WARROAD, Minn. — Warroad, population 1,820, didn't say goodbye Friday to arguably the greatest player Hockeytown USA and the State of Hockey ever produced.

There is no word for goodbye in Henry Boucha's Ojibwe language.

Cousins and grandchildren, friends and family, a fellow Olympian and a former opponent alike traveled from near and far to Warroad Gardens arena, where about 800 people attended a remembrance ceremony for Boucha. He died Sept. 18 at age 72.

They did so for a former NHL player, 1972 Olympian and Minnesota state high school phenomenon who skated the Warroad River in moonlight in his youth and first played using a can wrapped in tape instead of a puck.

Warroad calls itself Hockeytown USA, and Boucha might have had as much to do with that as the Christians, Marvins and Robertses, the town's founding hockey families. Friday's eulogists included Warroad boys hockey coach Jay Hardwick, the grandson of famed coach Dick Roberts. On Friday, he suggested Boucha's legend is "part of Minnesota folklore, right up there with Paul Bunyan."

The gathering filled most of the 400 seats on the arena floor while others sat in the bleachers above. Flowers adorned a stage that featured photos of Boucha flashing throughout his life. His casket was open throughout Friday afternoon's service, as it was during traditional Anishinabe ceremonies that on Thursday night and Friday morning included drumbeats, feathers, tobacco, whistles and the burning of sage.

Red Lake Nation College President Dan King was looking for a fourth face on his proposed Indigenous athlete Mount Rushmore, after already proposing Boucha, Jim Thorpe and Billy Mills. Thorpe was the first Native American to win a gold medal, two of them, in fact, in the 1912 Olympics. He played pro football, pro baseball and basketball as well. Billy Mills won gold in the 10,000 meters in the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, one of the Summer Games' great upsets.

Boucha's electric play led tiny Warroad to the state tournament's championship game against mighty Edina in 1969, the year the one-class tournament left St. Paul Auditorium for shiny new Met Center. The place was packed. Boucha was knocked out of the game after one period when he was checked hard into the boards.

Edina won 5-4 in overtime.

"One of the speakers today said he's the best hockey player to come out of Minnesota," said Jim Knutson, a defenseman who played for Edina in that game. "I agree with the guy. Nobody dominated the game like Henry."

The military, the Olympics

The next year, Boucha was drafted with a low number — in the military, not the NHL. That wouldn't come for another year, when the Detroit Red Wings picked him in the second round.

"That's one draft you didn't want to be a first-rounder," 1972 Olympic teammate Craig Sarner said.

Sarner and Boucha played on the same line in those Olympics after the Army released Boucha to play for his country.

Boucha's Ojibwe name, Ogichidaa, means "warrior." Sarner just calls him tough, recalling the game-opening faceoff against mighty Czechoslovakia and its star centerman Vaclav Nédomanský in Sapporo, Japan. He apparently put a hockey stick made back home in Warroad to good use.

"Hank buried that Christian Brothers stick up to the 'H' in Nédomanský's stomach and he never came into our zone the rest of the game," Sarner said from his Orono home.

The U.S. won 5-1 on its way to an unexpected silver medal. That was something of a miracle itself.

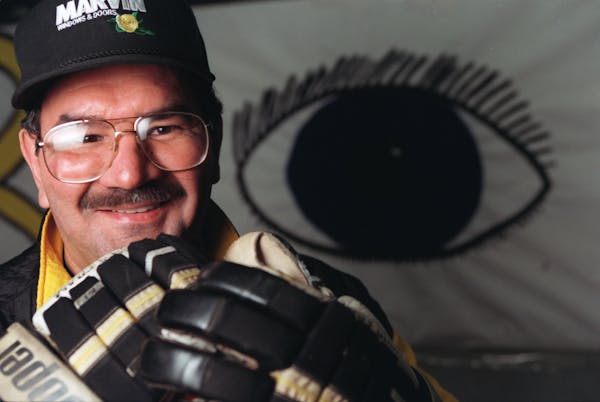

Boucha played two-plus seasons in Detroit before he was traded back home to Minnesota and the North Stars. Before he went, Boucha posed for an iconic photo that still hangs in the Warroad arena: skates and his signature headband on, hair flowing.

"When he had his hair flowing like that, he was sending a message," King told the gathering. "It was, 'I'm here and I'm Native and I'm proud.' That was the message. To me, Henry was a badass."

Bill Baker, gold medalist for the miraculous 1980 Olympic team, on Friday drove 3 ½ hours from his home and back with his Gophers defensive partner Bob Bergloff to attend Boucha's funeral.

"Henry, I considered him a friend," Baker said. "When I was a kid, five years younger than him, I watched him. He was my hero. Then I got to know him later and we had a lot of things in common. We got to know each other pretty well, and I thought it was the best I could to pay my respects."

Not goodbye

Knutson drove six hours from his Bloomington home.

He was that guy, the Edina player who checked Boucha into the boards and into the hospital after Boucha's eardrum ruptured. Knutson received a minor penalty for elbowing. He and his father visited Boucha the next day. They played together that next summer and maintained a friendly relationship through the years.

More recently, Knutson provided advice on doing a film series about Indigenous Olympians. The first film — starting with himself — was nearing completion when he died.

"There was no ill will," Knutson said. "We both have a mutual respect for each other and that led to a friendship."

He said he was booed regularly after that. The only time it bothered him was when he made the all-tournament team that year — Boucha did, too — and he saw a picture of himself in the paper.

"I'm the only one not smiling," Knutson said.

Both Baker and Knutson came to pay their respects and say farewell.

Or not.

"We're not saying goodbye," King said. "We say we'll see you again."

Twins rally against Mariners with three last-chance runs and a bunch more in the 10th

Playing without their star, Lynx keep things perfect with comeback at Phoenix

Buxton returns to top of Twins lineup and to his post in center field