Part I

The hidden wounds on Richmond Street

As a death investigator, Breanna Dibble thought of herself as the eyes and ears of the Hennepin County Medical Examiner’s Office, responsible for detecting small details that could become important clues later. On a busy July 4th weekend in 2019, she raced to the scene of a woman found hanged in a South St. Paul basement that looked like a dungeon.

Dibble went to work. Chains, sex toys, a whip, an empty tequila bottle and a polka-dot party hat spiraled in a mess around the woman’s nude body, which lay on the floor. Dibble turned her over and found bruising and lacerations smattering her back. She noticed a tattoo on the woman’s thigh, a black-ink illustration showing a female figure in lingerie with her hands bound behind her tailbone. Diamond-shaped imprints crisscrossed the woman’s throat, and they appeared to match the links of a utility chain with a Master lock that dangled from a pipe on the ceiling.

There was no suicide note. Full rigor mortis meant she had probably died hours before anyone called 911. A red dress hung off her shoulder like a scarf in what Dibble took for a clumsy attempt to clothe her. The fact that she was otherwise naked struck her as important. In hundreds of death scenes, Dibble had never seen a case of a woman hanging herself naked, especially with three kids upstairs likely to discover the body. As police questioned the others in the house, she learned at least one of them was lying.

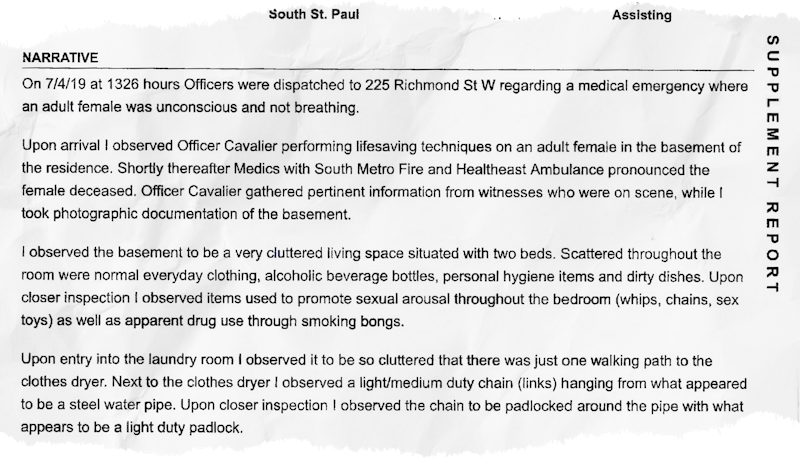

An excerpt from the South St. Paul police report on Heather's death.

The officers told Dibble not to bother with bagging the victim’s hands to preserve DNA evidence or sealing the body for the autopsy — standard protocols for a potential homicide. Dibble did anyway, but by then police had covered the woman with a dirty bedsheet, possibly contaminating the body.

“They had already made their minds up that her death was a suicide,” Dibble said in an interview. “And I had no indication of that at all.”

The woman’s name was Heather Mayer. She was 33 years old and worked as a policy specialist for a Twin Cities insurance company.

Dibble would revisit the scene of Heather’s death many times as she lay awake nights or paused at a stoplight. She waited for the day police might deliver the investigative findings that would make the rest of the pieces fit into place. It never came.

Nearly four years later, the circumstances of Heather Mayer's death continue to remain a mystery. South St. Paul police have informally continued to call it a suicide, or possibly a “tragic accident,” and the medical examiner records still list Heather’s cause of death as “undetermined.”

Dibble wasn’t the only one who wondered if there was more to Heather’s death than what police said. When one of the officers called Heather’s mother, Tracy Dettling, to say her daughter had hanged herself, Dettling’s mind flashed to her grandkids still in the house. She jumped into her car and sped toward the Twin Cities. Then she called the officer back from the road.

“Did he do this?” Dettling demanded.

Bella Bree, seen on Nov. 11, 2022, said she was in a “dark place” emotionally and financially when she met Ehsan Karam on Tinder. They married seven months after their first text.

Bella Bree was one of the last people to see Heather alive.

On a misty afternoon last summer, 29-year-old Bella smoked a Camel menthol outside the unremarkable two-story rental house where police found Heather’s body three years earlier. Being back there reminded Bella of the strange power this place on Richmond Street W. once possessed over her.

“I feel like it’s pulling me in,” she said, exhaling a white cloud.

Five years ago, Bella had fallen into a bad way. A series of debilitating back surgeries forced her to drop out of the University of Minnesota, leaving her isolated and on the verge of losing her apartment. She said she was fighting suicidal thoughts when a handsome man who described himself as “not vanilla” messaged her on Tinder.

Bella had identified herself as a “sub” in her dating profile — short for a “submissive.” She was looking for a “dominant.”

Ehsan Karam was a dominant.

It was Bella’s first real experience in BDSM — the broad term for relationships involving bondage, dominance, submission and sadomasochism — and most of what she knew came from reading “Fifty Shades of Grey,” the bestselling novel by E.L. James.

In the book, a naïve college student, Anastasia, is courted by Christian, a handsome young billionaire with a “red room of pain” in his Seattle penthouse. As Anastasia considers becoming Christian’s submissive, they meet to negotiate a contract, stipulating which safe words and hard limits Christian must follow with Anastasia in order to “explore her sensuality and her limits safely.”

Some practitioners of BDSM have criticized “50 Shades” for perpetuating dangerous misconceptions. BDSM is about safely taking or relinquishing control, they say — not the need to inflict harm on someone, as Christian does to Ana in the book, to the point of reducing her to tears.

“What people are drawn to is the idea of playing with power,” said Phillip Hammack, who studies fetish relationships as a psychology professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz. “It’s like a script” — which is why BDSM sessions are called “scenes.”

There are many forms of BDSM, but Hammack said there is one immutable rule that distinguishes all fetish from abuse: Clear — and sometimes written — consent. “If the sub says ‘peace out,’ that’s it. It’s over.”

When Bella first started dating Ehsan, he seemed like a love interest out of a romance novel. He glowed with confidence and told her that every day with her “felt like Christmas.” He paid for her meals and showered her with torrents of affection and favors they called “love bombs.” He invited her to move in with him, solving her apartment problem.

“He seemed to have all of the qualities that I would need in a partner,” she said.

In March 2018, seven months after he messaged her on Tinder, they married.

Replay video

So from the time I met Ehsan until we were married,

Bella Bree, Ehsan’s ex-wife

Ehsan was 36, 12 years older than Bella when they met. Born in Iran, he’d been raised in the Twin Cities. Up until a few years earlier, he had trained to be a professional fighter. Video from 2013 shows Ehsan winning his first pro mixed martial arts fight by choking his opponent into submission.

Ehsan didn’t respond to interview requests for this story, but in a profile published by his gym in 2013, he said bullies tormented him at school, and he started taking martial arts lessons as a kid. Training to be a fighter transformed him from a “typical insecure guy” to “a better friend, a better father, a better boyfriend, and just a happier person in general,” he told the interviewer. He talked about his expertise in chokeholds, which had won him four straight fights. An injury ended his MMA career early, he told Bella, and he worked as a security guard in downtown St. Paul when they met.

After they married, Bella began to see a more controlling side of Ehsan emerge.

He sent her a “submission contract” and said she must agree to its terms if she wished to stay with him. The document, which she shared with the Star Tribune, stipulated Ehsan would be Bella’s “owner.” He would dictate her schedule, from waking by 6 a.m. to the time she’d wait for him in bed at night. She would exercise, perform chores and eat at his direction. A poor attitude or other disobedience amounted to an offense punishable by slapping, pinching of genitals, isolation or the use of clamps for prolonged periods, according to the contract. The agreement, which Bella signed, was to terminate only in her death.

He invited other women, whom he called “slaves,” to live in their house and join them in a sexual relationship. Morgan Sargeson, 29, was the first. She recalled Ehsan introducing Bella as an ex-girlfriend whom he’d allowed to stay at his house after her mother died. Bella’s mom was very much alive, but at Ehsan’s order Bella said she spent weeks pretending to mourn in front of Morgan.

Replay video

I dated Ehsan for a month and a half

Morgan Sargeson, Ehsan’s ex-partner, sitting with Bella Bree, Ehsan’s ex-wife

Then Heather moved in. Heather had known Ehsan longer than any of them. They had dated casually once, years before Bella came into the picture. By September 2018, she was staying at the Richmond Street house four or five nights a week, before living there full time.

Heather stood on the short side of 5 feet tall, with a sugary charm that could lift the spirit of any room and an indomitability that allowed her to carry a mattress up a flight of stairs, or take a beating so Bella didn’t have to. Once, when she knew Bella was feeling especially low, Heather surprised her at work with a bucket of fried chicken, and they improvised a picnic lunch on the hood of her car.

She also carried a darkness. Maybe it started when she was raped. She was just a teenager. As she relayed the story to friends and family later, two men were giving her a ride home. They told her she couldn’t leave the car without gratifying them first.

Heather dropped out of high school and began showing signs of a severe anxiety disorder that made it hard for her to keep a job. She got pregnant the first time at 17. The father was a teenager who’d been staying under a bridge near a bead shop her mom owned, where Heather worked part time, in Northfield. Heather set out to help him, and she ended up marrying him. The relationship fell apart, and by age 25, she was a single mother of three boys.

Heather found a group of like-minded people in the BDSM community. Others had also endured sexual abuse. BDSM allowed them to take the power back by acting out scenes in which they were in total control.

She kept that part of her life secret from her family. In online forums, she called herself “CandySays2.” She became a moderator for a group of hundreds of people in the local BDSM community that met daily on social media, semimonthly in person and occasionally for parties.

Part of Heather’s role was to keep predators out of the community. If a new member sought to join her group, she and the other moderators were responsible for vetting them first. Heather was a tenacious protector of her flock — which is why her friends say they were so terrified of the images that began to appear on her social media feed.

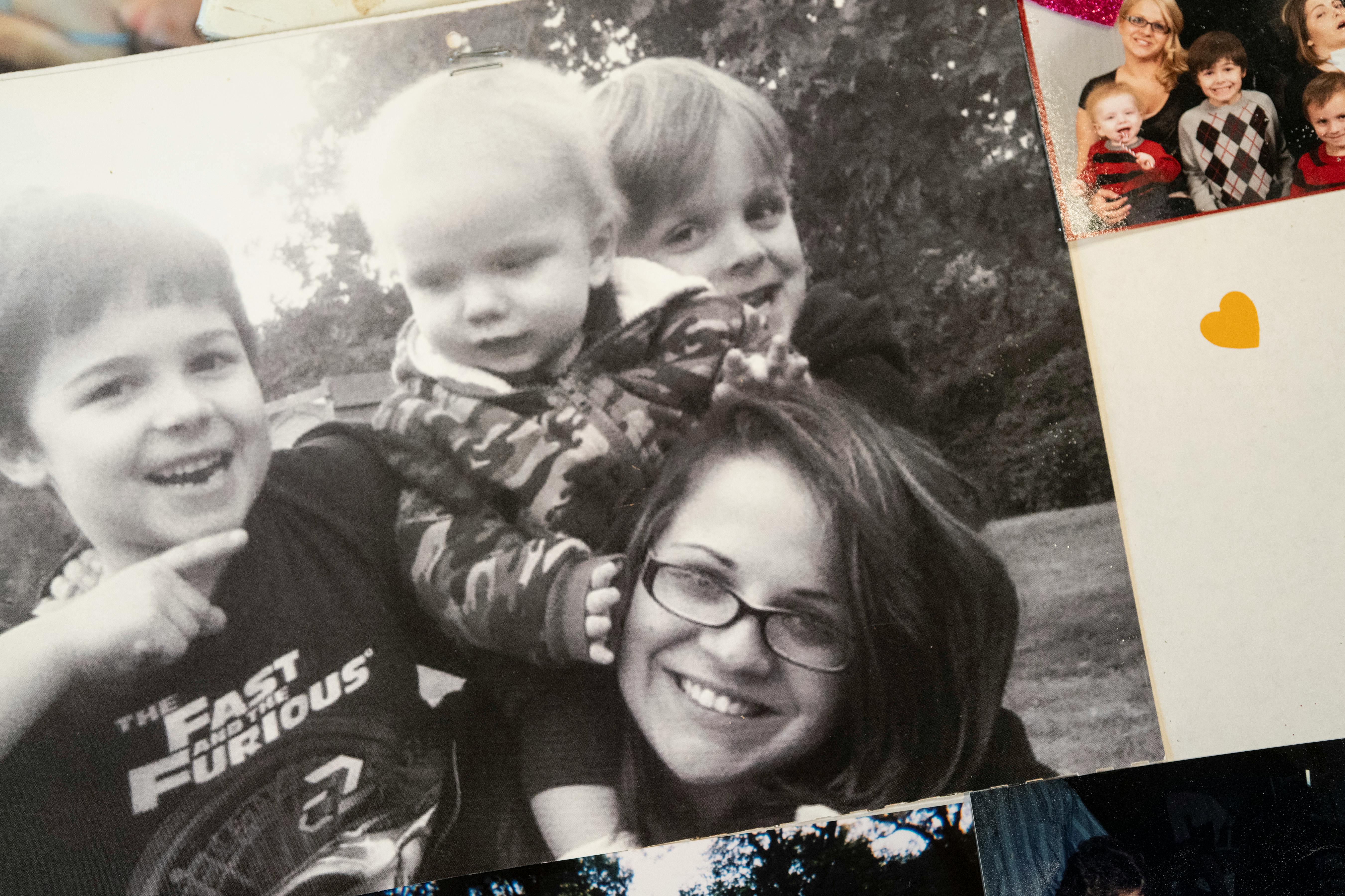

Heather Mayer is seen in a photo from her phone. The 33-year-old insurance policy specialist had a playful streak and a toughness belied by her size.

A week after agreeing to be Ehsan’s “slave,” Heather told a friend how well it was going. “I’m super happy and I feel a bigger balance than I have before and I’m loving it!” she texted.

But in later messages, she described him as a “walking time bomb” who used the pretext of BDSM to prey upon vulnerable women.

“He’s a man with mental health issues and is mentally/physically abusive and he found a label that helps him justify that abuse,” she said.

For Heather, Bella and Morgan, what had started as consensual BDSM turned into beatings that exceeded anything they’d agreed to, according to Bella’s and Morgan’s interviews with the Star Tribune and police, and corroborated by pictures, videos and private messages.

Morgan said Ehsan crossed the line separating BDSM from abuse early in their relationship, when he struck her on the inner thigh with a metal pipe. The pipe left a red imprint that bloomed into a purple and blue bruise bigger than the size of her hand, and that has yet to fully disappear more than four years later. The weapons after that day included whips, a flogger covered in sharp plastic teeth, chains, his fists and a conductor wand he used to shock them with an electrical current, she said.

“He would punch me in the ribs repeatedly until they broke. He would make sure they broke,” Morgan said. “And then he would stretch my ribs until I passed out from the pain. And then I would wake up to him doing whatever he wanted to me.”

Bella recalled several of the instances he hurt or scared her, like the time he held her underwater in a bathtub until she almost lost consciousness. Or when he shoved her face in her cat’s dirty litter box, and months later she was still finding silver grains of litter lodged deep in her ear. Once, he beat her with a metal pipe so hard it bent her wedding band and crushed her finger.

He threatened to kick Bella out of the house unless she endured what he called her “gantlet.” Bella said he beat her with his hands, a belt and a metal rod until she passed out from shock. He posted a photo on Instagram afterward, showing Bella’s nude body covered in bruising from the neck down, she said. “And people loved it.”

Both Morgan’s and Heather’s young children lived in the house at different times when their mothers were beaten. Ehsan found out Morgan was looking to move out, and “he went after my kidneys and my tailbone with various diameters of PVC,” she said. “My daughter was sleeping downstairs, so I couldn’t scream. And he knew that.”

For Morgan, the fear of staying gained the upper hand.

On the morning of Dec. 7, 2018, after Ehsan left for work, Morgan’s co-worker helped her pack and drove her to an apartment he’d rented in his name so Ehsan couldn’t follow her.

“I absolutely lived my last, like, three weeks there unsure of whether or not I was going to wake up in the morning,” Morgan said.

Replay video

I would be able to steal away to study for college,

Morgan Sargeson, Ehsan’s ex-partner, sitting with Bella Bree, Ehsan’s ex-wife

The BDSM sessions turned into a contest to see which of the women could endure the most pain, and it was almost always Heather, according to Bella and Morgan.

Images taken during that period show Heather’s body covered with dozens of red markings from a weapon fashioned with the tiny teeth of a plastic office-chair mat. A video from February 2019 shows Ehsan snuffing out a cigarette on Heather’s back and then repeatedly holding her head underwater in a bathtub, once for about 20 seconds, even after she thrashed to get back up. Weeks later, she texted Ehsan from the hospital, reporting she’d suffered pneumonia, bronchitis and an ear infection.

“I am not well,” she said in a separate exchange. “I didn’t realize that slave meant I do not get taken care of when I’m not doing well.”

“You get taken care of pretty f—ing well,” he replied. “Even making that statement is extremely ungrateful.”

“All of me aches today ... can’t hear out of my left ear ... stomach still hurts and I feel cold,” she wrote to him in another conversation.

“Suck it up, bitch,” he replied.

In other messages, she described occasions where he drank in excess. She urged him to get treatment and said he had a history of hurting his girlfriends after he blacked out. “You are going to hurt someone or kill someone someday,” she said.

Ehsan denied it. “Hypothetically,” he said, “if I had hit you, would it be wise to admit such a thing over text?”

Heather Mayer

Ehsan Karam

Three weeks after being admitted to the hospital, Heather called police to report Ehsan had attacked her and locked himself in the house with her kids. When the officers showed up, Heather said they’d broken up and he’d punched her head “five or six” times and then chased her into their alley, according to a police report. Ehsan didn’t go peacefully. Police broke out a window in his house, and he reached through the glass and snatched the barrel of one of their guns. They Tasered and shot Ehsan with three rubber bullets before he collapsed and the officers were able to break in the door.

Ehsan was taken to jail and charged with domestic assault and obstruction of justice. Heather filed for a domestic abuse no-contact order. This fight in front of her children had gone too far, she told him.

“Maybe someday you’ll get the help you need and you won’t keep hurting people,” she wrote to him in a private message on social media. “I love you Ehsan ... I will probably forever ... I hate you for taking yourself away from me.”

Heather Mayer, posing in this photo with a chain around her neck, was a moderator for a Twin Cities BDSM group. Her role, in part, was to keep predators out.

The separation didn’t last.

After the assault, she and Ehsan started exchanging texts and private messages, sometimes dozens per day. The messages make references to sleeping together and meeting outside at her job, where Ehsan worked for the building’s security. Ehsan said that a proper slave would have no limits, and that things would be different “if you’d acted appropriately.”

“I love you,” Heather replied. “This is hurting me beyond what ive really experienced before … i dont know how to navigate it … i’m scared and alone …”

“This is where you lean into your submission and my protection if you want this to work,” he told her. “Really no way around that.”

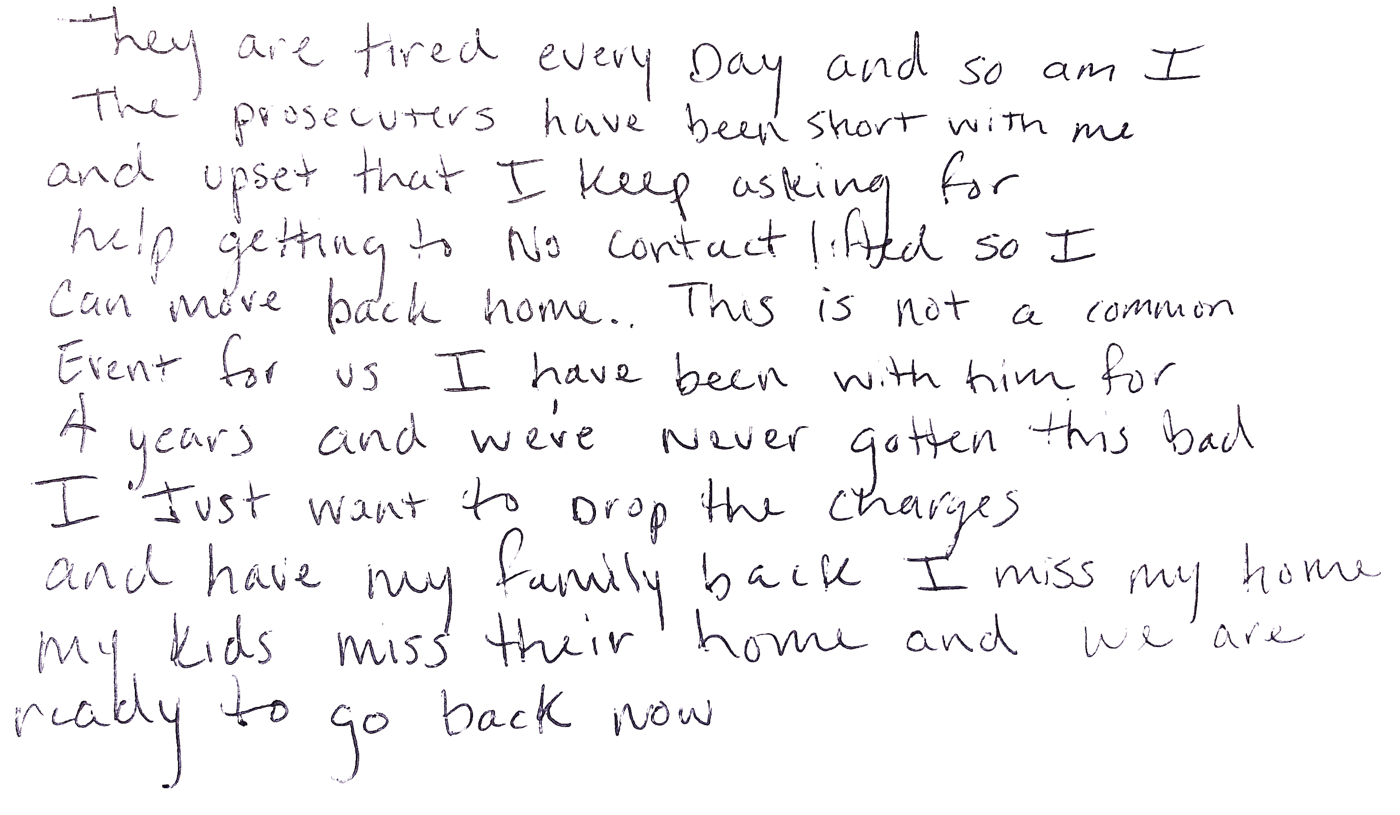

Less than two months after taking out the no-contact order, Heather wrote a letter asking a judge to lift it. She sent a draft to Jennifer Casanova-Roers, Ehsan’s attorney, who agreed to look at it before Heather submitted it to the judge. In texts, Ehsan responded with edits instructing her how to downplay the abuse, citing Casanova-Roers.

“Jenefer [sic] says if you want the no contact lifted you have to be at court on Tuesday,” Ehsan texted her on June 12, 2019. “She said there’s a part in your letter where you say ‘nothing like this has happened THIS BAD before’ she thinks it should say NOTHING LIKE THIS HAS EVER HAPPENED BEFORE.” He told her to add that she suffered from bipolar disorder and PTSD, and that she’d been erratic because she went off her medication. “And of course remove the sh— about me being drunk,” he said.

The next week, Heather stood in front of Dakota County Judge Jerome Abrams, asking that Ehsan be allowed to move back home.

“She feels safe,” Casanova-Roers told the judge. (Casanova-Roers declined to be interviewed for this story.)

Abrams remarked on the severity of the events that led to the no-contact order, but he agreed to lift it. For the sake of Heather’s kids, he said, “it’s probably good for you to get back together so long as things are smooth.”

Sixteen days later, Heather was dead.

An excerpt from Heather Mayer's journal, asking to lift the no-contact order against Ehsan Karem that she had sought in April 2019, three months before her death.

After she left Ehsan, Morgan married the coworker who’d aided her escape. She got pregnant that summer, and they bought a townhouse together in Apple Valley. When she found out Heather died, she grieved for her friend. But Morgan decided to stay out of it when people from her old life started asking her to go to the police about Ehsan’s history of violence.

She was getting ready to take her kids bowling six months later when her phone rang. The name that flashed across her screen read “Heather.”

Someone was calling her from a dead woman’s phone.

Part II

A mother’s instincts won’t let go of case

Tracy Dettling began compiling evidence after Dakota County declined to file charges in Heather Mayer’s death. Above, she held a photo of her daughter on Jan. 2, 2023, as she stood on the frozen remains of a garden Mayer had planted for her years ago in Nerstrand, Minn.

Tracy Dettling entered the prosecutor’s office braced for bad news.

It had been seven months since police found her daughter Heather dead, and in that time Dettling had lost faith that police were taking the case seriously. When Dakota County Attorney Kathy Keena called a meeting, Dettling texted the lead investigator to say she felt in her gut there would be no charges. “I hope I am wrong.”

Dettling’s suspicions proved correct.

The police investigation, Keena said, did not find criminal behavior that led to her daughter’s death because Heather voluntarily climbed into the chain harness she was found in before the others in the house went to bed, and they owed her no “duty to protect” under the law. Had Heather died in the course of BDSM — the form of sexual roleplay she and the others in the house practiced — a “strong argument could be made” for criminal negligence charges. But Keena said the evidence pointed in the other direction. (Keena would not agree to an interview for this story.)

Dettling bit her tongue and gazed across the room. There was more to this, she thought. If the police couldn’t find the truth, she would do it herself. Dettling told Keena she wanted her daughter’s file — the body-camera video, autopsy records, police interviews, Heather’s iPhone.

“I want everything.”

Heather Mayer grew up in Nerstrand attending church, local football games and going to the cabin for long weekends.

If there is such a thing as luck, Dettling believes her family didn’t get any. Her first child died of sudden infant death syndrome. A car accident left her second daughter, Jennifer, quadriplegic and cognitively impaired at 19.

“Heather was my last hope,” Dettling said.

Dettling is short, like Heather. With glasses perched on the edge of her nose and a flash of white hair pulled back into a ponytail, she spends her free time scouring police records or rereading court transcripts she keeps stacked on her dining room table, searching for clues that may have eluded police.

She raised Heather in Nerstrand, an hour’s drive south of the metro, in a modest old house that overlooks a tree-covered valley. Nerstrand is a community of only a few hundred people south of Northfield, a larger city that’s home to the Malt-O-Meal cereal factory and whose slogan is “Cows, Colleges and Contentment.” Heather enjoyed a typical Midwestern country girl’s life, attending church and varsity football games and going to the cabin for long weekends. She devoured books, especially love stories.

At 16, Heather entered what Dettling calls the “black years.” She dropped out of high school. She started sneaking out. One day, Dettling found her daughter inside a car in their driveway having sex with a stranger.

“Whatever happened to my daughter, it was like night and day,” Dettling said. “I didn’t know how to help her.”

Dettling convinced Heather to get a GED, but a crippling anxiety disorder prevented her from holding down a job. Heather worked for her mother for nine years, as her disabled sister Jennifer’s full-time caretaker. One day Dettling found Heather dozed off and Jennifer dangling helplessly out of her wheelchair. “What are you doing?!” she remembered shouting.

Heather woke up and tried to brush it off. Dettling lost her temper, and the fight ended with Heather quitting and storming out of the house.

She blocked her mom’s phone number after that. In her rare visits home, Dettling recalled, she noticed Heather losing weight at an alarming pace (by the time of her death, Heather had shed 50 pounds from what she’d listed on her driver’s license). Her daughter’s skin appeared gray and sallow, her cheeks hollowed. She wore long sleeves and turtlenecks, even in the summer.

One evening, Dettling just had this feeling. She called Heather’s son and told him to put his mother on. Heather sounded weak, Dettling recalled later, but she said she was feeling good about the future and talked about plans to take the kids to Valleyfair. They fought over Ehsan. Dettling couldn’t understand how Heather could go back to the man who’d hit her.

“Leopards don’t change their spots,” she said.

“He’s good to me,” Heather replied.

“Heather, how is he good to you?” Dettling asked. “Just name one thing.”

Heather was silent, Dettling recalled. “That said it all to me.”

Two days later, police called to say her daughter had killed herself.

Tracy Dettling cried as she talked about the death of her daughter next to piles of documents she has investigated at her home in Nerstrand.

After Dakota County declined to file charges in Heather’s death, the prosecutor mailed Dettling a USB drive. She began compiling the first of what would grow into enough documents, recordings and photographs to fill a plastic storage crate. Slowly and painfully, she pieced together the day her daughter died.

At about 1:25 p.m. that July day, Bella had called 911 to report Heather’s death. She told the operator she’d found Heather at least “15 to 20 minutes” ago.

The body-camera showed officer Mellissa Cavalier arrive about five minutes later. Cavalier rushed down to the basement to find a woman named Holly Appell, 33, a new addition to the Richmond Street house, shirtless and frantically performing chest compressions on Heather’s lifeless body. Without prompt, Holly told the officer that Heather “has bipolar disorder” when she first arrived. “The keys were right next to her,” she told the officer, referring to the chain that Heather was found in. She added that Heather had not taken her medication the day before.

The officers confirmed Heather was dead. Cavalier stepped away to call Dettling. The officers and a chaplain huddled outside in the rain and debated how to tell the kids, who had been in their rooms upstairs and oblivious to what had happened, as the paramedics rolled their mother away on a gurney.

Cavalier, meanwhile, returned to the house with more questions for Holly and Bella.

Dettling had asked repeatedly if “he” did this, she said. Who was “he?”

“She was referring to Ehsan,” Holly told her, “and no he did not.”

“Was he here at all yesterday?” asked the officer.

“Yes,” replied Holly, “but he wasn’t here when all this happened … He didn’t do this,” she repeated, claiming Ehsan had left “probably about midnight or so.”

Later, Holly approached Cavalier outside the house to confess she’d lied to cover for Ehsan. He was here when it happened. He’d slept here. He’d helped take Heather’s body down from the harness.

“We know how it looks, because of like the domestic violence,” said Holly.

Ehsan returned later that night. In a 15-minute conversation in the basement, Ehsan told Phillip Oeffling, the lead investigator assigned to the case, how Heather was heavily medicated. She “asked” for the chain harness and climbed into it “of her own accord,” and the keys were “right next to her,” Ehsan told the officer. He said he checked on her several times throughout the night. “I have no recollection of what happened after that,” Ehsan said.

Ehsan said they’d called 911 within three to five minutes after finding Heather dead that next day.

When Oeffling asked to speak to him one-on-one, Ehsan told him to “talk to my lawyer.”

Though prosecutors would list Ehsan as a suspect, there is no record that Oeffling ever followed up to interview him again.

Oeffling, South St. Paul Police Chief Brian Wicke and former Chief Bill Messerich declined interview requests about this case.

After Heather Mayer’s death, panic and a changing story

In two police videos recorded the day Heather Mayer was found dead, Holly Appell first tells officer Mellissa Cavalier that Ehsan Karam had left the house at midnight and later follows Cavalier outside to confess she’d lied to cover for Karam.

First version to police

Replay video

(feet shuffling)

The story changes

Replay video

So the guy that assaulted Heather,

In listening to audio of Oeffling’s interviews with witnesses in the months after Heather’s death, Dettling found conflicting versions of what happened the night before they discovered her daughter’s body. Neither matched prosecutor Keena’s explanation that both Ehsan and Holly witnessed Heather voluntarily climb into the chain before they went to bed.

The first version came from Holly, who told police she’d met Ehsan online and visited a couple of times that year. The weekend Heather died, she’d flown up from her home in Alabama for Ehsan’s birthday.

In a phone interview, Holly told Oeffling they’d enjoyed a quiet night at home watching TV, drinking tequila and snorting cocaine, planning a celebration for the next night. Bella went to bed first, followed by Ehsan. When Holly turned in for the night, Heather was the last one up. She remembers Heather “playing with” the chain. But, “I don’t remember full-on seeing her get into it,” she said.

There’s no definitive evidence of how Heather’s body was positioned when she was found. Holly told Oeffling when she woke that day, Heather was missing. They searched the house and Holly found her in the laundry room, strangled by the chain, which was fastened into a makeshift noose by a Master lock and wrapped around her neck. Holly said they always left slack on the chain’s noose, but when they found Heather’s body, she appeared to be leaning her weight into it, “like she was trying to do what she was doing.” They shouted up to Bella, who called 911 while Holly started CPR. “And then you guys were there within a few minutes.”

A lock and chain found in the basement where Heather Mayer died. Diamond imprints on her throat appeared to match the chain.

The second version of the night came from Bella. The first time they talked, Oeffling interviewed Bella at the house on Richmond Street with Ehsan present. Speaking barely above a whisper, Bella provided short answers to Oeffling’s questions, saying she didn’t see or hear anything the night of Heather’s death, and she didn’t remember much about the next day when the body was discovered. Heather seemed perfectly fine that night, Bella said, and added that sometimes Heather used the chain alone.

The following January, after she’d separated from Ehsan, Bella told Oeffling that Ehsan had coached her on what to say before the first interview. “It was all about just making sure I don’t say that he left her there,” she said. “That she did it herself.”

In a series of new interviews with police, Bella confirmed that she was the first to bed the night Heather died, but said she was awakened by voices in the vents coming from the basement below. According to her statements to police, she could hear Heather being whipped and saying, “I would hang myself for you.”

“He was there with her. And he left her there — chained in the basement alone. Chained by the neck in the basement, by herself, while they were doing alcohol and cocaine,” Bella told the officer. “I don’t think she took her life.”

“I don’t either. I don’t either,” said Oeffling. “You mentioned they left her there. How do you know that?”

“That’s what they told me,” Bella replied.

“And then they said to lie about it, and say that she did it all herself, and she liked to do that,” she told Oeffling. “But what they said happened was they were having a ‘scene.’ And he said he left the key with her and went to bed.”

When Bella learned the next day that Heather was dead, she told Oeffling, she had wanted to call the police right away, but Ehsan and Holly said they needed to find the key first.

Bella said she spent five or 10 minutes helping them search for the key to the lock that held the chain around her throat before Ehsan claimed he found it at her feet, “which didn’t make sense to me.” Ehsan unlocked Heather and placed her on the bed, and Bella called the police.

Ehsan and Holly instructed her to tell police Heather hanged herself, she told Oeffling. “So I did. And then he left.”

“Just to clarify, you have no information that he forced her into the apparatus?” asked Oeffling. “Do you think she was in it when she made that statement about being willing to hang for him?”

Bella knew only what she heard through the vents, she told the investigator. “My darkest suspicion is that she was in that, and she said that, and he tested her on it.”

Replay video

Last thing I saw was Heather’s face.

Bella Bree, Ehsan’s ex-wife, sitting with Morgan Sargeson, Ehsan’s ex-partner

Oeffling noted the “odd set of circumstances” to the case and said the “lifestyle” of the residents on the house at Richmond Street made it a difficult one, according to recordings of the interviews with Bella.

“It’s established that [Ehsan’s] not a nice person. But not being a nice person isn’t illegal. If we want a case charged, we have to show evidence of a crime,” he told Bella.

Bella would later send photos to the officers documenting the abuse, and social media posts from Ehsan bragging about not using safe words. In a private message, Ehsan asked Bella, “Would you die for me?” In another, he threatened to kill her and himself. In a separate message, in February 2019, he described a plan to feed Holly a “bunch of drugs” and “keep her chained up like I did you.”

Bella repeatedly told Oeffling that she was afraid Ehsan would hurt more women if police didn’t stop him. “He’s going to do this again,” she said. “I know that he is.”

As she listened to the interview recordings, Dettling realized their stories did not line up.

She noticed other details of the investigation that also didn’t make sense. Days after her daughter’s death, a psychologist who knew Heather through the BDSM community called Oeffling to report how Heather had confided that Ehsan was abusing her. Oeffling told the tipster that Ehsan appeared to be a “terrible human being,” but all signs pointed to her death being an accident caused by Heather using a “dangerous combination” of alcohol and benzodiazepines, a depressant. However, when Dettling got the medical examiner’s report, she saw her daughter’s blood tested positive only for alcohol and cocaine.

The autopsy also revealed to Dettling the extent of the injuries her daughter had suffered before she died.

Scars covered Heather’s chest, buttocks, back and legs, some up to 6 inches long, including the outline from where the phrase “Daddy Knows Best” had been carved into her forearm. The medical examiner also described more recent cuts and bruises that had not healed.

The autopsy photos show Heather’s wrists bent inward and encircled with narrow contusions. Bella told police in a statement she saw Heather’s wrists shackled behind her back with handcuffs the morning she died. She told the Star Tribune she recognized the red cuffs; she’d bought them for Ehsan as a present, she said.

Police photos from the scene of Heather’s death show a pair of red handcuffs in an open drawer of a clear-plastic storage container. A pair of scissors and a zip tie can also be seen strewn across a bed a few feet away. The photos were included as evidence in the police file, but Oeffling never asked Bella about handcuffs and he made no mention of them in his report.

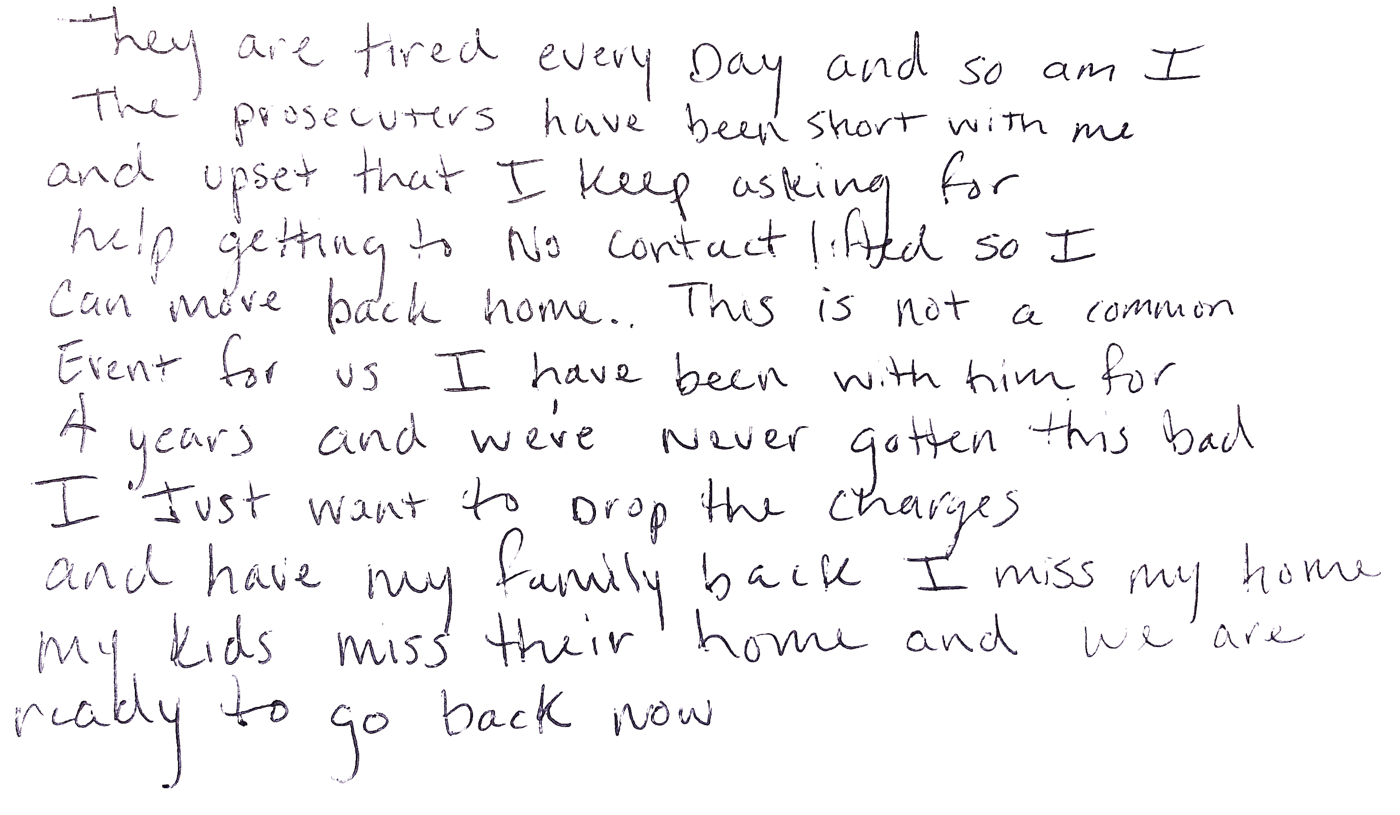

Dettling found a journal full of entries written by her daughter. One contained the phrase “I will always honor my commitments to my master” written 80 times. Another page listed her “hard limits” as a BDSM submissive, including stopping when she said “red,” the safe word. Under “special considerations,” she wrote: “Choking — I love it. If I start to get to [sic] panicked after multiple times please let me recover.”

A page from Heather Mayer’s journal contained the phrase “I will always honor my commitments to my master” written 80 times. Elsewhere she described her “hard limits” as a submissive.

Dettling guessed her daughter’s passwords and searched through Heather’s phone, including her text history and social media messages. The exchanges described past assaults and accusations that Ehsan didn’t follow the limits she’d put in writing.

“I said red so many times,” Heather said in one exchange.

“I’m in too much pain, my spine feels like it’s trying to climb out of me, every joint is throbbing and my lungs hurt,” she said in another.

“I did not think you would use kink to justify abuse,” she told him in a separate message. “You’re emotionally manipulative and do not recognize the damage you do until after the fact and then shrug it off as no big deal … you are throwing [our relationship] away by making me decide between being safe and being terrified.”

“You said you’d never leave my side,” Ehsan replied. “Quite an interesting turn of events.”

Morgan Sargeson said Ehsan Karam crossed the line separating BDSM from abuse early in their relationship. When he heard she wanted to move out, she said he attacked her with PVC pipe.

Dettling called Morgan from Heather’s phone, but at first she didn’t answer.

She texted later explaining who she was and why she wanted to talk, and Morgan called her back. Dettling said she’d found Morgan’s texts in her daughter’s phone and needed to know what happened in the Richmond Street house. Over two hours, Morgan recounted the physical and psychological torture she and Heather had endured together. Dettling said she was trying to get police to reopen the case — to get justice. Maybe Morgan’s story would convince them.

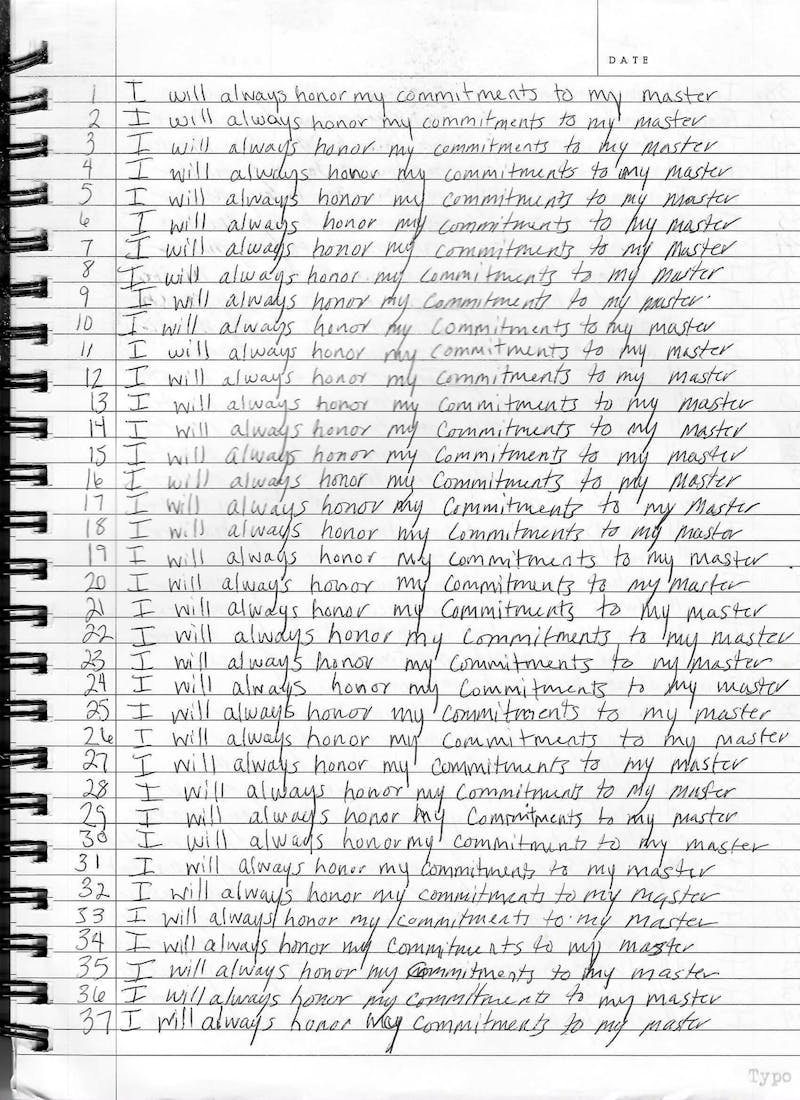

Morgan agreed to submit a statement to police about what Ehsan did to her. She sent Dettling an image from Ehsan’s Instagram account, posted shortly before her daughter’s death. It showed Ehsan crushing Heather’s face into the carpet with his leather shoe. A gob of spit had crusted over her eye. “Pray for this bitch, y’all. She’s got a ROUGH month ahead of her,” read the caption.

An image from Ehsan Karam’s Instagram account shows him crushing her face into the carpet with his shoe.

In the photo, Ehsan has wrapped Heather’s neck in a utility chain. Bella said it’s the same chain police found at Heather’s death scene.

Bella said she was there at the hotel where it happened, and she could corroborate that the protection order had been in place at the time.

Finally, months of hard work paid off. Dettling sent the photo to Oeffling, who agreed to reopen the case and interview Morgan.

Morgan sent Oeffling a video showing her bleary eyed and dressed in black lingerie. Ehsan appears behind her, grasps her neck into a chokehold between his forearms and squeezes. “I didn’t want it to happen,” she told the officer. “I didn’t want it to be filmed. So he made me drink, he made me smoke marijuana. And in the video you can see that I’m just not there at all.”

Oeffling was still skeptical any of this amounted to a crime — especially one a jury would recognize — given her willingness to engage in BDSM.

It was like two boxers entering the ring, he told Morgan, according to a recording of their interview. “You can’t come back a month later and say, ‘Hey, I didn’t agree to get my ass kicked,’ but at the time, you agreed to fight.”

Nevertheless, reopening the investigation turned up a new lead for police: Another woman who said Ehsan had assaulted her.

Her story begins the day after police found Heather dead in Ehsan’s basement.

Gabby Schmeeckle was a BDSM novice when she met Ehsan Karam over Instagram. She met Karam in person just a day after Heather Mayer’s death and fled after an “audition” where she was punched, slapped and whipped.

Less than 24 hours after paramedics had wheeled Heather’s body out of the house, Gabby Schmeeckle, 32, was finishing a nursing school exam in Omaha and then packing up her car to visit Ehsan for his birthday.

Gabby had found him on Instagram a few months earlier and they’d flirted over direct messages. He invited her up to his house for his birthday in July. Gabby also followed the social media accounts of Heather, Morgan and Bella, and she figured if these experienced women in the community had been with him, he must be trustworthy.

Gabby was a novice in the world of BDSM. After watching her dad die from complications related to an autoimmune disorder, she’d searched for something to help with the pain. She found articles that said BDSM could be an effective tool to work through trauma. “I liked the idea of being protected and cared for,” she said.

When she arrived at the house that night and met him for the first time in person, she detected a strange mood, especially with Bella, who seemed subdued and distant. No one mentioned until later in the weekend that Heather had been found dead in the basement just a day earlier.

Gabby said Ehsan invited her to join the Richmond Street house, but told her she first must endure an “audition” that entailed a weekend of pain without limit. If she asked him to stop, she would have to leave.

“I was early enough in my BDSM journey that I just kind of took it for what it was,” she said. “I didn’t really question him.”

Gabby said she fled the next night in tears, covered in cigarette burns, her own blood, whiplashes and purple and red markings across her breasts and face from where he’d punched and slapped her. She drove across the border into Iowa before she felt safe enough to pull over at a hotel for the night.

“There was no consent,” she said. “There was no saying no. This man is trained in jiujitsu. He’s an MMA fighter. What am I going to do against him?”

Replay video

A lot of my breaking point was the face smacking,

Gabby Schmeeckle,

Ehsan’s ex-partner

Over the next few months, as officer Oeffling was interviewing witnesses in Heather’s case, Ehsan persuaded Gabby to give him another chance.

She visited him in Denver, where he was staying with his mom, and he choked her until she passed out, and then choked her again because he “didn’t like how I came out of it,” she said. In November 2019, he came to live with her in Omaha for a month. “That’s when it was the worst,” she said. “Just constant torture.”

Gabby eventually filed a report of domestic abuse to police in Nebraska. They told her she had a weak case because of her participation in BDSM, she said. Police took her report, but it never led to charges.

When the officers from South St. Paul called Gabby in 2020, after reopening the investigation of Heather’s death, she told them about how he’d beat her up that first night.

“Did you tell him no?” asked investigator Mitch Nelson, according to a recording of the interview.

“Yes,” she said.

Ehsan didn’t talk about Heather’s death, she told Nelson, other than making “several comments that weekend about how he was going to be needing another bitch around the house.” She sent the detective evidence of his brutality toward her. The photos, which she also shared with the Star Tribune, showed her tattoos permanently discolored from the cigarette burns, her chest gashed and blackened from where he struck her over and over.

Nelson said he thought she had a case for a domestic assault charge. Months later, a prosecutor from Keena’s office called. The prosecutor told her the pictures were “some of the worst” she’d ever seen, recalled Gabby, but her office would not be filing charges.

“Her explanation was that a jury would never side with me.”

Replay video

He said that I had to come audition for him

Gabby Schmeeckle,

Ehsan’s ex-partner

Dettling finally caught two breaks. The Minnesota Office of Lawyers Professional Responsibility agreed to open an investigation into Casanova-Roers, Ehsan’s lawyer. Dettling had sent the oversight board descriptions of text messages from her daughter’s phone that appeared to show Casanova-Roers helping to coach Heather on how to get the no-contact order dropped.

The South St. Paul City Attorney’s Office was also charging Ehsan with violating Heather’s protection order. It was a misdemeanor. If convicted, Ehsan likely faced a fine and court-ordered therapy, maybe some minor jail time. It wouldn’t bring Heather back. But three years after her death, it would allow Dettling and Bella to confront him in the courtroom.

Before they did, another woman would come forward.

Part III

‘I want Heather’s voice to be heard’

Stephanie Chao in November 2022 at the Tucson, Ariz., spot where Ehsan Karam attacked her in front of a police officer five months earlier.

One afternoon last June, in the shadow of the Santa Catalina Mountains an hour north of the Mexican border, Tucson Police officer Maxwell McCully was driving to a report of a domestic assault when he noticed a man sprinting down the sidewalk.

McCully looked closer and saw a woman up ahead. The officer realized she was running away from the man.

McCully flipped on his siren and pulled over, but it was too late, according to his report: Ehsan tackled Stephanie Chao onto the cement in front of his squad car.

McCully leapt out of the car, unholstered his sidearm and pointed it. Ehsan surrendered and the officer handcuffed him. In his report, McCully said Stephanie was shaking, struggling to speak and bleeding from a cut under her left eye.

The cut had faded into a scar the shape of a teardrop five months later, as Stephanie sat in a park in Tucson and described how she’d met Ehsan on a dating app in 2020, after he’d left Minnesota and then Nebraska. She said they moved into an apartment his mom helped him buy, and Ehsan was training her in BDSM. Ehsan had also continued his relationship with Holly Appell, the other woman who was present the night Heather died, who Stephanie said became her “sub sister.”

Like the others, Stephanie said Ehsan bulldozed past the line separating consensual BDSM and domestic abuse. She said he choked her until she was unconscious, then again before she had a chance to recover. In less than two years, Stephanie said, he gave her a dozen black eyes.

“My one thing was I don’t want face shots,” she said. “And he would break it every f—ing time.”

The day police arrested him, Stephanie said she ran for her life. She said Ehsan punched her three times in the face before officer McCully could stop him.

Replay video

He would choke me until I was unconscious,

Stephanie Chao, Ehsan’s ex-partner

While the officers were at the apartment complex, a neighbor who’d called 911 around the same time accused Ehsan of harassing them for weeks. The officers found the neighbor’s window broken and caked in fecal matter, and four vulgar notes littering their entryway.

Ehsan was booked into the Pima County jail around 11 p.m., and charged with two counts of domestic assault, both misdemeanors. At the time, he was wanted on a nationwide warrant ordering his extradition to Minnesota for skipping a court date. Instead of shipping him to Minnesota, a judge let him out on bond at noon the next day, according to jail records.

“Oh my God,” Stephanie remembered thinking when he walked back into their apartment with no warning. “I’m going to die.”

The Tucson, Ariz., police report of Ehsan Karam’s assault on Stephanie Chao and harassment of their neighbors.

Eleven days later and 1,600 miles away, Dettling stepped up to the gray building with the words Dakota County Judicial Center in black letters over the entry, prepared to face the man she blamed for her daughter’s death.

She hoped to find a reckoning inside, even a small one. Ehsan had pleaded guilty to violating Heather’s domestic assault no-contact order, issued by a judge a few months before her death.

The South St. Paul city attorney was asking for three days in jail and mandatory counseling, far less than what Dettling had hoped to achieve when she set out on this mission to find justice. But after three years of searching, she would mark any jail time in the victory category.

When Ehsan came before the judge, Dettling watched from the spectator gallery. Bella and Morgan viewed the proceedings live through a Zoom feed.

In a plea for leniency, Ehsan’s attorney, Casanova-Roers, told Judge Timothy McManus that Heather was the one who’d initiated the contact in violation of the order, not her client. “And he understands he should not have allowed that,” Casanova-Roers said.

South St. Paul prosecutor Jerome Porter called Dettling to offer a victim impact statement on behalf of her daughter. She approached the lectern just a few feet from Ehsan. It was the first time she’d ever been in the same room as him.

“I want Heather’s voice to be heard,” Dettling began, reading from a notebook with the words “Heather case. Justice is coming” scrawled on the cover. She asked McManus to give Ehsan the maximum penalty under the law.

She told the judge how he’d inflicted so much pain and anguish on Heather that she’d suffered regular panic and anxiety attacks. “She couldn’t sleep, eat, go to the bathroom, talk to her friends, see her family, go to the store, or be with her kids or work, let alone work overtime, without his permission,” Dettling said.

“He controlled every aspect of her life, so that when I started going through her phone and reading the texts between Ehsan and Heather, it didn’t sound like my daughter,” she continued. “I knew the words were hers, but I didn’t recognize the person writing them. He had transformed my daughter, Heather, from being [an] independent, hard-working mother of three wonderful children — [a] confident and strong young woman, sure of her convictions, creative and talented — to someone I didn’t know ... He had her brainwashed. Heather couldn’t tell anymore what was love and what was abuse.

“There are laws against abusing animals in this way. What gives him the right to treat a human being in this way and get away with it? My grandchildren have to go through the rest of their lives without their mother because of this monster.”

Casanova-Roers objected when Dettling told Judge McManus how the attorney had coached her daughter on how to write the letter requesting to drop the no-contact order, but McManus overruled and let her speak.

“They crafted a letter that was a lie and presented it to this court,” Dettling continued. “It was a targeted and blatant lie ... The letter took all the blame off of Ehsan and put all of the blame on Heather.

“Jennifer used key words to sway the judge into dropping the [no-contact] order, saying to the court that Heather ‘felt safe;’ ‘they are both in therapy.’ ”

McManus acknowledged he was at a disadvantage. The case had bounced to different judges before landing on his desk for sentencing, and he didn’t know the history.

“Who are you getting this from?” he asked Dettling.

“Heather’s phone,” she replied.

“Is this after she died?”

“Yes.”

“OK,” the judge continued delicately. “And then, I’m completely in the unknown. How did your daughter die?”

Dettling bit her tongue. “It’s undetermined,” she said. “It is not suicide, as they called it in.”

She asked the judge to hold Ehsan accountable not just for Heather, but for the “pattern of abuse and torture of vulnerable women.”

“They are afraid to come forward and to make him accountable because of the extreme fear he has put in them,” she said. “I know the wheels of justice turn slowly, but I want Ehsan to know that Heather will have her justice. Your Honor, make him accountable today!”

Replay video

Heather couldn’t tell anymore

Tracy Dettling, Heather’s mother, reading from the victim impact statement she made on behalf of her daughter in court

After Dettling, Bella spoke.

She told McManus that Ehsan had also been convicted of violating a protection order she’d taken out against him. “I suffered physically, severe sexual and psychological abuse, as did Heather and the other partners he brought in and out of our South St. Paul home,” said Bella. “These abuses included being punched, slapped, kicked and beat with PVC pipes, metal-type belts and switches of various diameters all over the face and body.”

“Why didn’t you call the police?” asked the judge.

“I was in fear for my life,” Bella said. “He threatened to kill us if we did anything.”

A photo of Bella Bree with a bruised and swollen lip taken on Oct. 9, 2018. She sent this and other images to police as evidence of how Ehsan Karam crossed the boundaries of BDSM into nonconsensual violence.

When it came time for Ehsan to tell his side, Casanova-Roers told McManus he was not getting the full story. The behavior Dettling and Bella described was all “part of the sexual play” of BDSM, she said. Prosecutors for Dakota County had viewed the videos and photos and interviewed the witnesses to the allegations. “There were no charges brought against Mr. Karam because there was ample evidence to show that it was part of this BDSM play,” the lawyer said.

Heather was an experienced moderator in the BDSM community who knew what she was doing, said Casanova-Roers. “Your Honor, it’s hard to hear the things that Ms. Dettling said for anyone, especially parents. Mr. Karam has a hard time hearing it because these things did not happen in the way that they have been presented to you today.

“Heather’s death was very painful for my client as well,” Casanova-Roers continued. “He loved her dearly. And he loved [Bella] as well. I think things took a turn, and all of this consensual play that happened is now being used against him as —”

“It’s not consensual,” interrupted Bella. “It is not.”

McManus asked Ehsan if he wished to speak in his defense. In a brief statement, Ehsan acknowledged the allegations sounded bad when taken literally. “But the way that they have described it does not take into account the fact that it was all consensual. If you were familiar with the community, you would not be as shocked by what you’re hearing, I promise you, your Honor.”

In the end, McManus sentenced Ehsan to the maximum 90 days in jail.

“I find this is a serious violation,” the judge said.

The bailiff took Ehsan into custody, and Dettling grinned and pumped her fists in celebration as she left the courthouse.

Tracy Dettling pumped her fists in victory outside the Dakota County courthouse after seeing Ehsan Karam sentenced to 90 days in jail for breaking a no-contact order Heather Mayer had taken out on him before her death.

The Dakota County jail discharged Ehsan in August, after he served two months. Once released, he traveled to Orlando to stay with Holly Appell.

On Sept. 28, 2022, as Hurricane Ian raged outside, police responded to a 911 call to Holly’s apartment. Holly would later testify that she’d broken up with Ehsan, and the next morning, while they were still in bed, he wrapped his arms around her throat and squeezed her windpipe until she blacked out. “I said ‘no.’ I said, ‘I do not consent.’ I said ‘red,’ ” she told the judge. “And he told me that my words do not matter.”

Ehsan is charged with assault, battery and a first-degree felony for kidnapping that carries up to life in prison. In early March, in a courtroom in downtown Orlando, he watched blankly from the jury box as Holly testified in a hearing over his bond. Handcuffs fastened his wrists to a metal chain that wrapped around the waist of a blue jumpsuit.

In sworn testimony, Holly recounted how over the next 36 hours, until she was able to message a friend for help from her Apple Watch, Ehsan repeatedly choked her unconscious, took her phone, stripped her naked, locked her in a dark closet for hours and forced her to perform sex acts. He told her he planned to kill her and himself. “I was terrified — he had this look in his eyes,” she said.

Ehsan forced her on the bed and drew the tip of a kitchen knife from her neck to her cheeks, then stuck the blade in her mouth, Holly continued. He told her how he was going to rip off her insulin pump and let her die, she testified. “He also at that point told me that my dad wasn’t coming until Friday and that my body would be decomposing by then.”

She said she spent two months in inpatient psychiatric treatment in Tennessee recovering from the attack.

Ehsan pleaded not guilty to the charges. His attorney, Bryce Fetter, said in a court document that Ehsan’s actions with Holly during the alleged assault and kidnapping were “consensual.”

During the hearing, Fetter said that Ehsan and Holly were in a “relationship that went bad.” He argued Holly had opportunities to escape or call for help and she didn’t. Holly also had a history of dishonesty, Fetter said, and he read text messages entered into evidence showing her friends calling Holly a serial liar, saying she’d hidden her relationship with Ehsan from them.

The judge denied Ehsan bond, meaning he’d remain in jail until his trial, scheduled for June.

In an interview three days after the hearing, Holly said she now looks differently at what happened to Heather and how Ehsan reacted than when she first gave her statement to police almost four years ago. When she defended Ehsan to the officers the day they found Heather’s body, she said she truly believed the man she loved — whose responsibility was to protect his submissives — was not capable of hurting one of them. But now she knows that’s not true.

“Ehsan disguised abuse as BDSM,” she said. “He has violence in him.”

Holly said she was getting ready for bed the last time she saw Heather alive. She watched Ehsan take Heather into the laundry room and heard them engaging in a BDSM scene from the next room. “I could hear the two of them ‘playing,’ ” she said.

Ehsan came out of the laundry room, but Heather never did. “He told me she wanted to sleep in there,” said Holly.

Holly didn’t see Heather again until the next day, when she found her hanged to death in that room. She said Ehsan seemed distraught as they searched for the key to the chain around her neck, but he “freaked out” when they talked about calling 911. He instructed her and Bella to lie to police and say he hadn’t been at the house when it happened, Holly said. And then he ran.

When she thinks back on that night, Holly wonders if Heather would still be alive if she would have gotten up to check on her.

“I really feel like the only people that know what happened are him and Heather,” Holly said. “And obviously Heather can’t speak for herself anymore.”

Holly Appell testified that after she broke up with Ehsan Karam, he repeatedly choked her unconscious, locked her in a closet and forced her to perform sex acts. Karam’s attorney said the actions were “consensual.”

Holly is the sixth woman across four states to accuse Ehsan of assault since Heather called 911 on him in April 2019, according to police records. One of those, who participated in this story but asked not to be attached by name to this detail, reported to police that Ehsan forced her to perform oral sex on men in exchange for drugs. The allegation led to no criminal charges. Several said Ehsan posted explicit photos of them, which they’d shared with him privately when they were dating, on social media after they broke up. In one case, the woman said he posted the photos on her own social media account, which her family members followed. For the assault on Heather in April before she died, Ehsan was convicted of obstruction of justice and sentenced to probation; the domestic assault charge was dismissed nearly six months after Heather’s death.

Four of the women took out protection orders against Ehsan, and he’s been convicted of violating two: Bella’s and Heather’s. He is still facing charges in Arizona and Florida for allegations of assaulting Stephanie and kidnapping Holly.

Heather’s death has spread through social media as a cautionary tale to others in the BDSM community. The fact that it’s still unsolved sends an implicit message, said Sarah, another member of an online BDSM group, who requested that her last name be withheld for privacy.

“We’re not worth pursuing if anything happens — because we asked for it.”

On Dec. 20, Casanova-Roers entered into an agreement with the Minnesota Office of Lawyers Professional Responsibility to suspend her law license for 60 days and place her on probation for two years. The investigation, initiated by Dettling’s complaint, found Casanova-Roers violated Minnesota’s rules of professional conduct when she gave Heather legal advice on how to get the no-contact order lifted. Casanova-Roers failed to disclose to Heather that her interests as Ehsan’s attorney directly conflicted with those of his victim, the agreement states. The Minnesota Supreme Court enacted the suspension in May.

Jerome Abrams, the judge who dropped Heather’s protection order 16 days before her death, declined to comment. Court spokesman Kyle Christopherson said Abrams, who is retired, did not recall Heather’s hearing, but that such cases are difficult because judges must rule based on the information presented at the time. “If they’re deceived, then perhaps the ruling isn't going to be in the best interest of the parties,” he said.

Morgan and Bella have started a nonprofit to help victims of domestic violence, called Heather House. Reconnecting over the case ignited a close friendship. They are now roommates. They published a webpage called “What Happened to Heather?” which contains their accounts of the abuse they suffered under Ehsan as a warning to others. Bella plans to reenroll at the University of Minnesota and finish her degree. She served Ehsan with divorce papers while he was in jail. They officially divorced in December.

Dettling has continued to search for justice for her daughter. She hired a private detective, Mike Lewandowski, to review the case. The former St. Cloud police officer and investigator told the Star Tribune that the South St. Paul officers overlooked red flags from Day One of the investigation in Heather’s death, starting from when they told Dettling her daughter killed herself. “The term ‘suicide’ probably should have been not used,” he said.

Lewandowski said police continued to mishandle the case by throwing a bedsheet over Heather’s body, failing to preserve the scene, interviewing witnesses in front of Ehsan and by not investigating Bella’s statements about what she saw and heard that night and the next morning.

In September, Lewandowski brought the case to the Bureau of Criminal Apprehension, which assigned an investigator to review it.

The case is still open.

Ehsan Karam at a March 3 bond hearing at the Orange County Courthouse in Orlando. He is charged with assault, battery and a first-degree felony for kidnapping that carries up to life in prison.

In those first couple Thanksgivings after Heather died, Tracy Dettling could hardly eat.

She tried to make the holiday nice for the grandchildren that first year. They needed that, she thought. She went to wake Heather’s youngest son and noticed he’d written the words “Come back mom” in a sharpie on his upper thigh. She was preparing a stuffing later, and all she could think about was that funny mask Heather made every year with Saran wrap or a Ziploc bag to keep from crying when she chopped the onions, and Dettling’s brave face would quiver and then collapse.

This past November, on the fourth Thanksgiving since her daughter’s death, a half hour before the guests were set to arrive, Dettling anxiously checked on the side dishes in the oven, worried she might overcook them. She bumped into her husband, who was carving the turkey in the kitchen, and she laughed and pinched the back of his pants. When it came time for the onions, she decided to make a Saran-wrap mask over her glasses, just to see how well it worked.

Since Heather’s death, the court has granted Dettling full custody of her three grandsons. They have grown tall and sturdy, already towering over their grandmother and sprouting facial hair. The second-oldest volunteered to slice the bread and help make the stuffing — the duties his mother performed each year before she died. He ribbed Dettling about cooking too much food — again — and told jokes to fill the time when everything is cooking and the guests had yet to arrive. He remembered the time they all drove up to the Twin Cities with Heather to see “The Hunger Games: Catching Fire.” They had to sit in the very front row of the megaplex and all their necks hurt for days after. Jennifer, who was strapped to her electric wheelchair, acknowledged by blinking. A chubby Chihuahua named Margarita watched from under the table.

Dettling laughed at her grandson’s jokes and it reminded her of how Heather would make her laugh. She told them all how she spotted a cardinal earlier that day venturing up to the bird feeder on the back deck that hangs over the forest behind her house. Whenever they see one, she explained, “We always say, ‘ah, Heather’s peeking in on us.’ ”

There was a knock and the sound of the dinner guests walking in the house, and Dettling moved to the door.

Heather Mayer and her sons.

How we reported this story

The reporting for this story began in 2021, when Tracy Dettling contacted Star Tribune reporter Andy Mannix regarding the unsolved death of her daughter, Heather Mayer. Dettling was convinced police had not conducted a thorough investigation, in part because of Heather’s lifestyle in the BDSM world.

What began as a story about a mother’s search for justice expanded in scope as Mannix began investigating the events leading up to the death of Heather, and how law enforcement and the courts handled her case. About a year into the reporting, Ehsan Karam, the man Heather was living with at the time of her death, was charged with assaulting women in Arizona and Florida. Others who knew Ehsan, including his estranged wife, came forward to police alleging that Karam had assaulted them as well, and they agreed to share their stories with Mannix.

The story relied heavily on records — both public and non-public — obtained through data requests and provided by sources, as well as dozens of interviews. Mannix and photographer Renée Jones Schneider also traveled to Tucson, Ariz., Omaha, Orlando and several locations in Minnesota to complete the reporting.

The description of the South St. Paul Police Department’s response on July 4, 2019, comes from a combination of body-camera footage from multiple officers, crime scene photos, Hennepin County Medical Examiner records, police reports and interviews with people who were present that day. The reporters interviewed experts in the BDSM subculture and members of an online BDSM group Heather helped moderate. Several talked on the condition of anonymity, citing concerns that stigma around their lifestyle could negatively impact their families and professional lives.

The quotes from police interviews with witnesses come from the official recordings of those conversations made by the officers, supplemented by the officers’ notes and reports. All dialogue from court proceedings is quoted verbatim from transcripts.

Many people named in the story declined or ignored requests to be interviewed, including: Ehsan Karam, Jennifer Casanova-Roers, Kathy Keena, South St. Paul Police Chief Brian Wicke, former Chief Bill Messerich, officer Phillip Oeffling and other members of the South St. Paul Police Department. To represent their side of the story, Mannix quoted their statements on the case from police reports, court records and transcripts, interview recordings, body-camera footage and their writing.

Tracy Dettling gave Mannix access to Heather’s phone, which contained the text and private social media messages cited in this story. The phone also contained videos and photos of the violence described in the story. To corroborate their allegations, other women in the story also provided text messages, photos and videos of the verbal abuse and physical violence they endured. They allowed the Star Tribune to independently view all materials cited in this story, including those turned over to law enforcement. Some of the photos were posted to social media.

The description of the meeting between Dettling and Keena comes from a combination of interviews with Dettling and a copy of the letter Keena wrote explaining why her office did not file charges. Dettling also shared her correspondence with law enforcement over the case.

In cases where no record existed, the reporters relied on interviews with the people who were present to recreate those scenes, such as the final phone call between Dettling and her daughter.

Every minute nearly 20 people are victims of intimate partner violence, according to the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence. If you’re a victim, help is available through organizations such as the Minnesota Day One confidential crisis hotline (1-866-223-1111) and the National Domestic Violence Hotline (1-800-799-7233). If you’re having suicidal thoughts, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 988.

Contact reporter Andy Mannix if you would like to share your feedback on this story. You can also share your feedback with Star Tribune editors at editor@startribune.com.

Credits

Reporting Andy Mannix

Photography and Videography Renee Jones Schneider

Editing Eric Wieffering, Deb Pastner, Emily Johnson, Jenni Pinkley, Mark Vancleave, Abby Simons, Trisha Collopy, Valerie Reichel

Design Anna Boone, Josh Jones, Josh Penrod, Greg Mees

Development Anna Boone, Jamie Hutt

Audience Engagement Nancy Yang, Sara Porter, Ashley Miller