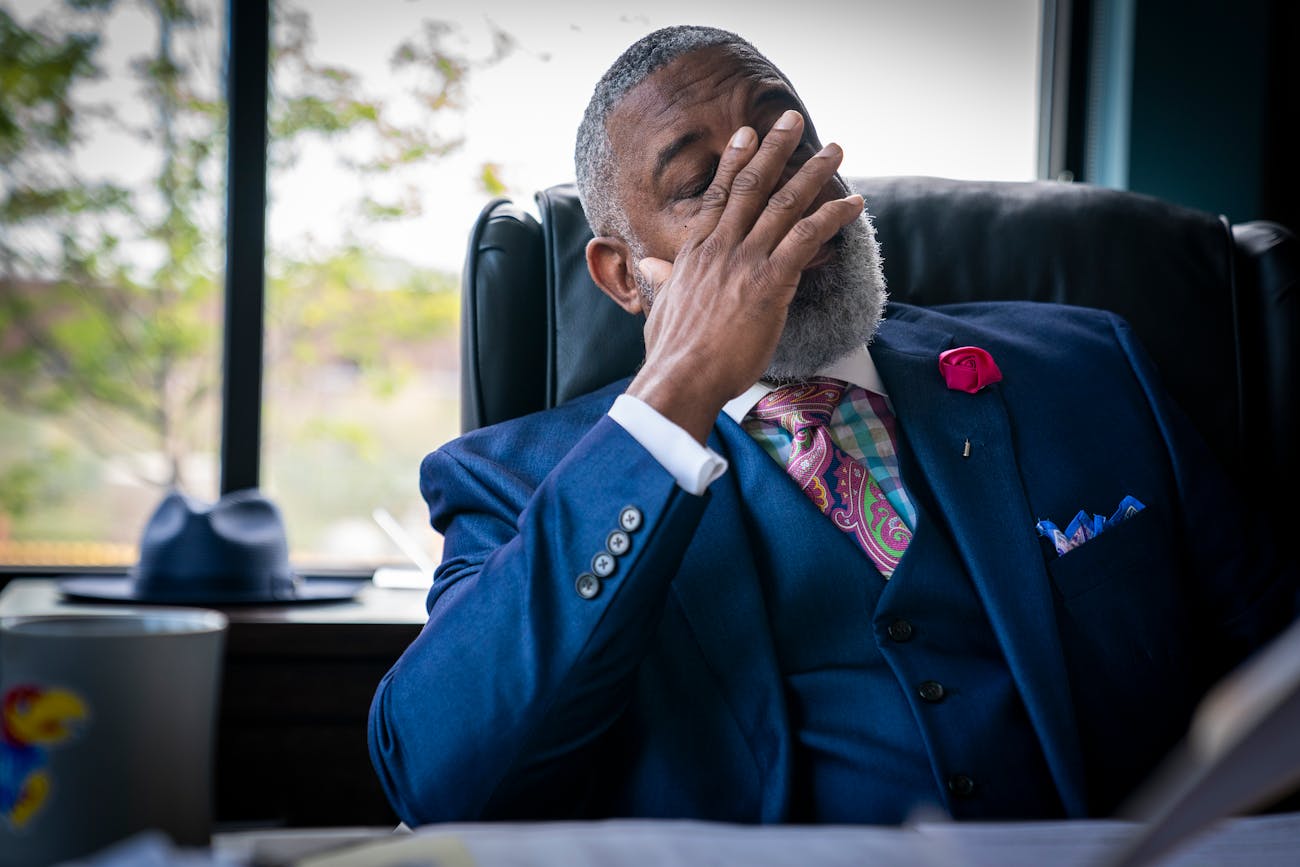

At his funeral home in the heart of Black Minneapolis, Wesley serves as a shepherd of Black grief. The 55-year-old father of two cuts a striking and distinguished figure, showing up to work in an array of three-piece suits and fedoras. His baritone voice is at once booming and reassuring. His graying beard is well-kept, as dignified and soothing as his presence when families walk into his funeral home on a street named after his uncle: Richard Estes Avenue.

Last summer, Wesley found himself thrust into the middle of the most visible moment of Black trauma in a generation.

Wesley put on three funerals for George Floyd: in Minnesota, North Carolina and Texas. In one sense, Wesley was doing what he's done thousands of times since he moved here in 1985 to work for this community pillar his uncle founded 60 years ago. He embalmed the body. He organized services. He tried to lighten the family's pain.

But never before had a funeral taken on this symbolic weight. Rev. Al Sharpton called. Armed security guarded his funeral home once the body was inside. Realizing how volatile the politics had become, Wesley packed his Glock 9-millimeter pistol for the drive to take Floyd's body to North Carolina — until movie mogul Tyler Perry chartered a jet.

"This was something bigger than just a funeral," he said.

Wesley was horrified by the video of Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin killing Floyd. He'd watched previous videos of Black men killed by police — Eric Garner in New York, Walter Scott in South Carolina — but this was different. Maybe the look on Chauvin's face. Maybe the interminable length of Floyd's suffering. Maybe just the proximity. To Wesley, it symbolized a lack of accountability for how police treat Black men.

The movement that picked up steam after Floyd's murder is, Wesley believes, righteous and just. This time, he believes there's momentum to affect real change. Police accountability is a nuanced issue, Wesley said; he's only had respectful interactions with police, and he believes defunding Minneapolis police would hurt the Black community most of all. But he's heard enough stories about police treatment of young Black men to recognize something big needs fixing.

"Nothing much is different," he said. "It's just that people are seeing it."

But there's another problem, too, plaguing his world: Gang-related violence upending his neighborhood. "This is stuff I never thought about doing when I got into this," Wesley said. "It was never to this degree." And Wesley is stumped at the lack of momentum to fix that problem.

Two blocks from Estes Funeral Chapel is the Minneapolis Police Department's Fourth Precinct headquarters surrounded by chain-link fences.

Police in Minneapolis' northwest section, a hub for gang violence in Minneapolis, respond to far more shootings and homicides than in the city's other four precincts. So far in 2021, 35 of the city's 78 homicides occurred here. While nearly half the city's homicides this year have happened in the Fourth Precinct, other parts of the city have been virtually unscathed. The Second Precinct, in northeast Minneapolis, has seen three homicides this year. The Fifth Precinct, in southwest Minneapolis, has seen five.

This comes as Minneapolis creeps closer to a record no one wants broken. In 1995, 97 people were killed during an era that earned the city an ignominious nickname: "Murderapolis."

Wesley remembers those days vividly. He had grown up outside Kansas City, his father the first Black elementary school principal in Olathe, his mother a General Motors factory worker. When his family visited the Twin Cities, they'd stop by his uncle's funeral home. Young Tracy would often disappear. They'd find him in the chapel, staring at bodies laid out for services.

"From when I was 6," he said, "I knew this was what I was supposed to do. You know how ministers say God called upon them to preach? I felt like God said to me, 'You should be in the funeral business.' "

Wesley had been ring bearer in his uncle's wedding in 1972, and his uncle would continue as a commanding presence. Wesley admired his dedication to north Minneapolis. "My husband stayed here when everyone else left," said Estes' widow, April Estes.

Being a funeral director is part art, part science, part pastoral care. Wesley loves embalming — he is the only licensed embalmer at Estes Funeral Chapel — and he believes families appreciate a loved one laid out as lifelike as possible. (Wesley embalmed and dressed his own parents. It felt like therapy, he said, "the very last act of love I can give them.") The core of his calling, though, is a grief minister who gives families a memorable "homegoing" for a loved one.

But it's one thing burying an 80-year-old after a long, fruitful life. Those deaths feel natural, and Wesley knows those funerals can be cathartic celebrations. What's unnatural is lives cut short by senseless violence.

His first jarring moment came shortly after he moved to Minneapolis in the mid-1980s, working for his uncle and living upstairs at the funeral home. Nearby, a man had killed his girlfriend and two children. It was brutal and senseless. Wesley was shaken.

By the mid-1990s, as crack and gang violence wracked north Minneapolis, things became more difficult. A vibrant Black neighborhood — the funeral home was once surrounded by minority-owned businesses like a grocery, pharmacy and chiropractor — got hollowed out. After reports of crack being sold out of a McDonald's drive-through, the fast-food restaurant shuttered. It became an empty lot for two decades.

Funerals for young Black men became far too common. It got so bad that a third of Wesley's funerals one year stemmed from gang violence.

Back then, he believed things would get better. And they did. By 2009, the city had only 19 homicides, a fifth as many as 14 years before.

But these things come in waves, and the latest wave is bad. Today, Wesley's city echoes that scary, dangerous time of a quarter-century ago. In this era, though, Wesley sees gang culture as even more coarse. "A total free-for-all," he called it.

If the defining funeral of Wesley's 2020 was George Floyd's, the defining funeral of Wesley's 2021 was Aniya Allen's.

Late on the evening of May 17, the 6-year-old was eating McDonald's food in her mother's car. A shootout erupted. A bullet struck her in the head, killing her.

The tragedy dominated the news for days. Demonstrations were organized. There was a remembrance in September on what would have been the girl's seventh birthday. But Wesley noted the outpouring of grief and calls for action were nowhere near as intense as after Floyd's murder. And, he noted, Aniya's murder remains unsolved.

The overriding trauma of last year — how a community witnessed a videotaped murder then exploded in rage and sorrow — has shifted to this year's trauma of gang violence engulfing the community Estes Funeral Chapel serves.

The traumas are separate but related, especially for a Twin Cities Black community that can recite a litany of generational inequities. It's not lost on Wesley that these parallel traumas come amid the COVID-19 pandemic that has killed Black Americans at a rate twice that of white Americans. His funeral home has dealt with nearly 100 of these deaths.

What stumps Wesley is how one of these traumas changed the dialogue on race, equity and policing — while the other trauma, despite all these deaths in north Minneapolis, has gone comparatively ignored outside these neighborhoods.

"As much as you've seen from all the police killing these unarmed people, you go to the news every weekend in Chicago and there's 100 people that have been shot!" Wesley said. "We know something needs to happen. But where's the energy around that?"

What Wesley is saying is this: Why did the tragic murder of George Floyd begin a movement, while the tragic murder of Aniya Allen did not?

Weeks after Wesley buried Aniya, he was at north Minneapolis' Shiloh Temple International Ministries for the June funeral of a 24-year-old killed in a shootout at a downtown nightclub. Wesley knew this gang-tinged service could be dangerous. He spoke with police about extra security, and he wore his bullet-resistant vest.

After the funeral, a fight broke out in the church parking lot. Gunfire erupted. One young man was killed.

Nothing like this would have happened in the mid-1990s gang wars, Wesley said. "Just craziness," he would say later. "I just don't know what we're going to do with these young men."

The pastor opted out of the burial at Crystal Lake Cemetery, so Bruce DeArmon, Wesley's assistant funeral director, stepped in. As DeArmon stood by the casket and recited the Lord's Prayer, gunshots again flew. DeArmon hit the ground. He sprained his wrist.

"It makes you go home and hug your kids, your grandkids," DeArmon said. "Little baby caskets — I didn't get into it for that. I always imagined burying 90-year-old people that lived a long life."

For Wesley, funerals like these bring anger on behalf of grieving families: "There doesn't seem to be any closure," he said. "That no-snitching thing. It's almost like it's double-traumatizing, because there's the death, and then no one held accountable for causing it."

Being surrounded by death has given Wesley a deeper appreciation for life itself. Today, just like in the 1990s, Wesley believes things will improve. He has faith they will, even if he doesn't know how.

In the meantime, he wrestles with the why.

"How did we get to this point where life is not precious?" Wesley wondered. "No matter what the circumstance is, how did we get to the point where you just don't care? I don't understand. I don't understand how we've gotten to a point where we don't value someone's life."