With the recent passing of Roger Bond Martin, Minnesota lost its greatest teacher of landscape architecture and one of the most influential American landscape architects of the past 50 years.

The Harvard-trained Martin helped found the Department of Landscape Architecture at the University of Minnesota in the late 1960s, and went on to teach generations of landscape architects. He also won the Rome Prize, one of the world's most elite arts and design fellowships.

And yet, few Minnesotans know his name, even though he designed projects that have defined not only the metro area, but the entire state.

His renovation of the roughly 50-mile Grand Rounds parkway system in the Twin Cities included designated bike lanes, which were rare at the time. He also led the design of the Minnesota Zoo, which was revolutionary for placing animals in their native northern landscapes.

Architect Duane Thorbeck met Roger Martin in 1961 when they worked at Cerny Associates, then a leading Minnesota architecture firm that spawned a generation of modern designers. Over the next 50 years, Thorbeck's and Martin's careers overlapped as designers, professors and business partners.

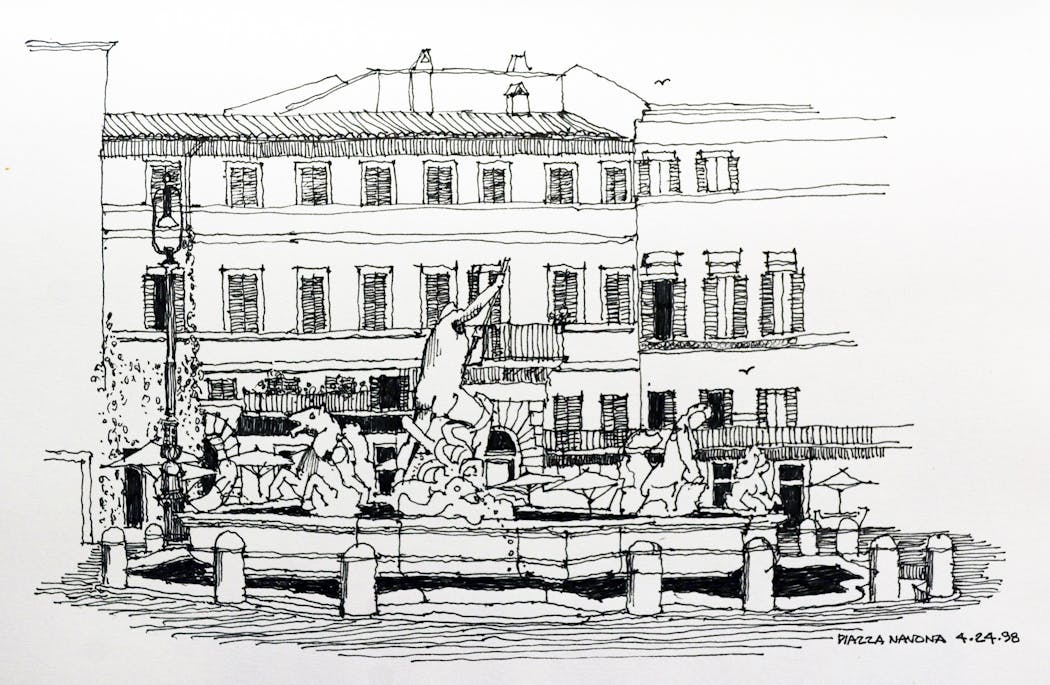

In 1962, they both won the Rome Prize and spent a year living near the American Academy in Rome, each with his own studio and creative projects. Martin, who was accompanied by his wife, Janis, had a gift for sketching — a talent that likely helped to land him the Rome fellowship and that he applied for the rest of his life in teaching and designing.

After Rome, Martin became an assistant professor at the University of California-Berkeley, teaching landscape architecture at a time when West Coast landscape architects were forging a new regional style that emphasized outdoor living, water, pathways and textured concrete. (One of Martin's colleagues was Lawrence Halprin, who later designed the original Nicollet Mall.)

In 1966, Ralph Rapson, celebrated dean of the U's School of Architecture, invited Martin back to Minnesota to found the Department of Landscape Architecture.

"Even though Roger was a landscape architect," Thorbeck said, "he always talked about design as a way to make linkages between buildings and sites. He designed and taught to consider the whole environment and to work in collaboration with other fields."

In 1968, Martin, Thorbeck, graphic designer Peter Seitz and systems analyst Stephen Kahne founded InterDesign Inc. The innovative, interdisciplinary firm became a model for bringing designers from many disciplines to collaborate on projects.

Martin also designed and planned many of downtown's first riverfront parks. Next to the historic Durkee-Atwood plant on Nicollet Island, Martin and his former student and business partner Marjorie Pitz designed riverbank walking paths and a green open amphitheater still in use today. He planned more trails along SE. Main Street and along the old rail corridor separating downtown Minneapolis from the river.

"Roger's quiet influence in transforming industrial areas as parks was astonishing," said Pitz. Thanks to his advocacy, "the Minneapolis Park Board purchased and developed land for continuous public use of the riverfront."

His early advocacy helped to save the Stone Arch Bridge as a public walkway, Pitz said.

While Martin was a passionate advocate for landscape architecture, he was at heart a teacher who taught students how to design through problem-solving.

Robert Sykes, a student of Martin's who later became a colleague, said that often "in studios and classes, the professors would gather to critique student work and Roger would say nothing, just listening and quietly sketching. Eventually he would share his comments through the sketch, not being negative about the student's work, but talking about what it could be."

Jean Garbarini, now a principal at DF/Damon Farber Landscape Architects, recalls that "Roger could tell you that your design was awful, but in a nice way. On the spot, he could make a quick sketch to steer you into a new kind of thinking."

Martin taught his students far more than the drawing, ecological and construction knowledge they would need to become registered landscape architects. He taught them the core values of collaborating, listening and designing not for art but for people.

Hundreds of Martin's students went on to shape the Twin Cities and the profession nationwide and abroad.

"The landscape architectural work accomplished by his students was his greatest satisfaction," said Pitz. "Roger's way of changing the world was teaching students who would change the world."

Frank Edgerton Martin is a landscape architectural historian, preservation planner and journalist.

Want to share info with the Star Tribune? How to do it securely

A Minnesota field guide to snow shovels: Which one's best?

Sign up for Star Tribune newsletters