Henry Molaison lived in relative obscurity, but he had one of the world's most famous brains.

Known to generations of scientists and psychology students as H.M., Molaison lost the ability to form new memories after surgery removed part of his brain. By agreeing to be studied over several decades, he transformed the way that we understand memory.

Molaison was a smart, technically minded man. But from childhood, he was plagued by seizures, and as he grew older, the seizures and medications he took for them interfered with his life.

The surgery, performed in 1953, was meant to help that. The operation reduced Molaison's seizures, but it also left him unable to remember anything new for more than about 20 seconds. He couldn't develop a career or form relationships.

H.M. died last December, but science is far from being finished with his brain.

Molaison, a Hartford, Conn., native who often expressed a wish to help people, donated his brain for research. It sits in the lab of neuroanatomist Jacopo Annese, director of the Brain Observatory at the University of California, San Diego, where researchers have big plans for the organ.

On Wednesday, a year after Molaison's death, Annese and his team will cut the brain into thousands of slices, the first phase of a project that will debut new technology as it preserves the 83-year-old brain.

The work will produce highly magnified images of the brain that will be available on the Internet, plus a physical collection of tissue slices that can be used by researchers worldwide. It will offer a digital map of Molaison's brain in extremely fine detail, a way to reexamine theories based on examinations of H.M. in life, perhaps leading to new insights into the mind responsible for so much of what we know about memory.

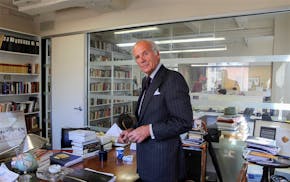

"H.M. captivated people's curiosity," Annese said. "We want to make this contribution as long-lasting as possible."

HARTFORD COURANT

JD Vance, an unlikely friendship and why it ended

Lewis Lapham, editor who revived Harper's magazine, dies at 89

Body of missing Minnesota hiker recovered in Beartooth Mountains of Montana

Mike Lindell and the other voting machine conspiracy theorists are still at it