PHILADELPHIA – The godfather of NCAA tournament projections is courtside, coolly checking the pings on his phone before saddling up for his ESPN broadcast duties.

He has just crafted his first in-season men's basketball bracket projection on this November evening, revealing to his legion of followers which 68 teams he predicts will fight it out for four tickets to Minneapolis in April.

This is serious stuff — "Who's in?!" Who's out?!" — as sports debates go, but Joe Lunardi is stressing more about St. Joseph's vs. Illinois-Chicago.

His laptop is closed and his phone is on mute. "Joey Brackets" right now is Administrator Joe. Lunardi doubles as the St. Joseph's director of marketing for athletics. He bounces between greeting Hawks fans and checking in on several pregame scenes. The gameday production crew includes his youngest daughter, Elizabeth, who transferred from Hofstra last year to be closer to her father.

Lunardi, the man behind bracketology, may seem part machine to sports fans — spitting out projections at high speed for millions to scour and debate. The truth is he is a husband and father of two daughters, a key university official, a media personality, as well as an architect of brackets.

Away from Philadelphia and St. Joseph's, the Lunardi name for nearly two decades has been attached to the process and debate around predicting which teams will form March Madness. Fans and followers anxiously wait for his picks, often with red pens in hand.

"I usually tweet my bracket before the game and don't look at it for two hours," said the 58-year-old Philadelphia native. "Then, I get home and people tell me how much I screwed up."

Before they split for their pregame duties, Lunardi hugs Elizabeth and gives her a package at the scorer's table. It's an Ariana Grande T-shirt he ordered for her, for an upcoming concert.

"Love you, Dad," she says. "Have a good game."

Just Joe

Lunardi's projected field gets updated daily on his laptop, regardless of whether it's posted online. His master Microsoft Excel spreadsheet resembles the tournament selection committee's cheat sheets, complete with the new-for-2019 analytics. Any time Lunardi peels off a fact for a tweet, it spreads across college basketball nation.

Long before Twitter, ESPN knew it had something with Lunardi's first bracket page in 2002. It received hundreds of thousands of hits within an hour. He then made his on-air debut. Lunardi knew his stuff but was clueless how bracket talk would translate to TV, especially from a small production studio in Philadelphia.

"I was just doing whatever they told me in my ear," he said. "I was trying not to blink, pick my nose or look in the wrong direction."

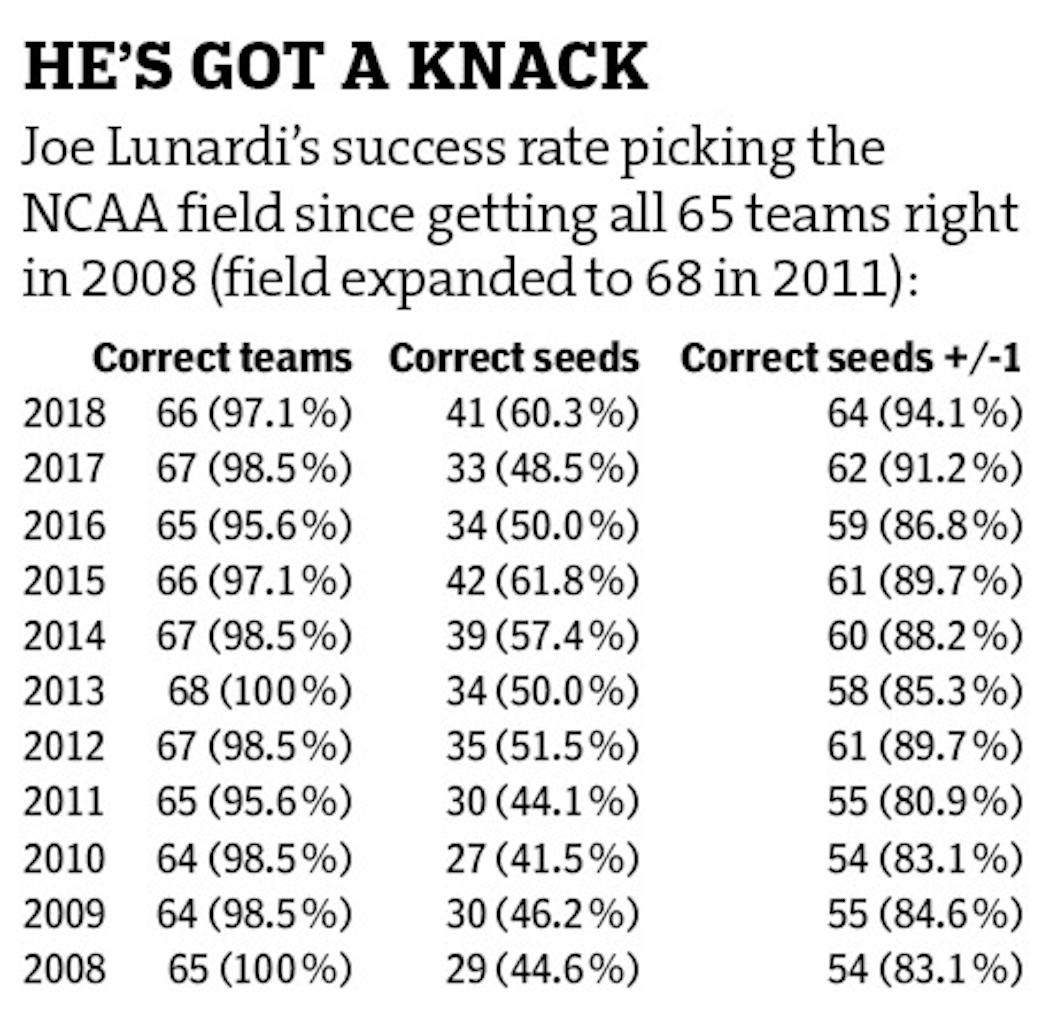

In 2008, Lunardi correctly picked the entire 65-team field. It was a moment that seemed to grow the already wide gap between Lunardi and the slew of other regular bracket projectors, a tribe of around 150.

"I don't think most of the others out there are doing it every day from November," said Lunardi, who for four years taught an online bracketology class at St. Joseph's until 2014. "Not because they're inferior, but they don't have to stay up."

Three years ago, Lunardi did need help staying up on the games. He was diagnosed with mildly aggressive prostate cancer. Doctors told him he could wait until the spring, after the season, to have surgery, but "there was no way I was waiting," he said. Lunardi was out of commission for less than two weeks and missed only a few games. He is cancer-free now but gets screened annually.

Lunardi has been a supporter for cancer research and awareness for some time. About two years before his diagnosis, middle brother Richard died after a 16-month battle with pancreatic cancer. Lunardi misses Richard's sending him messages about a "lousy tie" after watching him on TV. This fight is another of Lunardi's many missions.

"If there's a story here to be told," he said, "it is don't be afraid to get checked."

Bracketology is born

Long before "bracketology" was added to the Oxford English Dictionary, as it was in 2017, Lunardi grew up in the Overbrook neighborhood in West Philadelphia, a mile from the St. Joseph's campus. Some of his earliest basketball memories do not match the glamorous Philly Big 5 scenes of the era, though.

"I used to ride my bike to watch my older brother's intramural games," Lunardi said, chuckling. "I loved tagging along."

The family moved to Southern California while Lunardi was in high school, but he returned to his roots and attended St. Joseph's, like his father and two older brothers before him. In 1981, No. 9 seed St. Joseph's upset No. 1 seed DePaul on the way to the Elite Eight. Lunardi wrote about the magical run as an editor at the student newspaper, the Hawk.

Another big victory came that season, too. Lunardi met his future wife, Pam, but their first date was delayed from winter until April, after basketball season. Pam still jokingly calls him an "April Fool" for waiting so long to take her out.

Lunardi began a 30-year career with St. Joseph's in 1987, first as the head of media relations. On the side, his role as a contributor for Blue Ribbon College Basketball Yearbook expanded, and he and Chris Dortch bought a stake in Blue Ribbon in 1995. An 80-page NCAA tournament guide soon debuted.

That work went down in Lunardi's office at St. Joseph's. He would spend late nights with other area college hoops junkies to finish the Selection Sunday preview.

"Every Sunday at the crack of dawn, [former St. Joseph's AD] Don DiJulia would show up with coffee, doughnuts and bagels," Lunardi said. "He would say, 'Who you got in? Who you got out? You got that wrong. What do you think of this?' I don't think we had slept at all."

Soon Mike Jensen of the Philadelphia Inquirer was calling Lunardi an expert in "bracketology" — a tag that would stick as a new career launched.

"I started showing up in arenas and people started yelling 'Joey Brackets' down to the floor," Lunardi said. "I would be in airports and people would say, 'Are you that guy?' I'd say, 'Yeah, I'm that guy.' "

Man, not machine

Joey Brackets spent a lot of time being a dad, too. In one favorite picture Lunardi is holding his oldest daughter, Emily, a 3-year-old member of the Hawks contingent in 2004. The team was undefeated and made it to the Elite Eight.

"She grew up following Jameer Nelson and Delonte West," Lunardi said of the former St. Joseph's stars.

When Emily was in the seventh grade, Joey Brackets added another side gig: Coach Joe.

"It was the 2010-11 season," Lunardi said. "My daughter came to me and said, 'Help us or we're not going to have a team.' I remember thinking it was the worst possible time. I told her, 'I'll coach a spring sport or a fall sport, I'll take you surfing. But I can't add a winter sport.' "

Lunardi gave in, though. "I was a dad," he said, adding: "I literally had no idea how to make us better."

He scheduled practice on Monday nights to work around his St. Joseph's duties. Coach Phil Martelli moved his "Hawk Talk" radio show back an hour to accommodate him.

"I had a girl who led the league in fouling out," Lunardi said. "That was big. I would usually have a sub at the scorer's table after the second possession."

Emily never played hoops again. "I put out that flame for good," he joked. Lunardi left the sidelines for good, too, and attended too many plays and dances to count.

"I think I was scared of the ball," his youngest, Elizabeth, said with a laugh. "We were more theater girls, and he was a great stage dad."

Lunardi loves the juggling act. He makes enough money as one of the most recognized names in college hoops, but Lunardi likes to work. And his recent move into the Hawks athletics department fulfilled a dream. As the head of marketing, he works directly with new AD Jill Bodensteiner and her staff.

He is still Dad, especially with Elizabeth transferring closer. He is entrenched in Hawks basketball more than ever, from gameday crew boss to team radio analyst. And he's still "that guy" college hoops fans praise and pick on as March arrives.

Back on this November night in Philadelphia, he's a happy man in his happy place.

"Getting that buzz during warmups when the teams take the court and the music starts and the bands playing," Lunardi said, "that's kind of my fuel to do what I do. I'm still feeling that."

Pair of offensive tackles are first to commit to Gophers in 'Summer Splash' weekend

Twins' Correa ejected from on-deck circle, and he's not really sure why

Neal: Girma returns to United States national team and rewards fans with her classiness

Twins' inability to score in extra innings costly in wild loss at Seattle