Dr. Deepi Goyal had personally treated numerous COVID-19 patients, and yet the infectious disease surprised him last month when he lost taste, felt exhausted and endured soreness as part of his case.

"I consider myself quite healthy, and it really took me down," the Mayo Clinic doctor said. "Not only did it take me down, but it took me a while to recover."

Minnesota hasn't suffered the doomsday scenario of COVID-19 knocking out large swaths of doctors and nurses — leaving infected patients with nobody to care for them — but new data show the toll of the pandemic on health care workers and the need for continued use of masks and personal protective equipment (PPE) to act as safeguards.

Six percent of front-line hospital caregivers at Hennepin County Medical Center and 12 other large U.S. hospitals had blood antibody levels earlier this spring suggesting prior infections with the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, according to a new study by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The study also showed a higher rate of antibodies in 9% of hospital workers who didn't wear masks and personal protective equipment continuously during their jobs.

That difference means that caregivers not continuously wearing masks are more likely to get infected and to spread the virus to others in and outside their hospitals, said Dr. Matt Prekker, an HCMC critical care specialist and co-author of the CDC study. Among hospital workers with positive antibody tests, 44% didn't know they had COVID-19 — meaning they were unwitting carriers of the virus.

"Not an earth-shattering difference, but I think any case we can prevent, we want to do that," Prekker said.

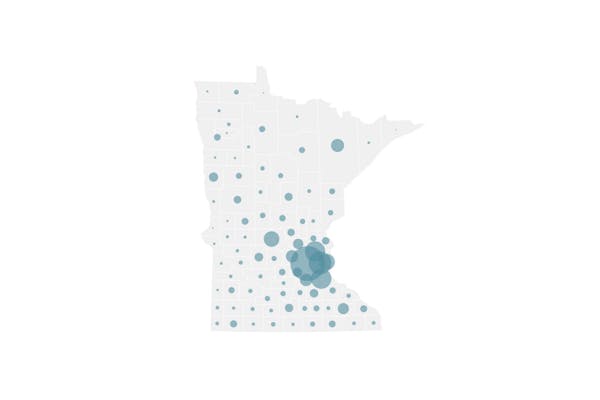

The research came as the Minnesota Department of Health reported on Tuesday that 8,396 health care workers have tested positive for infections — 11% of the 76,355 known infections in the state.

At least 380 of those workers required hospitalizations and nine died, according to state health officials, but they believe only a very small proportion of health care worker cases can be linked to exposure at work.

Goyal said he thought he cheated infection after his daughter suffered COVID-19 at her work, and he quarantined himself at home for more than a week. His first symptoms showed after nine days, even though his daughter had been recovering in isolation in her room.

"You can really do a lot within a home to quarantine; it's still very hard to stop its spread," said Goyal, though he noted his wife didn't become infected despite living with two household cases.

The state Health Department has investigated about 7,000 cases of health care workers suffering high-risk exposures from infected patients, co-workers, relatives or community events away from work. About 7% became infected, said Kris Ehresmann, state infectious disease director.

Among them, 1,940 of the investigations involved exposures in home or social settings, and 10.6% of them became infected — a higher share than with patient exposures. That has raised concerns for state health officials this summer that exposures away from work could reintroduce COVID-19 to long-term care facilities after months of efforts to protect their vulnerable populations.

The state reported six more COVID-19 deaths on Tuesday, bringing the state's total in the pandemic to 1,823. Of those, 73% involved residents of long-term care facilities who are at greater risk because of their advanced age or underlying conditions such as diabetes or heart disease.

The CDC antibody study results made sense to Mary Turner, president of the Minnesota Nurses Association. As an intensive care nurse at North Memorial Health Hospital, she has greatest access to protective equipment and has felt safer despite treating mostly COVID-19 patients.

Nurses in other settings — where mask-wearing isn't as routine and patients' COVID-19 status is unknown — have as much reason to worry, she said. "It's those situations [that are high risk] where you are around it and you don't know until it's too late."

The University of Minnesota obtained nasal samples from 500 health care workers who lacked COVID-19 symptoms this spring and conducted diagnostic tests for active infections. None was infected at the time samples were taken, according to a preprint study released in August.

The results should give confidence to patients, some of whom have hesitated to seek overdue care for heart and lung conditions or even strokes, said Ryan Demmer, an associate professor at the U's School of Public Health who led the study. "For patients who need to get to their doctor but are afraid to go because they're worried about being infected by their doctor or the health care workforce that they encounter, those fears should be somewhat allayed."

Demmer said hospitals must remain vigilant in their PPE usage, though, and he worried about overreliance on the rationing and reuse of single-use masks and gowns. A study in the August edition of the Journal of the American Medical Association found antibodies in 5,500 of about 40,000 health care workers — or 14% — but that personal protective equipment was effective for most workers.

"Health care workers remain at high-risk — higher risk than the average person. They're a very vulnerable group," Demmer said. "We still know that they're reusing PPE in an inappropriate way because of the shortage — and that's a critical shortage to address, to keep them safe."

Turner agreed, noting that hospitals have improved COVID-19 survival rates with oxygen therapies that present some risk of aerosol spread of the virus to caregivers.

The CDC study has limits, because experts still don't know if antibodies are found in all patients with COVID-19 — and whether those antibody levels diminish in some patients in the days or weeks after their infections.

Prekker said the first study looked at antibody levels after the initial COVID-19 wave in the spring, but a follow-up study will see if infection levels changed this summer when diagnostic tests and masks were more plentiful.

The CDC data showed that the infection rate was higher among the tested workers at HCMC than in the general community, but Prekker said that the level of cases in health care are strongly linked to the spread of the virus in surrounding neighborhoods.

The U study pointed to a similar conclusion. "If your community is doing well," Demmer said, "your health care workers are probably safer [if they have PPE]."

Want to share info with the Star Tribune? How to do it securely

'Safe recovery sites' would offer syringes, naloxone and more to people using drugs. The plan could be in peril.

New Minnesota GOP leaders seek peace with party's anti-establishment wing

Who is Republican Lisa Demuth, Minnesota's first House speaker of color?