The shooting lasted just seconds, but by the time it ended, more than 40 shell casings littered the south Minneapolis street, and eight people were bleeding from bullet wounds to their hands, feet and ankles.

Sherron Walker, crawling on the floor of a convenience store after one of the bullets shattered her foot, said she was praying the shooters didn't come into the store "and start shooting us."

The chaotic late-August scene is emblematic of an alarming trend in gun violence across the Twin Cities and nationwide. Firearms equipped with small, readily available conversion devices known as switches or auto sears are filling communities with modern-day machine guns that can empty an entire magazine with a single trigger pull.

Law enforcement and researchers place a lot of blame for the spike in gun violence since 2020 on the ease with which shooters can spray automatic gunfire. But as switches make guns deadlier, they also make them far less accurate and harder to control for even the most experienced marksmen. This is increasing the chances that bystanders are caught in the crossfire of disputes, and it is becoming more common for police to find scores of shell casings left behind at crime scenes.

Less gunfire, more of it fully automatic bursts

ShotSpotter technology, an acoustic gunfire detection system, has recorded a decline of shots fired in Minneapolis, but an increasing percentage of those shots are fired in fully automatic bursts.

The devices are small, resembling a Lego piece, and simple to install. They can be metal or 3-D printed plastic, and they are being shipped in large quantities from overseas countries such as China, or quickly made at home. They've found favor among antigovernment extremists and warring street gangs alike. Many users affectionately call them "buttons" on social media and glorify them in locally produced rap songs.

"If your friend has one or your enemy has one, you want one too," said William McCrary, special agent in charge of St. Paul's Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) division.

"It's an evil arms race."

Police in Minneapolis are recovering three times as many switches used in crimes as they did when they first started tracking such devices in 2021. Nationally, the ATF recovered 5,454 switches between 2017 and 2021 — a staggering 570% surge from the previous five-year stretch.

Not since the era of Prohibition have machine guns been so commonly used in crimes, said Thomas Chittum, an executive for SoundThinking — whose ShotSpotter acoustic gunfire detection system is used in Minneapolis — and former second in command at the ATF before retiring from the agency last year.

"It's not enthusiasts who want to have a machine gun but can't afford a legal one," Chittum said. "It's criminals who want as much firepower as they can get, and that's part of the danger."

Illegally imported, manufactured domestically or even 3‑D printed from computer files, machine-gun conversion devices — or "auto sears" — offer a way for criminals to convert some types of weapons into fully automatic versions.

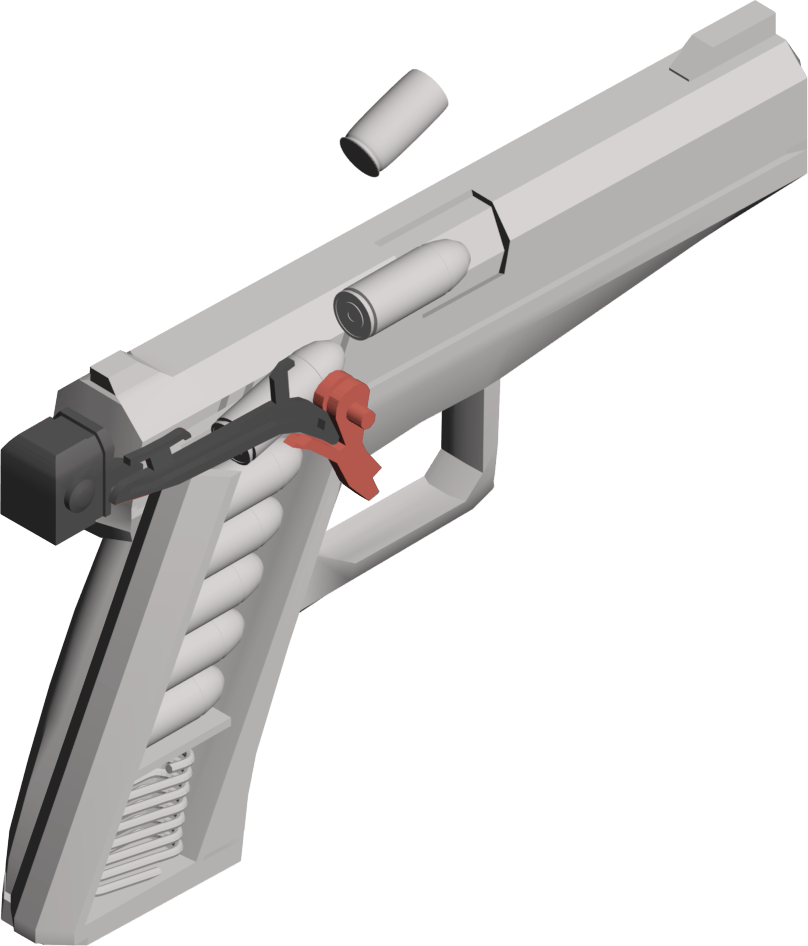

Designed for some semiautomatic pistols, switches easily convert the weapon to a fully automatic machine gun by clipping to the back of the barrel.

The switch changes the pistol's function by overriding a mechanical armature that would otherwise allow only one shot to be fired at a time.

When the trigger is pulled, contact between the switch and armature enables all the rounds to be automatically fired without repeatedly squeezing the trigger. Dozens of rounds can be fired in just a few seconds with larger magazines that hold 30 rounds or more.

Minneapolis and St. Paul police only started tracking switches in the past two years, as reports of shooters spraying high volumes of bullets began to climb. In Minneapolis, officers went from processing 4,678 discharged cartridge casings in 2019 to more than 10,600 each of the last two years.

The devices often turn up in Minnesota in the form of small, square accessories that can be fastened on the back of a semiautomatic pistol. Without the switch, the shooter must pull the trigger to fire each round. With it, the gun will continue firing as long as the trigger is depressed.

"This type of weaponry has always been around, but it's never been really readily available for the street-level individual or gang member" until now, said Minneapolis Police Sgt. Adam Lepinski, who leads the department's weapons unit.

Under federal law, the switch by itself is classified as a machine gun and is illegal to possess unless registered with the ATF.

Federal agencies started noticing machine-gun conversion parts being imported from countries such as China about five years ago, sometimes disguised as wall hangers or accessories for airsoft or pellet guns.

By October 2020, a pair of twin high school football standouts in north Minneapolis who'd joined a prominent street gang started writing posts on Facebook expressing their affinity for the devices.

"I got a Glock with a switchy you don't wanna see dis bitch get to blickin,'" Quantez Ward wrote at the time, the latter word slang for gunfire.

Weeks later, Cortez Ward was partially paralyzed in a drive-by shooting when members of a rival gang pumped more than 80 rounds into a car he was riding in. Soon after his release from the hospital, assailants shot up his home while his mother was inside with him. Police later found 20 shell casings on the street.

Cortez posted on Facebook soon after: "Let off 50 out that switch bet he can't duck em all."

The twins were charged in Hennepin County in January 2022 with illegally possessing firearms modified with switches after they were caught with the guns as they left a funeral for another gang member.

They pleaded guilty that spring and were sentenced to probation. But four days after Cortez's sentence — and a week before Quantez was due back in court for his own sentencing — the brothers were pulled over by Maple Grove police. Officers found Cortez with an unmarked Polymer80 pistol, or ghost gun, with a loaded, high-capacity magazine. Quantez Ward had a rifle in a backpack. Months later, law enforcement searched their home and found other firearms, including another ghost gun outfitted with a switch.

The twins have since been sentenced to 30 months in federal prison.

"Young people are bragging about their access to these types of weapons," said James Densley, a criminal justice professor at Metro State University and co-founder of the Violence Project, which is studying homicide trends in the Twin Cities. "That's fueling the perception that they are everywhere, and in turn that creates more incentives to go out and do what everybody else is doing."

Cortez Ward released a rap album via YouTube from jail while he awaited his prison sentence earlier this year. One of the songs, which been seen more than 1,700 times, is called "OnFully," and celebrates converting semiautomatic pistols into machine guns.

In a music video still viewable on YouTube, a defendant from another recent unrelated case is seen waving a pistol equipped with a red switch as he rapped.

Others charged in recent federal gun cases are telling judges how machine-gun conversion devices are prized for enhancing weapons already sought for protection in volatile communities. In court filings, one man's attorney said the devices were referred to as a "cheat code" because they would "guarantee victory over an opponent without an auto sear."

These are among the at least two dozen cases focused on switches that U.S. Attorney Andrew Luger's office began filing since his return for a second term last year. Switches are also referenced in fentanyl trafficking cases, as Luger has directed the office to take on charging more gun and drug cases.

"What started off as an advantage that certain people felt they had by owning a switch is becoming a necessity because it's kind of like nuclear weapons: If you got them, I need them," Luger said in an interview.

With nearly all federal prosecutors in Minnesota working on violent crime cases, Luger sent a cadre of his staff to a south metro shooting range this spring to learn more about conversion devices from ATF experts.

Wearing glasses and ear protectors, the prosecutors watched as Pete Vukovich, a special agent and chief medic for the ATF in St. Paul, attached a little gold switch to the back of a Glock pistol. He had first timed the pistol: 1.5 seconds to fire four rounds.

With the switch installed, Vukovich sat down to steady himself in front of a target and as a precaution: Pistols equipped with switches aggressively trail upward after the initial shot.

It took less than half a second to fire the same number of rounds.

"This by far is one of the scariest guns I've ever fired in my life, and I have a military background," Vukovich said. "You'll realize why a lot of roofs in Minneapolis have bullets on them."

Vukovich then retrieved an orange plastic auto sear designed to "drop in" the receivers of a rifle to render it fully automatic. This auto sear, he said, was produced by a 3-D printer. On a printer that costs about $100, Vukovich said, someone can make a single auto sear in 40 minutes. On a higher-powered $1,000 printer, it takes just 10 minutes, he said.

"When you can print something off at home and when you can learn about how to install devices or modify firearms simply by going on YouTube and pulling up a video and teaching yourself within a matter of minutes, that creates a new challenge for law enforcement and for public safety," said Densley, the Violence Project co-founder.

The ascent in popularity of pistols modified with switches is overlapping with the use of privately made "ghost guns" — firearms assembled at home from a kit or from 3-D printed materials. They typically lack a serial number, making it exceedingly difficult for police to trace them if they are used in a crime.

The ability to print firearm parts or assemble ghost guns via kits has introduced a new avenue for juveniles to get their hands on guns they otherwise couldn't legally buy.

That threat has been on full display in communities such as Brooklyn Park, where Police Inspector Elliot Faust said ghost guns are turning up in crimes at a concerning rate: Police there recovered just three ghost guns between 2018 and 2019. But by last year, ghost guns accounted for nearly one in five firearms seized in the city.

That year, twin brothers, then 17, allegedly purchased gun parts online and assembled a working firearm at home. It would become one of two firearms used in an altercation that led to the shooting death of Syoka Siko, also 17. The case is unsolved.

Faust said that Siko was in the car with the twins when the three were involved in a dispute with two other people in November 2022. Siko was fatally shot and one of the twins was shot in the leg but survived. According to criminal charges filed in Hennepin County juvenile court, one twin admitted that there were two 9mm ghost guns in the car at the time of the shooting and that they stopped to hide the guns after driving away from the shooting scene.

Prosecutors charged the twins as juveniles with illegally possessing a firearm without a serial number. But Faust said investigators still don't know who fired the shots that killed Siko.

Still, he said, the case underscored the dangers of easily assembled gun parts that circumvent background checks and what he called "reasonable measures that are put in place to prevent guns from falling in the hands of the wrong people."

"I think that everybody would agree that 16- and 17-year-olds should not be buying pistols online and possessing them," Faust said. "If you disagree with that, then I urge somebody to come in and take a look at the juveniles that we've had murdered even in our own community and explain to me why that's a good idea."

If social media can be used to glorify the possession and use of switches and ghost guns, more recent cases are also underscoring its potential to advertise and distribute them.

Federal prosecutors last month charged three young Twin Cities-area men, accusing them of taking part in a Snapchat group dubbed BLICCS&STICCS3 that allegedly advertised, sold and traded ghost guns, conversion devices and drugs around Minnesota.

According to court records, federal agents went undercover to infiltrate the group and arranged a half dozen purchases of switches during the investigation — with the devices priced between $300 and $400 apiece — and an unserialized Glock pistol. One of the conversion devices was a 3-D printed drop-in auto sear designed for an AR-style rifle.

One of the men charged, Avont Akira Drayton, 22, allegedly showed undercover officers a video of himself shooting a firearm with the drop-in device and telling them that it made the gun fire "way too [expletive] fast."

The business of trafficking switches and ghost guns can itself be a dangerous one.

According to testimony from a special agent, Kyrees Darius Johnson, 23, was involved in an attempted carjacking in St. Paul in August in which he was shot more than a dozen times by a victim who had a permit to carry a gun. During the encounter, Johnson and an unidentified passenger fired back with guns outfitted with switches, and police recovered about 40 shell casings from the scene — weeks before his eventual arrest in the federal case.

Minneapolis police have yet to make any arrests related to the south Minneapolis convenience store mass shooting in August, and the department is not commenting on the investigation.

At least two of the bystanders hit by bullets had a previous encounter with gunfire: Walker, who was shot in the foot, said she was a teenager when she witnessed the fatal shooting of her sister. Jerome Allen, hit in the elbow, had already survived a shooting when he was growing up in Chicago.

Yet for Allen and Walker, this was unmistakably different from any gunfire they've known.

"It was rapid," said Allen. "The next couple of days, I would sit in my car and I could just feel myself grabbing the back of my head. Like I'm hearing the gunshots again."

Star Tribune data reporter Jeff Hargarten contributed to this report.

Credits

Reporting Stephen Montemayor and Jeff Hargarten

Photography Leila Navidi, Shari L. Gross and Emily Johnson

Graphics Mark Boswell and C.J. Sinner

Editing Eric Wieffering and Abby Simons

Copy Editing Catherine Preus and Valerie Reichel

Design Bryan Brussee, Josh Jones and Josh Penrod