Abaas Noor stood in front of two dozen other first-graders at Gideon Pond Elementary in Burnsville and started reading from a book he had written himself.

As Abaas told his classmates about his favorite foods and the holidays he celebrates with his family, teacher Elisa Odegard prompted him take a moment to show his classmates the pictures he'd drawn of his family.

The students' books about their cultural identity serve several essential functions at the outset of a new school year for Odegard's first-graders: Students get more comfortable with their classmates and she gets a sense of how well they can read and write.

"It's all of those little things that come together to boost achievement," Odegard said.

Minnesota schools continue to struggle to regain ground lost during the pandemic, demonstrated in sagging test scores and more chronically absent students. Those problems are often particularly vexing at schools here and around the country where many of the students' families live at or below the poverty line.

But there are bright spots like Gideon Pond, where educators have found success, even though nearly two-thirds live in low-income households.

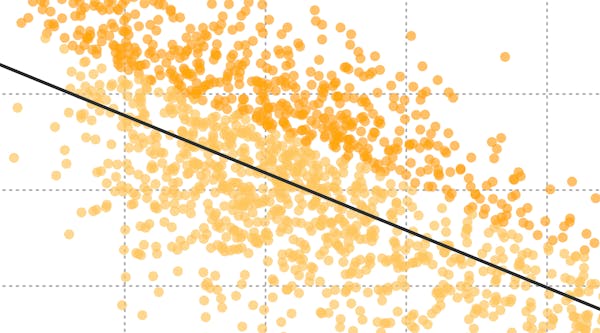

High-poverty schools like Gideon Pond are not often lauded for their math and reading proficiency scores because poverty is the main factor that explains the variation in scores from one school to another. Schools with the highest scores overall tend to have low poverty rates. But using a regression analysis to account for poverty, the Star Tribune found Gideon Pond is among the roughly 30% of high-poverty schools that did better than expected last year on the state's math test. It's also among the 20% that beat the odds on the reading exam.

The keys, educators and researchers say, are building connections to support families and constantly finding ways to introduce concepts into different kinds of lessons.

"We talk all the time about how everybody at Gideon Pond believes that relationships are key to our school," Principal Salma Hussein said.

The relationship building starts as soon as children enter kindergarten. Families become accustomed to having their children bring home a yellow folder called a Bee Book that details what they're learning and how they're doing in class — and gives parents a chance to respond. Educators say the constant communication — plus monthly open houses for Spanish- and Somali-speaking households — engenders community trust.

Throughout students' time at Gideon Pond, teachers also build lesson plans to get students acquainted with each other.

In the lower grades, students share what they did over the weekend and write cultural identity books. By fifth grade, teacher Jes Rau pushes her students to partner with classmates they haven't interacted with much in their first few years at the school.

On a recent morning, she paired students together to scour the room for sticky notes with short sentences written on them. Each duo was tasked with identifying whether the sentence was written in first-, second- or third-person perspective.

"They should be able to learn from each other," Rau said, adding that those exercises create community in the room.

Strategies for success

Chase Nordengren, principal research lead for effective instructional strategies at the Portland, Ore.-based Northwest Evaluation Association, said the strategies for classroom success fall into three categories: empowering students, exposing them to more content, and teachers optimizing their instructional time.

He wrote a report that details 10 strategies for high-performing classrooms after observing a school in Illinois during the 2022-23 academic year.

Among his suggestions? Having teachers mix whole-group and small group instruction throughout their lessons, and adjusting their plans on the fly as they assess student needs. He also suggests educators incorporate takeaways for different subject areas in each lesson.

"The strategies are really looking at how to understand that a teacher can't be in 35 places at once," he said. "How do you maximize their time?"

That might be introducing math terms during vocabulary lessons or having students write essays about their lives to share with classmates, strategies employed by Gideon Pond educators.

Still, Nordengren acknowledges that schools must cope with the external pressures students bring into them.

In 2022, a family of four qualified for free school meals if their household income was less than $51,338, according to federal guidelines. That makes life difficult when rents hover around $1,300 a month in the Twin Cities and inflation has eaten away at household budgets over the last few years.

Anxiety has also increased among adults and children alike over the last decade, exacerbated by the stresses of the pandemic. Those external pressures eventually seep into the classroom.

"Are we giving them the kinds of supports they need to give them the best chance possible?" Nordengren said.

Connections to school

The first-graders Terese Trekell teaches at Gideon Pond are young enough that they haven't had their education interrupted by stay-home orders or quarantines. But some of their siblings have. And their parents may be feeling the financial pressures of the last few years. Those stressors seep into the classroom.

"It's our job to make sure they have what they need when they're in our care," Trekell said.

Sometimes that even means sending children home with a bit of extra food and some school supplies. At Gideon Pond, educators call the initiative "brainpower in a backpack."

Seventy miles away in Buffalo Lake near Hutchinson, teachers and local community organizers call it "pack the back."

The local elementary school, which also draws students from the neighboring communities of Hector and Stewart, enrolled 468 students during the 2022-23 school year, according to state figures. Sixty percent qualify for free school meals. Their math and reading scores last year were about double what would be expected considering the school's poverty level.

Jody Weis, who teaches third grade and chairs Buffalo Lake-Hector Elementary School's math committee, said educators there have found success in providing students with weekend care packages. Those include snacks and games families can play together, plus math worksheets that parents could help their children with.

"Our intention for the at-home piece is that we felt like families weren't getting that opportunity to engage as much as they wanted to," Weis said.

Parents raved about the packets. And when fourth-grade teacher Melanie Rudeen, who chairs the school's literacy committee, saw many students struggle in that subject, she also began sending small reading and writing lessons home.

"That's been a very good thing that we've implemented with our entire K-5 grades," Rudeen said of the packets. "We have a lot of kiddos, and it's an awesome opportunity to have them keep that connection to school."

Want to share info with the Star Tribune? How to do it securely

'Safe recovery sites' would offer syringes, naloxone and more to people using drugs. The plan could be in peril.

New Minnesota GOP leaders seek peace with party's anti-establishment wing

Who is Republican Lisa Demuth, Minnesota's first House speaker of color?