Homeless encampments aren't a new Twin Cities phenomenon. But the latest ones are different.

Listen and subscribe to our podcast: Via Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Stitcher

Homelessness has lately become one of the most visible and controversial public policy issues in the Twin Cities.

It is not unusual to see tent-filled encampments spring up overnight in pockets of the urban core, only to be removed days or weeks later by law enforcement. Local leaders say the camps are unsafe, but residents say living this way is their only option.

Reader Edward Hauser of Becker sought some historical perspective about this problem. He recalled his grandparents talking about "bums" riding the rails during the Great Depression, but doesn't recall encampments being much of an issue until now.

"Where did homeless people go or live in the past?" Hauser asked Curious Minnesota, the Star Tribune's community reporting project fueled by reader questions. "I know they must have existed."

Though rocked by different hardships throughout history, deeply poor Americans have always lived rough in public areas. Encampments by different names have existed in Minnesota since the state's early history, according to research and newspaper accounts on the subject located with the assistance of Hennepin County Library staff.

In the 1880s — predating city codes that set standards for human habitation — European immigrants inhabited barrios cobbled from scrap building materials on the Mississippi River flats. Then came the "Hoovertowns" and "Rooseveltvilles" of the 1930s and a skid row that sprawled across downtown Minneapolis for the first half of the 20th century.

Time and again, authorities razed homes of last resort in the name of safety and removing urban blight.

But those fighting homelessness today say the magnitude and complexity of contemporary encampments surpass anything that existed in recent memory. In addition to an affordable housing shortage, factors driving more people to live on the streets include the availability of cheap and powerful opioids — which has complicated efforts to get people stable housing.

Refuges on the river

America has grappled with homelessness since at least the colonial era, when people showed less sympathy toward the issue than they do today, according to the 1989 book "Down and Out in America: the Origins of Homelessness." Author Peter Rossi documented 17th century New England town meetings in which widows, children, disabled and elderly people were barred from settlement rights and public assistance, forcing them to join the ranks of a transient poor.

Beginning in 1860, Minneapolis and St. Paul relegated their newest and poorest immigrants to creek- and riverside shanties that flooded each spring, including the West Side Flats, Swede Hollow and the Bohemian Flats. Notorious for crime and poor sanitation, these types of settlements would not be permitted today.

Yet many families who built their homes in the Mississippi floodplain stayed for decades until private developers bought out the land or the city forcibly ejected them.

"Wives hold river flat homes when police attempt eviction," blared the headline of a 1923 Minneapolis Morning Tribune story about "an angry group of women" defending their homes in the Bohemian Flats.

Most of the "squatters" were evicted from 1926 to 1931. Archaeologist Rachel Hines traced nearly 40% of the ejected households to new addresses by 1930, but many others could not be found in the city directory.

Some may have moved away from Minneapolis or changed the spelling of their names, said Hines, who wrote about the issue for the University of Minnesota's Open Rivers journal. But the high number of people who went missing "may indicate they had nowhere to go when they left the flats."

In 1933, unemployed men showed reporters how they kept warm with rudimentary brick stoves in a camp called "Rooseveltville-on-the-Mississippi." The following year, city crews and police burned the shack village to the ground.

"Just what happened to the several score homeless men who dwelt along the bank through the cold of winter and the heat of summer, no one knows. Maybe some of them have jobs. Maybe some have moved to other — and more exclusive — 'suburbs' of the city," wrote the Minneapolis Tribune, implying the existence of more hidden camps.

In 1938, a 20-man community dubbed "Depression Street, Hoovertown" was living on the banks of the Mississippi River in "flimsy, low one-room shanties." A Minneapolis Tribune article about the encampment said the men would hunker down inside for days in the brutal cold, and scavenge nearby junk piles to earn money for food.

Downtown becomes Skid Row

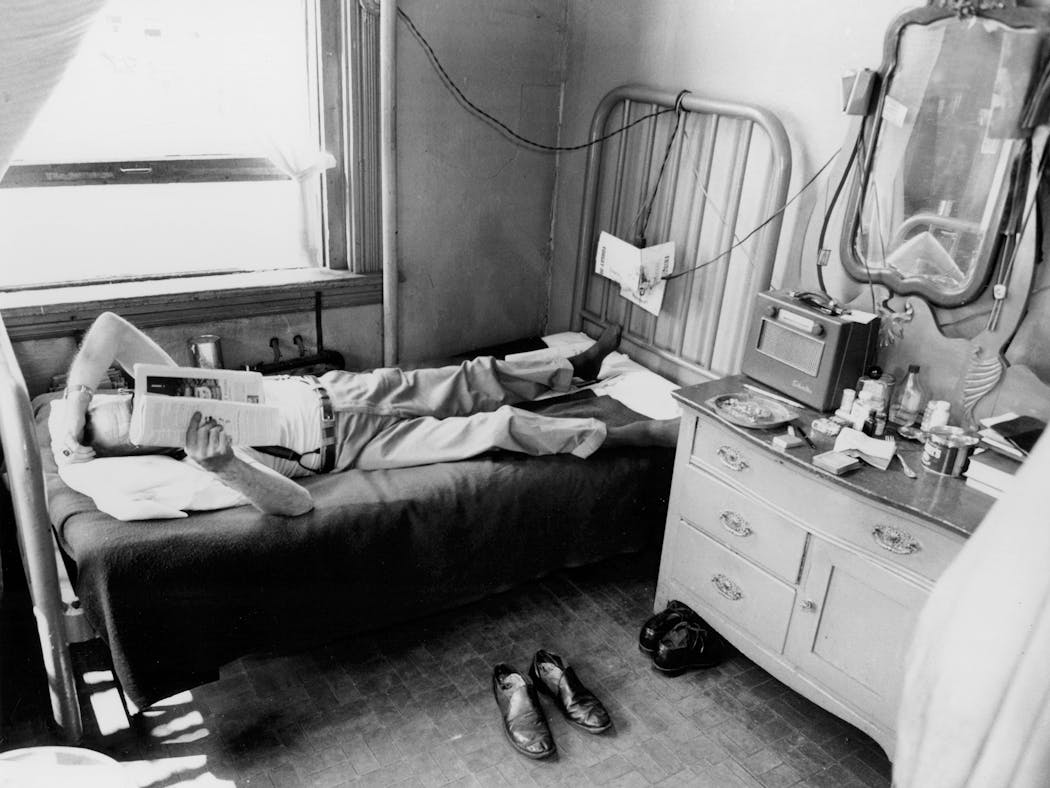

Concurrently, downtown Minneapolis developed into a catch basin for the very poor and seasonally employed — full of the "cage hotels" where they lived and the saloons where they drank. While not technically homeless, the day laborers and sex workers of the Gateway District's "Skid Row" were right on the edge, treated as the undesirables of the 1920s-1960s and constantly being arrested.

Some help came in the form of the Salvation Army and Union City Mission — the area's earliest food and shelter depots.

"However, if a man did not give evidence of wanting to be 'saved,' he had to move on in the morning," wrote Keith Arthur Lovald in his 1960 dissertation, "From Hobohemia to Skid Row, the Changing Community of the Homeless Man."

In the early 1960s, with Skid Row shouldering blame for suburban flight and the decline of the city, Minneapolis bulldozed the entire area.

There were more than 2,400 "permanent" residents of the neighborhood at the time, according to a 1963 Gateway District relocation report that Star Tribune editor James Eli Shiffer studied for his book, "The King of Skid Row." Nearly 600 moved away ahead of demolition — most to some unknown destination. Of those remaining, 70% found other rental housing, 9% went into institutional care and 3% died.

Minneapolis reduced thousands of single-occupancy boarding rooms to rubble because they were unsafe and substandard. But at least those structures kept roofs over heads, said Margaret Miles, who began her career with St. Stephen's Human Services in the 1990s and is writing a book on the history of homelessness in Minnesota.

"What you really have over time is the people who are vulnerable in any way in their life are going to be the last people who are thought of when cities and the nation thinks about housing needs," she said.

Modern encampments are more visible, complex

The roots of modern unsheltered homelessness date to the 1970s and 80s, when economic stagflation coincided with deinstitutionalization — the release of mentally ill people from restrictive state hospitals.

Many institutionalized people were rehoused in community-based group homes with the type of support they needed to live semi-autonomous lives. Others had to rely on new emergency homeless shelters with limited capacity.

This resulted in many people with disabilities living on the street by the early 1990s, according to research by the Wilder Foundation, which has studied the issue ever since.

Homeless encampments existed in the intervening decades, but they were hidden near the river or scattered between bridges and grassy traffic refuges — like "Suicide Hill" in Loring Park.

The larger encampments that have become commonplace today began springing up in 2018, with the Wall of the Forgotten Natives in Minneapolis and another at Cathedral Hill in St. Paul. That year, the Wilder study found an alarming 62% increase in the number of people living outdoors in Minnesota's cold.

Occupants at the time said they lived in the encampments because of the rising cost of living, lack of space in emergency shelters and the closure of smaller encampments. They said larger homeless encampments gave them a sense of semi-permanency, safety in numbers and concentrated resources — despite also being targeted by heroin dealers.

Powerful new drugs are complicating efforts to get people into more permanent housing. Officials are very concerned about the strength and cheapness of fentanyl as well as its increasingly popular mixer xylazine, a non-opioid sedative whose effects cannot be reversed by the life-saving medication naloxone.

Fentanyl is one of the most significant issues that Cathy ten Broeke has seen in her three-decade career focused on ending homelessness. The executive director for the Minnesota Interagency Council on Homelessness, ten Broeke said she cannot remember another drug epidemic colliding with an explosion in homelessness the way it has in recent years.

To meet the moment, the Minnesota Legislature passed a $1 billion package that funds affordable housing, helps people pay rent and offsets down payment costs. A nationwide opioid settlement has also given counties and cities funds to tackle the issue, like providing treatment for expectant parents who would then be in a better position to keep their homes and children.

"It's so much more complex, the situations that people are finding themselves in on the street now," ten Broeke said. "The challenges that people are facing makes access to housing even more difficult, and it's more visible."

If you'd like to submit a Curious Minnesota question, fill out the form below:

Read more Curious Minnesota stories:

How did early settlers survive their first Minnesota winters?

Is it legal to panhandle in the median of Minneapolis streets?

How did the North Loop in Minneapolis get its name?

Why do Minnesotans have accents?

What was life like in Minnesota during the flu pandemic of 1918?

Was the Minneapolis Park Board created to benefit wealthy land owners?