Nationwide, people expressed outrage when prosecutors released the preliminary findings of George Floyd's autopsy, highlighting cardiovascular disease and "potential intoxicants" in his system, as if those factors might explain his death as police officers pinned him to the ground.

The findings contained just one mention of physical trauma, noting that Floyd's body showed no signs of asphyxia or strangulation. The public and some medical professionals cried foul, putting Dr. Andrew Baker, Hennepin County's medical examiner, squarely in the hot seat.

But neither Baker nor his office had released those findings. He was still performing Floyd's autopsy at the time. The preliminary findings were summarized by prosecutors in the initial charging documents against former officer Derek Chauvin, the veteran Minneapolis police officer who had pinned his knee onto Floyd's neck for nearly 8 minutes as Floyd begged for air and witnesses pleaded with officers to stop.

The preliminary findings hung over the case for five days before Baker released the full autopsy report. He ruled Floyd's death a homicide, finding that the officers killed him by subduing him, restraining him and compressing his neck.

The way the preliminary results were first presented confused the public and prompted demands for Baker to resign or be fired. Opinion articles, published around the country, demanded that medical examiners have more independence from law enforcement. Two Hennepin County Board members voted against renewing Baker's contract.

Yet some defense attorneys say Baker's been given a bum rap.

"The details that we initially saw were cherry-picked by prosecutors," said Mary Moriarty, Hennepin County's chief public defender. "They were taken out of context of the entire report. But Dr. Baker was doing what a medical examiner does: document absolutely everything they see."

The Hennepin County Medical Examiner's Office is independent. The examiner answers only to the County Board. Moriarty acknowledged, however, that even independent medical examiners or coroners can skew their findings in favor of prosecutors or police officers.

Baker has never been one of those medical examiners, she said.

"He has always been independent and fair-minded," Moriarty said. "We don't always agree, but he certainly is not affiliated with prosecutors or in anyone's pocket."

Baker declined to comment for this article.

The controversy

The earliest findings from the autopsy were released when Hennepin County Attorney Mike Freeman's office filed third-degree murder charges against Chauvin four days after Floyd's death. Prosecutors cited three preliminary autopsy findings: That there were no physical signs Floyd died of asphyxia, that he had cardiovascular disease, and that his health conditions, plus "any potential intoxicants" and the police restraints, likely caused his death.

Floyd's family and their lawyer cried foul. They hired two pathologists who conducted a second autopsy that concluded Floyd died of asphyxia.

A collective statement written on behalf of nearly 20,000 black physicians from around the country called the preliminary findings "misleading," saying they inappropriately raised doubts about Floyd's character and undermined Chauvin's role in his death.

The early findings had little medical relevance to the cause of death, said Dr. Derica Sams, a physician in Chapel Hill, N.C., who helped organize and write the statement. It was meaningless to point out that there were no traumatic signs of asphyxia, Sams explained, because asphyxiation can often occur without leaving behind obvious signs of trauma.

She said it was irresponsible at best for prosecutors to note that Floyd may have had drugs in his system before the toxicology reports were complete. That merely served to present Floyd in a bad light and indicate that other medical problems may have killed him, she said.

The full report

Facing a public outcry, Minnesota Attorney General Keith Ellison took over the prosecution two days before the full autopsy was released. Once it became public, Ellison added more severe second-degree murder charges against Chauvin and charged the other three officers at the scene of the arrest as accomplices.

Baker's autopsy report found that Floyd died when his heart stopped as officers subdued and restrained him by compressing his neck. The report lists heart disease, fentanyl intoxication and recent methamphetamine use as "other significant conditions," indicating that they may have made Floyd's death more likely.

Listing underlying diseases and drug intoxication in an autopsy report is "usual practice" for a medical examiner, Dr. Sally Aiken, president of the National Association of Medical Examiners, said in a statement. "Death is a complex process and often occurs with multiple interacting contributing causes," she wrote.

These kinds of restraint-associated cases are especially complex, said Dr. Judy Melinek, a forensic pathologist in the San Francisco Bay Area with no connection to the Floyd case. Forensic pathologists may disagree over what to include under "other significant conditions," Melinek said. "But it doesn't change the fact that it's a homicide."

Floyd's family paid for a second autopsy conducted by Dr. Michael Baden, a former chief medical examiner of New York City, and Dr. Allecia Wilson of the University of Michigan. While their full report hasn't been released, Baden and Wilson said at a news conference that they determined that Floyd died of asphyxia, caused when the police restraints cut off blood and oxygen to his brain.

Baden disputed Baker's findings of heart disease.

"I wish I had the same coronary arteries that Mr. Floyd had that we saw at the autopsy," he said.

Wilson hedged, however, noting that second autopsies have some limitations, and that they didn't have access to certain parts of organs.

Both Melinek and Aiken said second autopsies typically provide less information overall, because body tissues are altered during the first autopsy or even removed for further analysis. Melinek said she would expect any parts of Floyd's heart that showed disease to be removed and kept by the medical examiner's office.

Freeman's office declined to be interviewed for this story.

On June 11, the Hennepin County Board voted 5-2 to reappoint Baker to another four years as medical examiner. Explaining her no vote, County Board member Angela Conley cited the early findings that "any potential intoxicants" may have contributed to Floyd's death.

" 'Potential' does not necessarily mean that you are certain," Conley said. "So why would we list that?"

Conley said she believed the early findings were the catalyst for what she called the initial, "insufficient" third-degree murder charge against Chauvin.

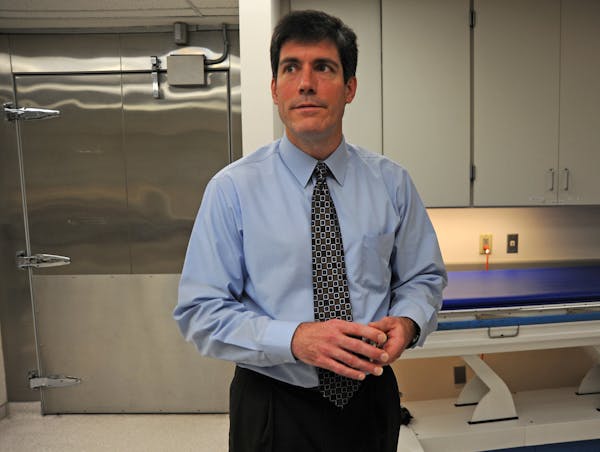

Baker's bio

Baker has been the Hennepin County medical examiner since 2004. He graduated from the University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine and served in the U.S. Air Force. In the late 1990s, he helped the FBI investigate crimes against humanity in Kosovo, providing evidence for an international criminal tribunal.

He was stationed in Washington, not far from the Pentagon, during the Sept. 11 attacks. For several months, he helped identify those who died at the Pentagon and on American Airlines Flight 77.

Baker has often been an expert witness for prosecutors and defense attorneys alike. He is widely respected, said Barry Scheck, a longtime defense attorney in New York who co-founded the Innocence Project. His testimony in 2017 helped exonerate Kirstin Lobato, who had been wrongfully convicted in 2006 and sentenced to up to 45 years in prison. Lobato was represented by lawyers with the Innocence Project.

"If the prosecutors, the public defenders and your colleagues in the medical community all have respect for you, it says a lot," Scheck said. "He is a straight shooter."

Scheck said that by highlighting that there were no physical signs of asphyxiation, prosecutors misled people into believing that Baker had ruled out neck compression as a cause of death, he said.

Scheck said he doesn't see much that separates Baker's official findings with the autopsy conducted at the behest of Floyd's family.

"Now that we've seen the ultimate conclusion, I don't see any material differences for legal purposes between the two autopsies," Scheck said.

Want to share info with the Star Tribune? How to do it securely

'Safe recovery sites' would offer syringes, naloxone and more to people using drugs. The plan could be in peril.

New Minnesota GOP leaders seek peace with party's anti-establishment wing

Who is Republican Lisa Demuth, Minnesota's first House speaker of color?