When the door slammed, Henry Boucha never saw it coming. He had little reason to look. He was in the NHL and could just feel the big bucks about to happen. Good times? They were always high on his agenda.

Then . . . thwackkkk!! One disgusting hockey fight and his career was over at 24, his sight practically cut in half. His life never would be the same.

"It was like walking out a door and the door closes and `Now, what am I going to do?' I just wasn't prepared to walk out that door," Boucha said. "There were some trying years. I lost my livelihood,that's all. I guess not until you get older can you put things in perspective."

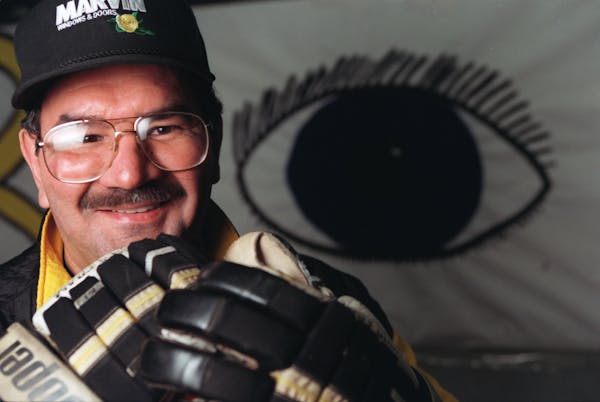

Boucha is older. He is 36, wears glasses and is 30 pounds beyond his playing weight of 205. He is soft-spoken and short-spoken, friendly but uneasy. He is the direct descendant, five generations removed, of the Ojibway chief who settled Warroad, where he's been for 16 months now. He lives in a modest apartment just a slapshot away from the rink whence he emerged 18 years ago as, arguably, the best high school hockey player in Minnesota and, forever, a storybook character in state tournament lore.

His days are very flexible. His major responsibilities are being a father to his 16-year-old daughter, Tara, spending time with his parents - "He makes a pest of himself," Alice Boucha, his mother, says with a loving chuckle - and coaching Warroad's Bantam B hockey team.

He does not work for a living. Dave Forbes and an out-of-court settlement took care of that.

On Jan. 4, 1975, Forbes of the Boston Bruins and Boucha of the North Stars left their respective penalty boxes after serving seven minutes for fighting. Forbes, chasing Boucha from behind, punched Boucha with the handle end of his hockey stick and the wood slammed into Boucha's right eye. After Boucha fell to the ice, Forbes kept whacking him.

"I couldn't understand why he'd do something like that," Boucha says, still baffled a dozen years later. The incident prompted a well-publicized aggravated assault trial in Minneapolis, ending with a hung jury and Forbes going free. It also triggered a Boucha civil suit against Forbes and the NHL. It brought Boucha 30 years worth of monthly payments to keep himself going - not rich, just going.

The injury deepened Boucha's love for drink. "It really broke his heart," said his mother. It destroyed his second marriage; his first,out of high school, had ended earlier.

The right eye is partially blind. Scar tissue surrounds the eyebrow. Depth perception is off. The injury punctuates his career.

"I hate to be remembered that way," Boucha said. "That wasn't part of the game. It was just an ugly incident. I wish I could have played another 10 years just to prove to myself I could have done something."

Oddly, the other unforgettable Boucha chapter also involves pain.This was the state tournament final in 1969, between Warroad and Edina, between the tough fishermen's sons from the Lake of the Woods and the well-groomed offspring of the nouveau riche from the suburbs. Boucha was knocked out of the game in the second period, his left eardrum broken by a high check. Edina won 5-4 in overtime with Boucha off the ice.

"Me getting hurt was just as much my fault. I had my head down,"said Boucha, who accepts violence and fighting as hockey ingredients. "It wasn't a clean hit, but years later you kind of learn to keep your head up. Out to get me? I don't know. Maybe they were, maybe they weren't."

That was his final game as a dominant, smooth-skating, creative high school player.

"Maybe, when he got to the NHL, he couldn't handle life in the fast lane, I don't know," said Cal Marvin, the operator of the Warroad Lakers senior team and a long-time Boucha observer. "But nobody played the game like Henry Boucha did in high school. How many guys can actually bring you out of your seat when they have the puck? Henry could. Never take that away from him."

The NHL was different. In Detroit, he scored 34 goals in 159 games over two-plus seasons. With the North Stars, he had 15 goals in 51 games before being hurt.

"I wish I had been more dedicated," is how he puts it now, which means he wishes his work on the ice matched the quality of his nights on the town. He does not deny his reputation as a heavy boozer.

Detroit had him after his time as a U.S. Olympian and traded him two years later. The North Stars had him, he got hurt and they discarded him. He jumped to the World Hockey Association, his vision double, his skills cut in half.

He was finished. He was down. He moved to Idaho, where some relatives lived. A retail meat business he owned in Spokane, Wash.,went under. He took a bath. He reached his settlement with Forbes and the NHL, enough, his lawyer said then, "to take care of Henry for life."

Two Thanksgivings ago, on a visit to Warroad, his daughter said she wanted to live with him. He said, "Fine. I love you. Sure." But Tara didn't want to move to Idaho. She wanted to stay in Warroad. Boucha returned to the town where his portrait still hangs in the lobby of the Memorial Arena. Once settled, the local hero gained a new position in the community - coach.

"Henry's told me that this year is the best thing that ever happened to him," said Celeste Cain, the mother of one of Boucha's players.

If nothing else, the bantam responsibility fills his morning. The contact with the boys - Boucha's 10-year-old son, Henry Jr., lives in St. Louis Park - gives some meaning to his day. "It keeps him out of trouble," said Boucha's girlfriend, Elaine Olafson.

"Oh, he still likes to have a good time once in a while," his mother cautioned, but last Sunday seemed typical. Boucha drank coffee, smoked cigarettes and watched TV before heading for the arena, sitting with old friends and cheering for the Lakers during a fight-filled Southeastern Manitoba Hockey League game.

That entertainment completed, Boucha drove his beat-up green Chevy pickup to a party convened in his honor by the 14 boys who play on the bantams. It was potluck dinner and the kids who weren't born when he was a star were calling him "Henry" and telling of once reading his name in the "Guinness Book of World Records." Until 1981, Boucha held the NHL record for the fastest first goal of a game, six seconds.Others talked of knowing him because of that picture of him at the rink.

But then one boy simply walked up to Boucha and said, "Thanks for being our coach." And another presented him with a blue corduroy jacket as the others pleaded, "Speech, speech."

Boucha's bad right eye blinked quickly. No tears, but no words either. "Practice at 7 in the morning Tuesday," is all Boucha said as the crowd turned to watch a videotape of one of their games and Boucha surveyed the scene, pushing his glasses tighter up the bridge of his wide nose.

"This is the best place to live, really," he said. "I guess being back here I've come to enjoy the simple things in life."

This weekend, Boucha will be in St. Paul at the hockey tournament. He'll be in the Warroad cheering section, another face in the crowd.

Byron Buxton drives in five runs as Twins trounce A's

Twins' Lewis searches for his way out of another hitting slump

On Vikings' rebuilt D-line, less playing time may be a good thing

Jefferson says he knows his presence at Vikings OTAs 'makes a difference'